By Daniel Dunaief

Diversity has become a buzz word in the workplace, as companies look to bring different perspectives that might represent customers, constituents or business partners. The same holds true for the human brain, which contains a wide assortment of interneurons that have numerous shapes and functions.

Interneurons act like a negative signal or a brake, slowing or stopping the transmission. Like a negative sign in math, though, some interneurons put the brakes on other neurons, performing a double negative role of disinhibiting. These cells of the nervous system, which are in places including the brain, spinal chord and retina, allow for the orderly and coordinated flow of signals.

One of the challenges in the study of these important cells is that scientists can’t agree on the number of types of interneurons.

“In classifying interneurons, everyone argues about them,” said Megan Crow, a postdoctoral researcher in Jesse Gillis’ lab at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. “People come to this question with many different techniques, whether they are looking at the shape or the connectivity or the electrophysiological properties.”

Crow recently received a two-year grant from the National Institutes of Health to try to measure and explain the diversity of interneurons that, down the road, could have implications for neurological diseases or disorders in which an excitatory stimulus lasts too long.

“Understanding interneuron diversity is one of the holy grails of neuroscience,” explained Gillis in an email. “It is central to the broader mission of understanding the neural circuits which underlie all behavior.”

Crow plans to use molecular classifications to understand these subtypes of neurons. Her “specific vision” involves exploiting “expected relationships between genes and across data modalities in a biologically thoughtful way,” said Gillis.

Crow’s earlier research suggests there are 11 subtypes in the mouse brain, but the exact number is a “work in progress,” she said.

Her work studying the interneurons of the neocortex has been “some of the most influential work in our field in the last two to three years,” said Shreejoy Tripathy, an assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Toronto. Tripathy hasn’t collaborated with Crow but has been aware of her work for several years.

The interactivity of a neuron is akin to personalities people demonstrate when they are in a social setting. The goal of a neuronal circuit is to take an input and turn it into an output. Interneurons are at the center of this circuit, and their “personalities” affect the way they influence information flow, Crow suggested.

“If you think of a neuron as a person, there are main personality characteristics,” she explained. Some neurons are the equivalent of extraverted, which suggests that they have a lot of adhesion proteins that will make connections with other cells.

“The way neurons speak to one another is important in determining” their classes or types, she said.

A major advance that enabled this analysis springs from new technology, including single-cell RNA sequencing, which allows scientists to make thousands of measurements from thousands of cells, all at the same time.

“What I specialize in and what gives us a big leg up is that we can compare all of the outputs from all of the labs,” Crow said. She is no longer conducting her own research to produce data and, instead, is putting together the enormous volume of information that comes out of labs around the world.

Using data from other scientists does introduce an element of variability, but Crow believes she is more of a “lumper than a splitter,” although she would like to try to understand variation where it is statistically possible.

She believes in using data for which she has rigorous quality control, adding, “If we know some research has been validated externally more rigorously than others, we might tend to trust those classifications with more confidence.”

Additionally she plans to collaborate with Josh Huang, the Charles Robertson professor of neuroscience at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, who she described as an interneuron expert and suggested she would use his expertise as a “sniff test” on certain experiments.

At this point, Crow is in the process of collecting baseline data. Eventually, she recognizes that some interneurons might change in their role from one group to another, depending on the stimuli.,

Crow hasn’t always pursued a computational approach to research.

In her graduate work at King’s College London, she produced data and analyzed her own experiments, studying the sensory experience of pain.

One of the challenges scientists are addressing is how pain becomes chronic, like an injury that never heals. The opioid crisis is a problem for numerous reasons, including that people are in chronic pain. Crow was interested in understanding the neurons involved in pain, and to figure out a way to treat it. “The sensory neurons in pain sparked my general interest in how neurons work and what makes them into what they are,” she said.

Crow indicated that two things brought her to the pain field. For starters, she had a fantastic undergraduate mentor at McGill University, Professor of Psychology Jeff Mogil, who “brought the field to life for me by explaining its socio-economic importance, its evolutionary ancient origins, and showed me how mouse behavioral genetic approaches could make inroads into a largely intractable problem.”

Crow also said she had a feeling that there might be room to make an impact on the field by focusing on molecular genetic techniques rather than the more traditional electrophysiological and pharmacological approaches.

As for computational biology, she said she focuses on interpreting data, rather than in other areas of the field, which include building models and simulations or developing algorithms and software.

In the bigger picture, Crow said she’s still very interested in disease and would like to understand the role that interneurons and other cells play. “If we can get the tools to be able to target” some of the cells involved in diseases, “we might find away to treat those conditions.”

The kind of research she is conducting could start to provide an understanding of how cells interact and what can go wrong in their neurodevelopment.

Gillis praises his postdoctoral researcher for the impact of her research.

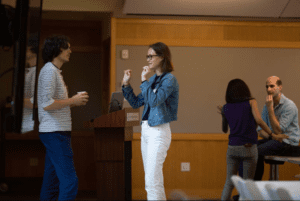

“Just about any time [Crow] has presented her work — and she has done it a lot — she has ended up convincing members of the audience so strongly that they either want to collaborate, adapt her ideas, or recruit her,” Gillis wrote in an email.

Crow grew up in Toronto, Canada. She said she loved school, including science and math, but she also enjoyed reading and performing in school plays. She directed a play and was in “The Merchant of Venice.” In high school, she also used to teach skiing.

A resident of Park Slope in Brooklyn, Crow commutes about an hour each way on the train, during which she can do some work and catch up on her reading.

She appreciates the opportunity to work with other researchers at Cold Spring Harbor, which has been “an incredible learning experience.”