By Daniel Dunaief

Cancer acts as a thief, robbing people of time, energy, and quality of life. In the end, cancer can trigger the painful wasting condition known as cachexia, in which a beloved relative, friend or neighbor loses far too much weight, leaving them in an emaciated, weakened condition.

A team of researchers at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory has been studying various triggers and mechanisms involved in cachexia, hoping to find the signals that enable this process.

Recently, CSHL scientists collaborated on a discovery published in the journal Nature Communications that connected a molecule called interleukin-6, or IL-6, to the area postrema in the brain, triggering cachexia.

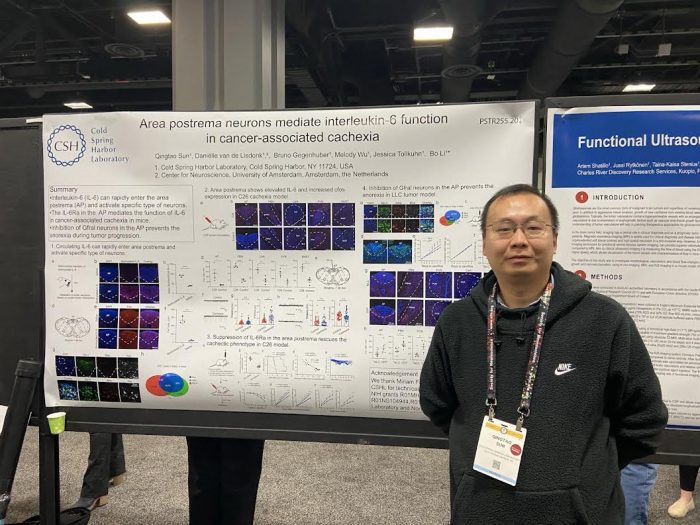

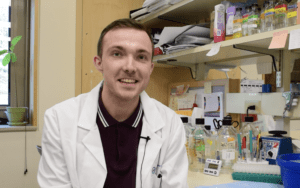

By deleting the receptors in this part of the brain for IL-6, “we can prevent animals from developing cachexia,” said Qingtao Sun, a postdoctoral researcher in the laboratory of Professor Bo Li.

Through additional experiments, scientists hope to build on this discovery to develop new therapeutic treatments when doctors have no current remedy for a condition that is often the cause of death for people who develop cancer.

To be sure, the promising research results at this point have been in an animal model. Any new treatment for people would not only require additional research, but would also need to minimize the potential side effects of reducing IL-6.

Like so many other molecules in the body, IL-6 plays an important role in a healthy system, promoting anti- and pro-inflammatory responses among immune cells, which can help fight off infections and even prevent cancer.

“Our study suggests we need to specifically target IL-6 or its receptors only in the area prostrema,” explained Li in an email.

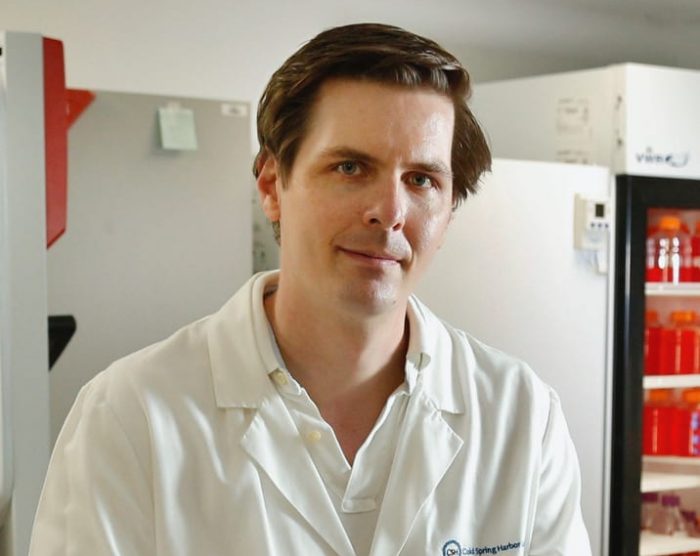

Tobias Janowitz, Associate Professor at CSHL and a collaborator on this project, recognized that balancing therapeutic effects with potential side effects is a “big challenge in general and also is here.”

Additionally, Li added that it is possible that the progression of cachexia could involve other mechanistic steps in humans, which could mean reducing IL-6 alone might not be sufficient to slow or stop this process.

“Cachexia is the consequence of multi-organ interactions and progressive changes, so the underlying mechanisms have to be multifactorial, too,” Miriam Ferrer Gonzalez, a co-first author and former PhD student in Janowitz’s lab, explained in an email.

Nonetheless, this research result offers a promising potential target to develop future stand alone or cocktail treatments.

The power of collaborations

Working in a neuroscience lab, Sun explained that this discovery depended on several collaborations throughout Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

“This progress wouldn’t be possible if it’s only done in our own lab,” said Sun. “We are a neuroscience lab. Before this study, we mainly focused on how the brain works. We have no experience in studying cachexia.”

This paper is the first in Li’s lab that studied cachexia. Before Li’s postdoc started this project, Sun had focused on how the brain works and had no experience with cachexia.

When Sun first joined Li’s lab three years ago, Li asked his postdoctoral researcher to conduct an experiment to see whether circulating IL-6 could enter the brain and, if so where.

Sun discovered that it could only enter one area, which took Li’s research “in an exciting direction,” Li said.

CSHL Collaborators included Janowitz, Ferrer Gonzalez, Associate Professor Jessica Tolkhun, and Cancer Center Director David Tuveson and former CSHL Professor and current Principal Investigator in Neurobiology at Duke University School of Medicine Z. Josh Huang.

Tollkuhn’s lab provided the genetic tool to help delete the IL-6 receptor.

The combination of expertise is “what made this collaboration a success,” Ferrer Gonzalez, who is now Program Manager for the Weill Cornell Medicine partnership with the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, explained in an email.

Tuveson added that pancreatic cancer is often accompanied by severe cachexia.

“Identifying a specific area in the brain that participates in sensing IL-6 levels is fascinating as it suggests new ways to understand physiological responses to elevated inflammation and to intervene to blunt this response,” Tuveson explained. “Work in the field supports the concept that slowing or reversing cachexia would improve the fitness of cancer patients to thereby improve the quality and quantity of life and enable therapeutic interventions to proceed.”

Tuveson described his lab’s role as “modest” in promoting this research program by providing cancer model systems and advising senior authors Li and Janowitz.

Co-leading an effort to develop new treatments for cachexia that received a $25 million grant from the Cancer Grand Challenge, Janowitz helped Sun understand the processes involved in the wasting disease.

Connecting the tumor biology to the brain is an “important step” for cachexia research, Janowitz added. He believes this step is likely not the only causative process for cachexia.

Cutting the signal

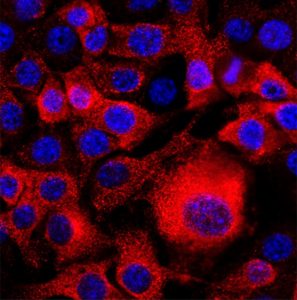

After discovering that IL-6 affected the brain in the area postrema, Sun sought to determine its relevance in the context of cachexia.

After he deleted receptors for this molecule, the survival period for the test animals was double that for those who had interleukin 6 receptors in this part of the brain. Some of the test animals still died of cachexia, which Sun suggested may be due to technical issues. The virus they used may not have affected enough neurons in the area postrema.

In the Nature Communications research, Sun studied cachexia for colon cancer, lung cancer and pancreatic cancer.

Sun expects that he will look at cancer models for other types of the disease as well.

“In the future, we will probably focus on different types” of cancer, he added.

Long journey

Born and raised in Henan province in the town of Weihui, China, Sun currently lives in Syosset. When he’s not in the lab, he enjoyed playing basketball and fishing for flounder.

When he was growing up, he showed a particular interest in science.

As for the next steps in the research, Sun is collaborating with other labs to develop new strategies to treat cancer cachexia.

He is eager to contribute to efforts that will lead to future remedies for cachexia.

“We are trying to develop some therapeutic treatment,” Sun said.