By Daniel Dunaief

It started over four decades ago, with a “help wanted” advertisement.

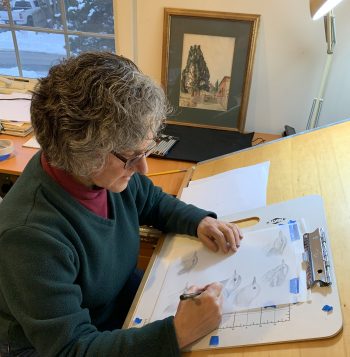

Luci Betti-Nash needed money for art supplies. She answered an ad from the Stony Brook University Department of Anatomical Sciences that sought artists who could draw bones. She found the work interesting and realized that she could “do it fairly easily. I could not have imagined a more fulfilling career.”

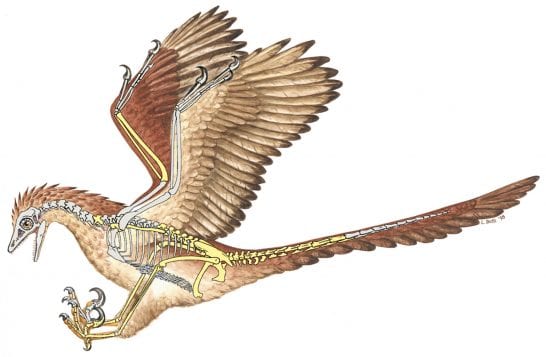

Betti-Nash spent 41 years responding to requests to provide illustrations for a wide range of scientific papers, contributing images that became a part of charts and graphs and drawing everything from single-celled organisms to dinosaurs. She retired last April.

Her coworkers at Stony Brook, many of whom collaborated with her for decades, appreciated her contributions and her passion and precision for her job.

Maureen O’Leary, Professor in the Department of Anatomical Sciences, said Betti-Nash’s work enhanced her professional efforts. “I couldn’t have had the same career without her,” O’Leary wrote in an email. “Artists are true partners.”

O’Leary appreciated how Betti-Nash noticed parts of the work that scientists miss.

“I think the most important thing is figuring out together what to put in and what to leave out of a figure,” O’Leary explained. “A photograph shows everything and it can be a blizzard of detail, really too much, and it will not focus the eye. The artist-scientist collaboration is about simplifying the detail to show what is important and how to show it clearly.”

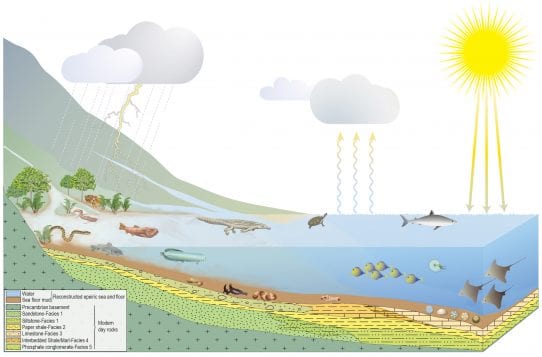

One of O’Leary’s favorite illustrations from Betti-Nash was a pull-out, color figure that envisioned the ancient Trans-Saharan Seaway from about 75 million years ago. The shallow sea, which was described in the movie “Aquaman,” supported numerous species that are currently extinct. Betti-Nash created a figure that showed these creatures in the sea and how water drained from nearby mountains, all superimposed over the geology.

“It told the story of how ancient life turned into rocks and fossils,” O’Leary explained.

Betti-Nash, who continues to sketch from her home office and plans to be selective about taking on future assignments, has numerous stories to tell about her work.

For starters, the world of science is rife with jargon. When she was starting out, she didn’t always stop researchers who tossed around the terms that populate their life as if they were a part of everyone’s vocabulary.

“Some [scientists] would come in and assume you knew exactly what they were talking about,” Betti-Nash said. “It was something they were studying for years. They would assume you knew all the terminology.”

Each discipline, from cell biology to gross anatomy to dinosaur taxonomy had its own terminology, some of which “was way over my head,” she said.

Early in her career, Betti-Nash felt she didn’t know details she thought she should.

“The older I got, the bolder I got about asking” scientists to explain what they meant in terms she could understand, she said, adding that she felt fortunate to have scientists who were “more than willing and eager to answer my questions when I was bold enough to ask. That was one of the many life lessons I learned … don’t be afraid to ask questions.”

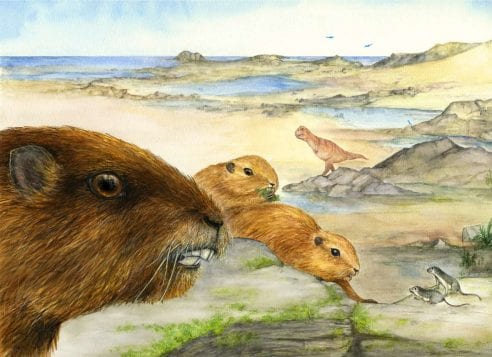

Betti-Nash sometimes had to work under intense time pressure. Collaborating with David Krause, who was at Stony Brook and is now Senior Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology in the Department of Earth Sciences at the Denver Museum of Science, Betti-Nash illustrated the largest frog ever discovered, which lived in Madagascar over 65 million years ago. Called the Beelzebufo, this frog weighed in at a hefty 10 pounds and was 16 inches. Ribbit!

A short time before going to press, the scientific team decided they needed a common object as a frame of reference to compare the size of this ancient amphibian and the largest living frog in Madagascar.

“We scrambled,” Betti-Nash recalled. “We decided on a pencil.”

She didn’t have time to draw the pencil, so she put it on her scanner, did some quick painting in Photoshop, put a shadow in, added it to the scan of the painting, saved it in the format required for the journal and sent it off.

“Adding the pencil was one of those typical strokes of genius that [Betti-Nash] routinely added to artwork,” explained Krause in an email. “Everyone knows the size of a number 2 pencil.”

Even though she hadn’t sculpted in 32 years, she had to create a sculpture of the frog that students could touch. The sculpture had to be non-toxic, dry and ready within three days.

Betti-Nash turned to the Guild of Natural Science Illustrators, asking for help with ideas for the materials. She also asked Joseph Groenke from Krause’s lab to contribute his fossil preparing experience. She used an epoxy clay that she massaged into shape, and then colored it with acrylic, non-toxic paints.

That sculpture was featured as a part of a display at Stony Brook Hospital for years and has since traveled with Krause to Denver where “kids especially love it, in part because it is touchable,” Krause wrote.

Krause was grateful for a partnership with Betti-Nash that spanned almost 40 years.

“There is no doubt in my mind that [Betti-Nash] made me a better scientist and there is also no doubt that my science is better” because of her, he explained. Krause described her stipple drawings as “incredibly painstaking to execute.” His favorite is of a large fossil crocodile found in Madagascar from the Late Cretaceous called Mahajangasuchus.

Betti-Nash urges artists considering entering the field of scientific illustrating to attend graduate school or even to take undergraduate courses, which would provide time to learn skills and terminology before working in the field.

She also suggests artists remain “interested in what you’re drawing at that moment, no matter what it is,” she said, adding that drawing skills provide a solid foundation for a career in science illustrating. Computer skills, which help with animation and videos, are good tools to learn as well.

Growing up in Eastchester, Betti-Nash often found herself doodling patterns in her notebooks. When she worked on graph paper, she colored in the squares. She also received artistic guidance from her father, the late John Betti.

A graphic designer, Betti worked for a company in Westchester, where he designed the town seal for Tuckahoe as well as the small airplane wings children used to get when they flew on planes.

During World War II, Betti, who grew up in Corona, Queens, used his artistic skills to create three-dimensional models from aerial photographs. Stationed close to the residence of his extended family in Italy during part of the war, Betti also created watercolor paintings of the Italian landscape.

When she was growing up, Betti-Nash had the “best model-making teacher in my dad,” who taught her to create paper maché.

Married to fellow illustrator Stephen Nash, Betti-Nash plans to remain active as an artist, doing her own illustrations involving nature and the relationship between birds and the environment.

She currently leads Second Saturday Bird Walks at Avalon Nature Preserve in Stony Brook and Frank Melville Memorial Park in Setauket through the Four Harbors Audubon Society (4HAS.org)

Betti-Nash is pleased with a career that all started with a response to an ad in the paper. “I feel very privileged to have had the opportunity to work as a scientific illustrator,” she said. “I hope I was able to help communicate the science behind the discoveries that the amazing scientists at Stony Brook made during my time there.”

All photos courtesy of Luci Betti-Nash