By Daniel Dunaief

While it’s easy to see and study materials in valleys or on the tops of bare mountains, it’s much more difficult to know what’s beneath 2.7 kilometers of ice. Turns out, that kind of question is much more than academic or hypothetical.

At the South Pole, glaciers sit on top of land that never sees the light of day, but that is relevant for the future of cities like Manhattan and Boston.

The solid land beneath glaciers has a strong effect on the movement of the ice sheet, which can impact the melting rate of the ice and sea level change.

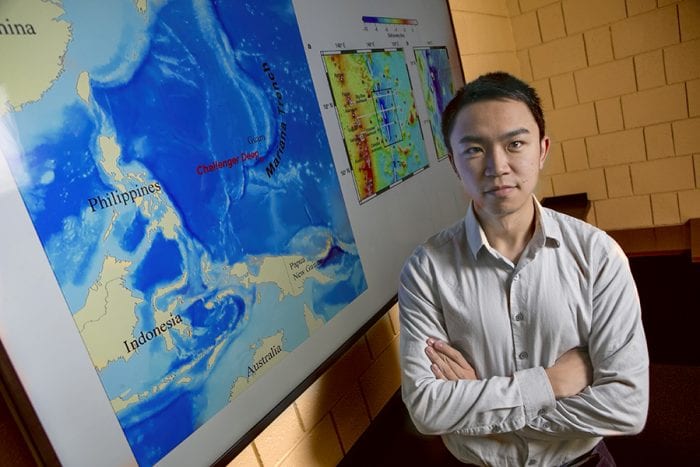

Weisen Shen, Assistant Professor in the Department of Geosciences at Stony Brook University, recently received over $625,000 over the course of five years from the National Science Foundation to study the unexplored land beneath the East Antarctic Ice Sheet at the South Pole.

The subglacial water and hydrosystems, together with geology such as sediment or hard rocks, affect the dynamics and contribute to the movement speed of the ice sheet.

Once Shen provides a better understanding of the material beneath the ice, including glacial water, he can follow that up with other researchers to interpret the implications of ice sheet dynamics.

“We can predict better what’s the contribution of the Antarctic ice sheet to the sea level change” which will offer modelers a way to gauge the likely impact of global warming in future decades, he said.

Using seismic data

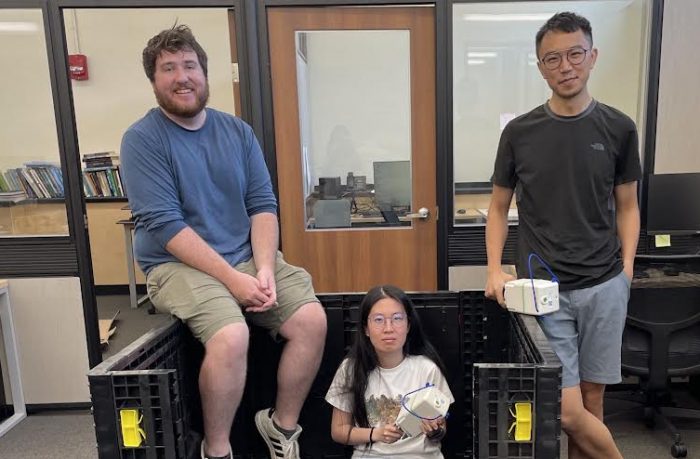

Starting this November, Shen and graduate students Siyuan Sui, Thomas Reilly and Hanxiao Wu will venture for two months to the South Pole with seismic monitors.

By placing 183 seismic nodes and installing an additional eight broad-band seismic stations, Shen and his team will quantify the seismic properties and, eventually, use them to infer the composition, density and temperature structure of the crust and the uppermost mantle.

The temperature when they place these monitors will be 10 to 30 degrees below 0 degrees Fahrenheit. They will need to do some digging as they deploy these sensors near the surface.

While the South Pole is believed to be geologically stable, signs of sub-glacial melting suggest the crust may bear a higher concentration of highly radioactive elements such as uranium, thorium and potassium.

Those natural elements “produce heat all the time,” said Shen.

The process and analysis of seismic waves works in the same way it would for the study of a prism. Looking at the refraction of light that enters and leaves the prism from various angles can help researchers differentiate light with different frequencies, revealing clues about the structure and composition of the prism.

Earth materials, meanwhile will also cause a differentiation in the speed of surface waves according to their frequencies. The differentiation in speeds is called “dispersion,” which Shen and his team will use to quantify the seismic properties. The area has enough natural waves that Shen won’t need to generate any man-made energy waves.

“We are carefully monitoring how fast [the seismic energy] travels” to determine the temperature, density and rock type, Shen said.

The water beneath the glacier can act like a slip ’n slide, making it easier for the glacier to move.

Some large lakes in Antarctica, such as Lake Vostok, have been mapped. The depth and contours of sub glacier lakes near the South Pole, however, are still unclear.

“We have to utilize a lot of different methods to study that,” said Shen.

The Stony Brook researcher will collaborate with colleagues to combine his seismic results with other types of data, such as radar, to cross examine the sub ice structures.

The work will involve three years of gathering field data and two years of analysis.

Educational component

In addition to gathering and analyzing data, Shen has added a significant educational component to the study. For the first time, he is bringing along Brentwood High School science teacher Dr. Rebecca Grella, A PhD graduate from Stony Brook University’s Ecology and Evolutionary Biology program, Grella will provide lectures and classes remotely from the field.

In addition to bringing a high school teacher, Shen will fund graduate students at Stony Brook who can help Brentwood students prepare for the Earth Science regents exam.

Shen is working with Kamazima Lwiza, Associate Professor in the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook, to bring Earth Science, including polar science, to schools in New York City and on Long Island with a bus equipped with mobile labs.

Lwiza, who is the Principal Investigator on the EarthBUS project, will work together with Shen to build a course module that includes a 45-minute lecture and exhibition.

Shen feels that the project will help him prepare to better educate students in graduate school, college, and K-12 in the community.

He feels a strong need to help K-12 students in particular with Earth Science.

As for students outside Brentwood, Shen said he has an open door policy in which the lab is receptive to high school and undergraduate students who would like to participate in his research all year long.

Once he collects the first batch of data from the upcoming trip to the South Pole, he will have to do considerable data processing, analysis and interpretation.

While Shen is looking forward to the upcoming field season, he knows he will miss time in his Stony Brook home with his wife Jiayi Xie, and his four-and-a-half year old son Luke and his 1.5 year old son Kai.

“It’s a huge burden for my wife,” Shen said, whose wife is working full time. When he returns, he “hopes to make it up to them.”

Shen believes, however, that the work he is doing is important in the bigger picture, including for his children.

Record high temperatures, which are occurring in the United States and elsewhere this summer, will “definitely have an impact on the dynamics of the ice sheet.” At the same time, the Antarctic ice sheet is at a record low.

“This is concerning and makes [it] more urgent to finish our work there,” he added.