By Daniel Dunaief

Despite the pause New York and so many other states are taking to combat the coronavirus, the awards can, and will, go on.

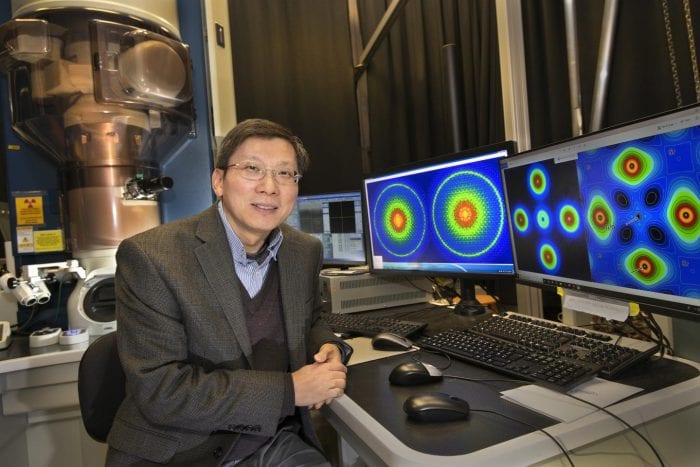

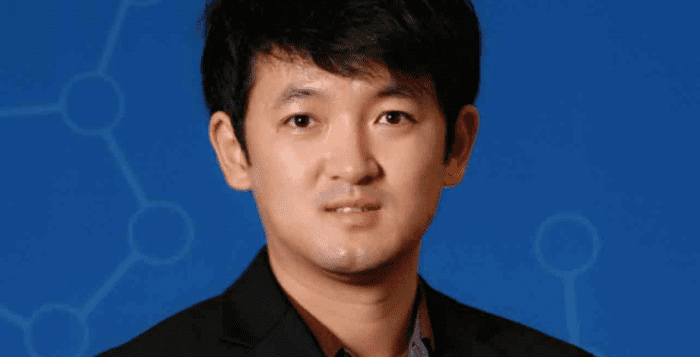

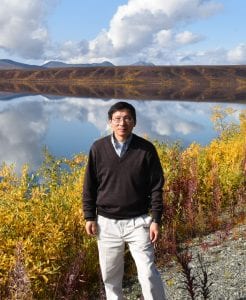

The Microscopy Society of America gave Brookhaven National Laboratory’s Lijun Wu the 2020 Chuck Fiori Award. The Award, which started in 1993, recognizes the achievements of a technologist in the physical sciences who has made long-standing contributions in microscopy or microanalysis.

Wu is the second consecutive BNL staff member to win the Chuck Fiori award. Dmitri Zakharov took home the honors last year.

Wu is an engineer in the Electron Microscopy and Nanostructure Group in the Condensed Matter Physics and Materials Science Division. He works with transmission electron microscopy in quantum materials, batteries, catalysts, and other energy materials. Wu learned how to write software programs on his own. His first effort in this area involved a program that indexed electron diffraction patterns. He has also created programs for simulating microscopy images and diffraction patterns.

Wu, who is hoping to pick up the award at the Microscopy Society of America meeting in August if the meeting still takes place, said he was “excited” to receive this distinction and was pleased for the support throughout his career at BNL.

Wu “has made significant contributions to the field of electron microscopy, especially quantitative electron diffraction,” group leader and senior scientist Yimei Zhu, said in a statement. “Applying his expertise in the field and talents in computer programming, [he] has advanced electron microscopy for material characterization. He well deserves the award.”

One of the most important contributions Wu, who has been at BNL since 1996, has made was in developing an electron diffraction method for measuring valence electron distribution. The valence electrons are the ones in the outermost shell of any substance or material.

Wu worked with Zhu and Johan Taftø, a visiting scientist from the University of Oslo, to develop an electron diffraction–based method for measuring valence electron distribution.

He appreciates the support and encouragement he has received from Zhu since he arrived at BNL.

Transmission electron microscopes can provide atomic-resolution images and electron-energy loss spectroscopy, Wu suggested. Through this work, scientists can determine where atoms are and what kind of atoms are present.

He would like to measure the distribution of these valence electrons through a process called quantitative electron diffraction.

By understanding how atoms share or transfer electrons, researchers can determine the physical properties of materials. Electron diffraction measurements can describe valence electron distribution from the bonds among atoms.

Wu and his colleagues developed a method called parallel recording of dark-field images. Through this technique, the scientists focus a beam above the sample they are studying and record numerous reflections from the same area. This is like studying the partial reflection of objects visible in windows on a city street and putting together a composite, three-dimensional view. Instead of cars, people, traffic lights and dog walkers, though, Wu and his colleagues are studying the distribution of electrons.

The information the scientists collect allows them to measure the charge transfer and aspherical valence electron distribution, which they need to describe electron orbitals for objects like high-temperature superconductors.

Using an electron probe, the team developed the technique to measure the displacement of atoms in crystal lattices with one-thousandth-of-a-nanometer accuracy.

To learn how to write software, Wu used several resources.

“I used literature and read books for computer programming,” he said. “I spent many, many years” learning how to write programs that would be useful in his research. He also consulted with colleagues, who have written similar programs.

Wu explained that the calculations necessary for his work far exceeded the functionality of a calculator. He also needed a super computer to handle the amount of data he was generating and the types of calculations necessary.

“If we used the older computer technique, it would take days or weeks to get one result,” he said.

A native of Pingjing in Hunan Province in China, Wu said learning English was considerably more challenging than understanding computer programming.

The youngest of nine siblings, Wu is the only one in the family who attended college. When he began his studies at the prestigious Shanghai Jiao Tong University, he said he was interested in physics and computers.

The college, however, decided his major, which was materials science.“They assigned it to me,” Wu said. “I liked it.”

He and his wife Jiangyan Fang, who is an accountant, have a 25-year-old son David, who lives in Boston and works with computers.

Wu, who started out at BNL as a Visiting Scientist, said he is comfortable living on Long Island. He said Long Island is cooler than his home town in the middle of China, where it’s generally hotter and more humid. For a week or two each year, the temperature can climb above 104 degrees Fahrenheit.

As for his work, Wu said he looks at the atomic level of substances. His techniques can explore how a defect in something like a battery affects how ions, like lithium, get in and through that.

“When you charge or discharge a battery, [I consider] how an electron gets through a defect. I always think about it this way.”

Wu has been working with Zhu and visiting scientist Qingping Meng from Shanghai Jiao Tong University, where Wu earned his Bachelor’s of Science and his Master’s in Science, on an initiative that advances the ability to determine valence electron distribution.

Wu is preparing a new publication. “I’m writing the manuscript and will introduce the method we are developing,” he said.