By Daniel Dunaief

The canary in the Arctic coal mines, chinstrap penguins need more ice. These multitudinous flightless birds also depend on the survival and abundance of the krill that feed on the plankton that live under the ice.

With global warming causing the volume of ice in the Antarctic to decline precipitously, the krill that form the majority of the diet of the chinstrap penguin have either declined or shifted their distribution further south, which has put pressure on the chinstrap penguins.

Indeed, at the end of December, a team of three graduate students (PhD students in Ecology and Evolution Alex Borowicz and Michael Wethington and MS student in Marine Science Noah Strycker) from the lab of Heather Lynch, who recently was promoted to the inaugural IACS Endowed Chair of Ecology & Evolution at Stony Brook University, joined Greenpeace on a five week mission to the Antarctic to catalog, for the first time in about 50 years, the reduction in the number of this specific penguin species.

The group, which included private contractor Steve Forrest and two graduate students from Northeastern University, “saw a shocking 55 percent decline in the chinstrap on Elephant Island,” Lynch said. That drop is “commensurate with declines elsewhere on the peninsula.”

Elephant Island and Low Island were the targets for this expedition. The scientific team surveyed about 99 percent of Elephant Island, which was last visited by the Joint Services Expedition in 1970-1971.

The decline on Elephant Island is surprising given that the conditions in the area are close to the ideal conditions for chinstraps.

In some colonies in the Antarctic, the declines were as much as 80 percent to 90 percent, with several small chinstrap colonies disappearing entirely.

“We had hoped that Elephant Island would be spared,” Lynch said. “In fact, that’s not at all the case.”

While many indications suggest that global warming is affecting krill, the amount of fishing in the area could also have some impact. It’s difficult to determine how much fishing contributes to this reduction, Lynch said, because the scientists don’t have enough information to understand the magnitude of that contribution.

The chinstrap is a picky eater. The only place the bird breeds is the Antarctic peninsula, Elephant Island and places associated with the peninsula. The concern is that it has few alternatives if krill declines or shifts further south.

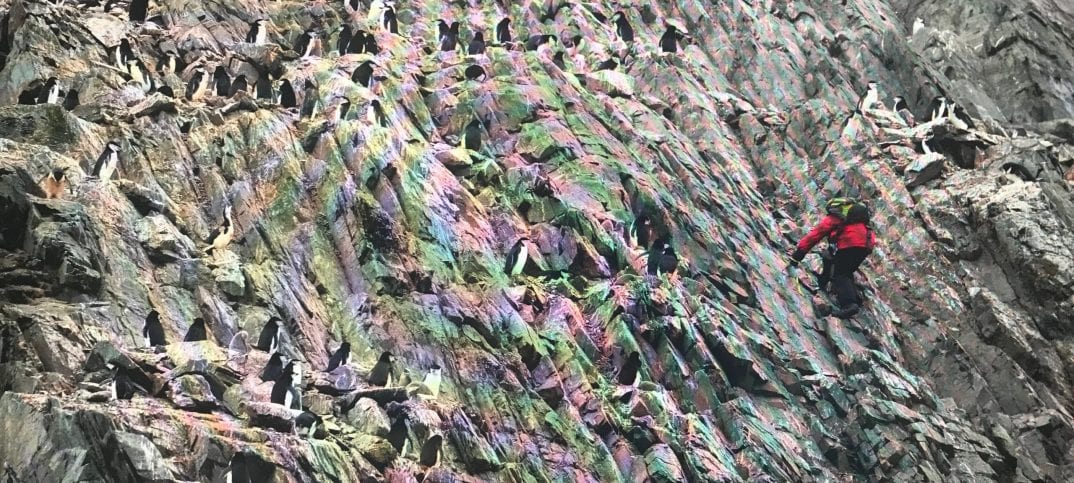

“Chinstraps have been under-studied in the last few decades, in part because so much attention has been focused on the other species and in part because they nest in such remote and challenging places,” Lynch explained in an email. “I hope our findings raise awareness of the chinstraps as being in serious trouble, and that will encourage everyone to help keep an eye on them.”

While these declines over 50 years is enormous, they don’t immediately put the flightless waterfowl that tends to mate with the same partner each year on the list of endangered species because millions of the sea birds that feel warm and soft to the touch are still waddling around the Antarctic.

Researchers believe that the biggest declines may have occurred in the 1980s and early 1990s, in part because areas with more regular monitoring showed reductions during those times.

Still, where there are more recent counts to use as a standard of comparison, the declines “show no signs of abating,” Lynch explained.

The evidence of warming in the Antarctic has been abundant this year. On Valentine’s Day, the Antarctic had its hottest day on record, reaching 69.35 degrees Fahrenheit. The high in Stony Brook that day was a much cooler 56 degrees.

“What’s more concerning is the long term trends in air temperature, which have been inching up steadily on the Antarctic Peninsula since at the least the 1940’s,” Lynch wrote in an email.

At the same time, other penguin species may be preparing to expand their range. King penguins started moving into the area several years ago, which represents a major range expansion. “It’s almost inevitable that they will eventually be able to raise chicks in this region,” Lynch suggested.

The northern part of the Antarctic is becoming much more like the sub Antarctic, which encourages other species to extend their range.

Among many other environmental and conservation organizations, Greenpeace is calling on the United Nation to protect 30 percent of the world’s oceans by 2030. The Antarctic was the last stop on a pole to pole cruise to raise awareness, Lynch said.

One of the many advantages of traveling with Greenpeace was that the ship was prepared to remove trash.

“We pulled up containers labeled poison,” Lynch said. Debris of all kinds had washed up on the hard-to-reach islands.

“People are not polluting the ocean in Antarctica, but pollution finds its way down there on a regular basis,” she added. “If people knew more about [the garbage and pollution that goes in the ocean], they’d be horrified. It is spoiling otherwise pristine places.”

Lynch appreciated that Greenpeace provided the opportunity to conduct scientific research without steering the results in any way or affecting her interpretation of the data.

“We were able to do our science unimpeded,” she said.

Counting penguins on the rocky islands required a combination of counting birds and nests in the more accessible areas and deploying drones in the areas that were harder to reach. One of Lynch’s partners Hanumant Singh, a Professor Mechanical and Industrial Engineering at Northeastern University, flew the drones over distant chinstrap colonies. The researchers launched the drones from land and from the small zodiac boats.

The next step in this research is to figure out where the penguins are going when they are not in the colony. “Using satellite tags to track penguins at sea is something I’d like to get into over the next few years, as it will answer some big questions for us about where penguins, including chinstraps, are trying to find food,” Lynch said.