By Daniel Dunaief

It’s not exactly a symphony, with varying sounds, tones, cadences and resonances all working together to take the listener on an auditory journey through colors, moods and meaning. In fact, the total length of the distortion is so short — about 0.1 seconds — that it’s a true scratch-your-ear-and-you’ll-miss-it moment.

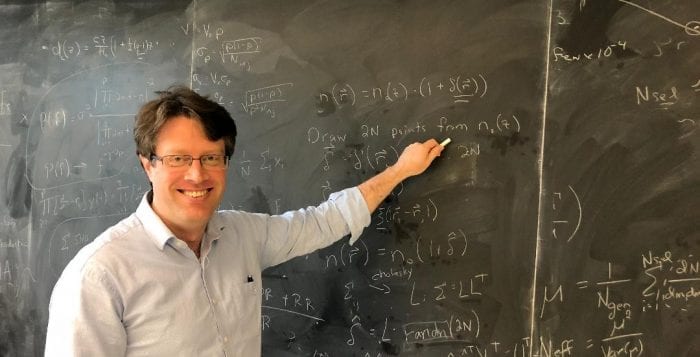

And yet, astrophysicists like William Farr, an associate professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Stony Brook University and a group leader in gravitational wave astronomy with the Simons Foundation Flatiron Institute, are thrilled that they have been able to measure distortions in space and time that occur at audio frequencies that they can convert into sounds. These distortions were made millions or even billions of years ago from merging black holes.

Farr, in collaboration with a team of scientists from various institutions, recently published a paper in Physical Review Letters on the topic.

While the ability to detect sounds sent hurtling through space billions of years before Tyrannosaurus Rex stalked its prey on Earth with its mammoth jaw and short forelimbs offers some excitement in and of itself, Farr and other scientists are intrigued by the implications for basic physical principles.

General relativity, a theory proposed by Albert Einstein over 100 years ago, offers specific predictions about gravitational waves traveling through space.“The big excitement is that we checked those predictions and they matched what we saw. It’s a very direct test of general relativity and its predictions about a super extreme environment near a black hole,” said Farr. There are other tests of general relativity, but none that directly test its predictions so close to the event horizon of a black hole, he explained.

General relativity predicts a spectrum of tones from a black hole, much like quantum mechanics predicts a spectrum line from a hydrogen atom, Farr explained.

The result of this analysis “provides another striking confirmation of the theory of general relativity and also demonstrates that there are even more exciting things that can be done with gravitational wave astrophysics,” Marilena Loverde, an assistant professor of physics at the C. N. Yang Institute for Theoretical Physics at Stony Brook University, explained in an email. Loverde suggested that Farr is “particularly well-known for bringing powerful new statistical techniques to extract science from vast astrophysical data sets.”

Farr and his colleagues discovered two distortions that they converted into tones from one merger event. By measuring the frequency of the first one, they could predict the frequency for all the other tones generated in the event. They detected one more event, whose frequency and decay rate were consistent with general relativity given the accuracy of the measurement.

So, what does the merger of two black holes sound like, from billions of light years away? Farr suggested it was like a “thunk” sent over that tremendous distance. The pitch of that sound varies depending on the masses of the black holes. The difference in sound is akin to the noise a bear makes compared with a chipmunk: A larger black hole, or animal, in this comparison, makes a noise with a deeper pitch.

He used data from the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO, which is a twin system located in Livingston, Louisiana, and Hanford, Washington. LIGO had collected data from black hole merger events over a noncontinuous six-month period from 2015 to 2017.

Farr chose the loudest one, which came from 1.5 billion years ago. Farr was using data from the instrument, which collects gravitational waves as they reach the two different locations, when it was less sensitive. Given the original data, he might not have discovered anything. He was, however, delighted to discover the first tone.

If something that far away emitted a gravitational wave sound that lasts such a short period of time, how, then, could the LIGO team and Farr’s analysis be sure the sound originated with the cosmic collision?

“We make ‘extreme’ efforts to be sure about this,” Farr explained in an email. “It is one reason we built two instruments (so that something weird happening in one does not fool us).” He said he makes sure the signal is consistently recorded in both concurrently. To rule out distortions that might come from other events, like comets slamming into exoplanets, he can measure the frequency of the event and its amplitude.

Black holes form when stars collapse. After the star that, in this case, was likely around 25 times the mass of the sun, exploded, what was left behind had an enormous mass. When another, nearby star becomes a black hole, the two black holes develop an orbit like their progenitor stars. When these stars become black holes, they will emit enough gravitational waves to shrink the orbit, leading to a merger over a few billion years. That’s what he “heard” from the last second or fraction of a second.

Farr expects to have the chance to analyze considerably more data over the next few months. First, he is working to analyze data that has already been released and then he will explore data from this year’s observations, which includes about 25 more mergers.

“The detectors are getting more sensitive,” he said. This year, scientists can see about 30 percent further than they could in the first and second observing runs, which translates into seeing over twice the total volume.

Farr has been at Stony Brook for almost a year. Prior to his arrival, he had lived in England for five years. He and his wife, Rachel, who have a 3½-year-old daughter, Katherine, live in Stony Brook.

As for his work, Farr is thrilled that he will have a chance to study more of these black hole merger sounds that, while not exactly Mozart, are, nonetheless, music to his ears. “Each different event tells us different things about how stars form and evolve,” he said.