By Daniel Dunaief

Henry Ford revolutionized the way people manufactured cars through automation, speeding up the process, reducing waste and cutting costs.

Similarly, at Brookhaven National Laboratory, researchers like the newly hired Young Jae Shin, who is a staff scientist at the Center for Functional Nanomaterials, hopes to improve the process of automating the handling of thin flakes of material used in a next generation technology called quantum information science, or QIS.

Working with scientists at Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Shin is looking for ways to handle these flakes, which are one atom thick, of two-dimensional layers from different materials. Stacked together, these flakes can help create structures with specific electronic, magnetic or optical properties that can be used as sensors, in communication, or encryption.

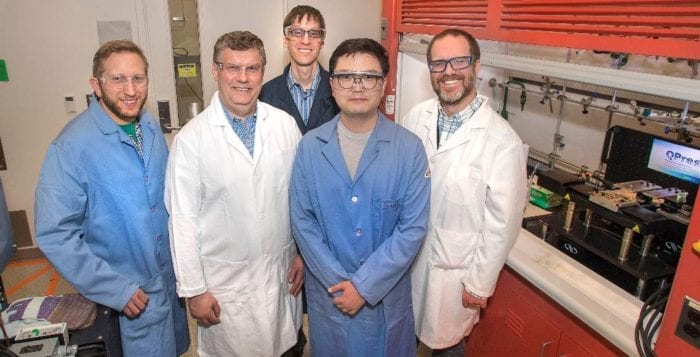

“Researchers are building these kinds of customized structures manually now,” explained Kevin Yager, leader of the CFN Electronic Nanomaterials Group, in an email. “QPress [Quantum Material Press] will allow us to automate this.” At this point, QPress is just starting, but, if it works, it will “absolutely allow us to accelerate the study of these materials, allowing researchers to find optimal materials quickly,” Yager continued.

Theoretically, quantum computers overcome the limitations of other systems, Shin explained.

The flakes come from the exfoliation of thin structures taken from a bulk material. This is akin to a collection of leaves that fall around trees. According to Yager, the structures scientists hope to make would be akin to a collection of leaves from different trees, put together to make a new structure or material with specific properties. “The idea is for the robot to sift through the flakes, and identify the ‘best’ ones and to stack these together into the right structure. The ‘stacking’ will involve combining flakes of different materials,” he said.

The less desirable flakes typically are the wrong size, have tears, ripples or other defects and have contaminants. Groups of scientists are predicting the kinds of layered designs that will have desired properties.

Shin suggested that the CFN supports the needs of the end user community, as CFN is a “user-based facility.”

Physicists at Harvard and MIT plan to use the QPress to study unusual forms of superconductivity. By tapping into materials that conduct electricity without losing energy at lower temperatures, researchers may make progress in quantum computing, which could exceed the ability of the current state-of-the-art supercomputers.

Stacking the flakes can create new materials whose properties not only depend on the individual layers, but also on the angle between the stacks. Scientists can change one of these new structures from having metallic to having insulating properties, just by altering the relative angle of the atoms. The challenge, however, is that putting these fine layers together by hand takes time and generates errors which, BNL hopes, an automated approach can help reduce.

“Ultimately, we would like to develop a robot that delivers a stacked structure based on the 2-D flake sequences and crystal orientations that scientists select through a web interface” to a machine, Charles Black, the head of the Center for Functional Nanomaterials at BNL, explained in a recent BNL feature. “If successful, the QPress would enable scientists to spend their time and energy studying materials, rather than making them.”

Barring unforeseen delays, scientists anticipate that they will be able to build a machine that creates these flakes, catalogs them, stacks them and characterizes their properties within three years. These functions will be available online in stages, to allow the use of the QPress prior to its completion.

Each stage in the QPress process uses computer software to reduce the effort involved in generating and interpreting usable structures.

Minh Hoai Nguyen, an assistant professor in the Department of Computer Science at Stony Brook University and doctoral student Boyu Wang from the Computer Vision Lab at SBU are creating a flake cataloger, which will use image analysis software to scan and record the location of flakes and their properties.

“The flakes that scientists are interested in are thin and thus faint, so manual and visual inspection is a laborious and error-prone process,” Nguyen said in the BNL feature.

At BNL, Shin is one of three scientists the Upton-based facility is hiring as a part of this effort. They are also seeking robot or imaging process experts. Shin has “been in the CFN just a short while, but is already having an impact- — for instance, allowing us to handle classes of two-dimensional materials that we were not working with before,” Yager said.

The field of quantum information science is extremely competitive, with researchers from all over the world seeking ways to benefit from the properties of materials on such a small scale. The United States has been investing in this field to develop leadership science in this area.

The University of Tokyo has developed an automation system, but Shin explained that it is still not perfect.

Yager said that numerous unknown applications are “waiting to be discovered. Researchers are working hard on real quantum computers. Prototypes already exist but creating viable large-scale quantum computers is a major challenge.”

A resident of on-site housing at BNL, Shin was born in the United States and grew up in Korea. He is married to Hyo Jung Kim, who is studying violin at Boston University.

As for the work Shin and others are doing, Yager suggested that the effort has generated considerable interest at the CFN.

“There is huge excitement at BNL about quantum research broadly and QPress in particular,” said Yager. Shin is “a big part of this — bringing new technical knowledge and new enthusiasm to this ambitious project.”