Reviewed by Jeffrey Sanzel

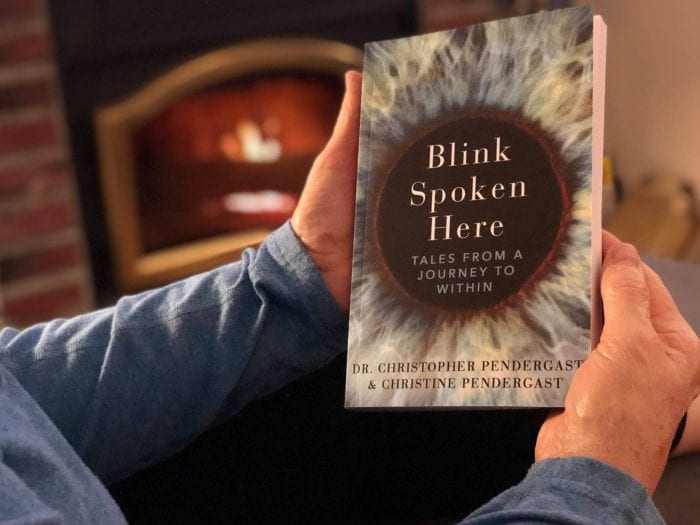

The name of the book is Blink Spoken Here. It is written by Dr. Christopher Pendergast and Christine Pendergast of Miller Place.

That’s really all you need to know.

That, and please buy the book.

Blink Spoke Here. Dr. Christopher Pendergast and Christine Pendergast. Buy the book.

You don’t need to finish reading this review.

You just need to buy the book.

Blink Spoke Here. Dr. Christopher Pendergast and Christine Pendergast. Please buy the book. Now.

For those who want to know more …

It is easy to say that this is an important book — because it is. It is about exceptional bravery in the face of unfathomable adversity. It is about a man who has defied the odds and lived with one of the single most difficult and devastating diseases: ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. Emphasis on lived with. It is told in his words, with the assistance of his wife.

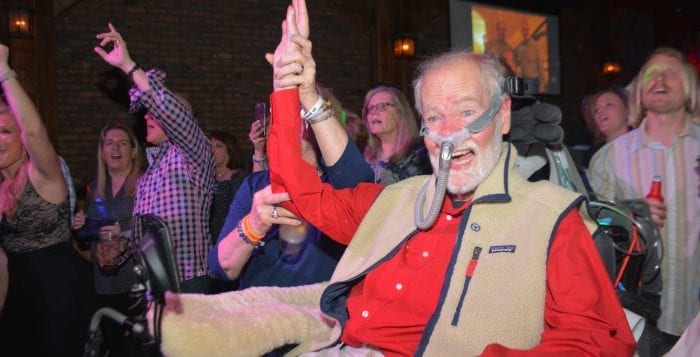

The title refers to how he wrote the book, with an eye-controlled device, as he does not have the use of his hands or his voice. His journey began with the diagnosis in 1993 and continues to this very day — to the very moment that you are reading this sentence. The average lifespan with ALS is two to five years; Dr. Pendergast has survived for twenty-seven. There is no medical answer as to why. But perhaps the Universe has chosen him for bigger reasons. Two of them? First: his bringing awareness to this monstrous affliction through his inspirational Ride For Life. Second: He has written this book.

In 1993, Dr. Pendergast had been a teacher for twenty-three years, married to his childhood sweetheart, Christine. At the time of his diagnosis, he was in the Northport school district, and he continued to teach in the classroom for as long as possible. When that was no longer an option, he continued as a teacher for the world. Blink Spoken Here is a portrait of a teacher in the best sense of the word. His passion to impart knowledge has infused his entire life.

Beginning with a description of the disease’s arc, he brings us into his world:

“It was not a dramatic event like a building collapse but a more steady deterioration similar to a bridge failure. I was imploding. In 1993, my physical presence began shrinking before my very eyes. My contact with the world was severing, one function at a time. Angry, scared and saddened I was like a stubborn mule fighting with tenacity for each inch I surrendered. First it was dressing, followed by grooming, driving, toileting, walking, feeding, and breathing. Now I cling to my last vestiges of talking. It forced me retreat towards within. The exterior husband, father, and friend was left behind.”

Dr. Pendergast is unflinching in his brutal honesty about the pains and the challenges. He shares some of the darkest moments in his life. But, just as often, he speaks of hope and appreciation and deep faith. Many of the simplest things that we take for granted have been taken from Dr. Pendergast. And yet, in all of this, he manages to find not just the good in life but the lessons that are offered every day.

If these are not good enough reasons to read this book (and they should be), it is also a beautiful piece of writing. Dr. Pendergast writes with extraordinary eloquence and sincerity, with humor and insight. His prose is exquisite. He shares anecdotes and parables, free verse and personal accounts. The craft is equal to the art and both are worthy of the humanity that created it.

If these are not good enough reasons to read this book (and they should be), it is also a beautiful piece of writing. Dr. Pendergast writes with extraordinary eloquence and sincerity, with humor and insight. His prose is exquisite. He shares anecdotes and parables, free verse and personal accounts. The craft is equal to the art and both are worthy of the humanity that created it.

The memoir is split into two sections. The first focuses on his coming to terms with the disease and its myriad challenges. (The first half even concludes with a wicked send-up of Dr. Seuss.)

The second half of the book focuses on the Ride for Life, which began in 1998 as the Ride to Congress. It follows his goals of bringing national awareness to ALS as well as an increase in services, knowledge, and fundraising. Taking his cue from the activism of the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, he finds his inspiration:

“For me, the remarkable results of these movements underscored the power of choosing to make a difference. The activists of those movements did more than complain about these wrongs; rather they opted to fight for change. This activism formed a model in my subconscious. I followed this model 40 years later.”

The initial support of his home school in Northport proves that it takes a village — or at least a district. Over the years, the Ride has evolved and has focused its activities in New York and Long Island.

From the “weight of secrecy” to his global advocacy, this is an odyssey that is both far-reaching and personal. His love for his wife and family and for his community comes through at every turn. This is a man who does not curse the darkness but moves towards the light.

“Life is too short to spend wishing things were not so. Things are what they are. Some occurrences are not our choice. However, we do choose how to respond. We decide how to live the life we get.”

There are too many incredible moments to enumerate. Even the description of the challenge of opening an envelope is a revelation. There is a particularly telling incident with his son and church. It is a lesson in forgiveness and perspective, and its reverberations reflect his own continuing journey.

The final chapter, entitled “The First Amendment,” is a crushing account of his loss of the ability to speak: “To the educator, the voice is a powerful tool. It commands respect, informs and on occasion, inspires. The voice becomes our signature for the world. Losing it is catastrophic.”

Dr. Pendergast describes the gradual decline in his vocal power and the various methods of communication. His frustration is honest and palpable just as his deep belief that his and all voices should be heard in one form or another. He advocates for those who are desperately ill with ALS and that this basic human right should not terminate at the hospital door.

“Speech is freedom. Communication is the connection to the outside world. We all have a right to be heard … I want to be able to speak, even if it is only one blink at a time.”

This chapter brilliantly closes the book. Because while he may have lost the physical voice, his spiritual voice continues. It is powerful. It commands respect. It informs. And, truly and always, it inspires.

Once again.

Blink Spoken Here. Dr. Christopher Pendergast and Christine Pendergast.

Don’t wait. Please buy this book. Now.

Blink Spoken Here: Tales From a Journey Within (Apprentice House Press) is available at Book Revue in Huntington, Amazon.com and BarnesandNoble.com.