The transformation of Upper Port is happening in real time after years of well-documented social issues and underinvestment.

In the coming weeks, the village will complete two major initiatives. Station Street will soon open to traffic, and the Port Jefferson Crossing apartments, a 45-unit affordable housing complex developed by Conifer Realty, will launch.

As these projects open, further planning is in full swing. Conifer is working with the Village of Port Jefferson Planning Board on a second development located at the Main and Perry streets intersection. Meanwhile, the Board of Trustees is actively pursuing a vision for the proposed Six Acre Park along Highlands Boulevard.

In an exclusive interview with Mayor Margot Garant, she summarized the activities. “I think we’ve made great progress,” she said. “I think it’s a great start to what will continue to make [Upper Port] a safe and welcome place.”

Completing these projects marks the next chapter in a multiyear village undertaking to revitalize its uptown. Yet as the area undergoes its metamorphosis, a broader conversation is emerging.

Community revitalization in context

‘

A good plan is the genesis of effort and conversation between the constituents, elected officials, economists, environmentalists, civic organizations, resident groups, business owners and, yes, real estate developers.’

— Richard Murdocco

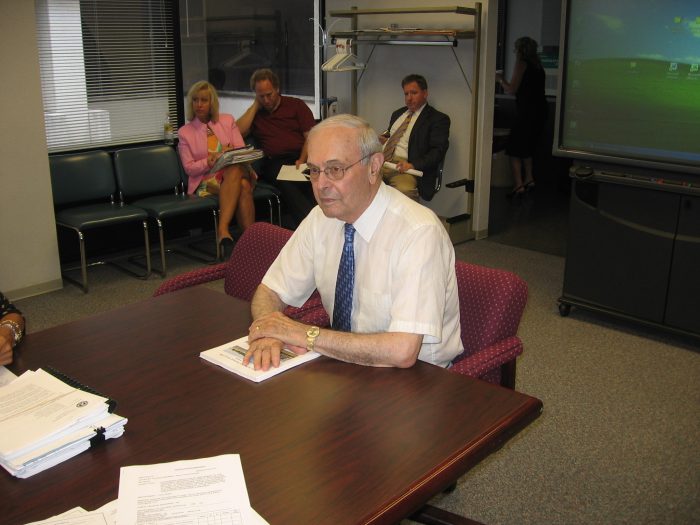

Richard Murdocco is an adjunct professor in the Department of Political Science at Stony Brook University. His writings focus on land use, economic development and environmental policies on Long Island. In an interview, Murdocco detailed the regional and historical context surrounding redevelopment efforts in Port Jeff.

Downtown revitalization on Long Island dates back at least six decades, said Murdocco, when communities started tackling the effects of suburbanization and population boom.

“Downtown revitalization is not anything new,” Murdocco said. “The first comprehensive plans were drafted in the early ’60s by the Long Island Regional Planning Board and Dr. Lee Koppelman. Those identified key downtown areas where to focus growth, and the whole point of the plans was to mitigate the ever-ongoing suburban sprawl that western Suffolk County, especially, was getting a taste of at that time.”

With the eastward expansion of the Northern State Parkway and the construction of the Long Island Expressway, downtown areas soon became targets for growth. Ideally, this growth consisted of additional multifamily housing options, expanded retail sectors and developing neighborhoods near train stations.

Although development plans today are often pitched as novel or innovative, Murdocco contends that the general framework underlying revitalization has been replicated across generations.

“These concepts are as old as city building,” he said. “It may be new for Long Island, but it’s not new in practice.”

The Patchogue model

‘For an area to be successful, there has to be people and there has to be a reason for people to be there.’

— Paul Pontieri

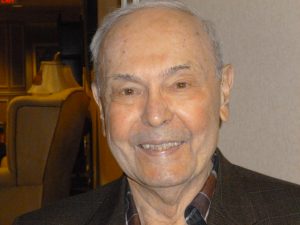

Today, proponents often cite the Village of Patchogue as a cornerstone of community revitalization on Long Island. Spearheading these efforts is Paul Pontieri, who has served as the village’s mayor since 2004.In an interview, Pontieri detailed his approach to community building. For him, areas that thrive are those with people.

“For an area to be successful, there has to be people and there has to be a reason for people to be there,” he said. “Businesses go where people are.”

Another priority for Pontieri was attracting young families into Patchogue. “We have a lot of young families,” he said. “That happened because we provided the kind of housing they can afford.”

Apartments were central for creating affordable housing options, according to Pontieri. While existing rents may appear overpriced to some, he believes these rent payments are preferable to the mandatory down payments when taking out a mortgage.

“Right now, if you have to put 20% down on a $500,000 home, you’re telling me that a 22- or 23-year-old that just got married has $100,000 to give on a down payment — it’s not going to happen, and that’s the reality,” he said. “You have to have the apartments because they will come into the apartments and begin to save their money, even though the rents on those apartments seem exorbitant.”

Pontieri holds that Long Island communities today face the challenge of drawing and keeping youth. According to him, young people will inevitably move away from unaffordable areas.

“You have a choice: You can sit there in your house — you and your wife at 75 years old — and your kids move someplace else because they can’t afford to live in your village,” he said, “Or you make your community user-friendly, kid-friendly, young-family friendly.”

Murdocco said Patchogue had been held up as the standard-bearer for community rejuvenation because Pontieri more or less carried his vision through to completion. Though revitalization brought unintended consequences for Patchogue, such as magnifying a “parking problem that was enhanced and amplified by growth,” Murdocco said the example is generally regarded favorably.

“Overall, it’s lauded as a model because they did it,” the adjunct professor said. “For all intents and purposes, the area is thriving relative to what it was.”

Differentiating Upper Port

‘Our little footprint can’t really hold as much as Patchogue.’

— Margot Garant

While Garant acknowledges the utility of Pontieri’s method for Patchogue, she points out some key distinctions unique to Upper Port.Like Pontieri, she holds that the neighborhood’s success depends on the people it can attract. “I believe that new residents and the new opportunity will drive an economic base and new economic success,” she said. Though arriving at this new resident base, Garant is employing a different approach.

For one, the two villages differ widely concerning their respective topographies. When organizing a plan, Garant said Port Jefferson must operate within the confines of limited space, further constrained by the existing built environment.

“Patchogue is flat, and it’s a grid system, so you can spread out there and have larger parcels that connect to the heart of your village,” she said. “In Port Jefferson, we’re in a bowl. We’re surrounded very much by residential [zones] on both sides of Main, so I see us as able to grow a bit differently.”

Tying into the issue of topography is the matter of density. Garant maintains Pontieri had greater flexibility, enabling vertical and horizontal expansion to accommodate a growing population. “Our little footprint can’t really hold as much as Patchogue,” Garant said.

Applying the Patchogue model to Upper Port is further complicated by the historical and cultural differences between the two villages. Garant stated she intends to bring a family oriented culture to Upper Port. In contrast, Patchogue attracts a more robust nightlife scene accentuating its bar and restaurant culture.

“I just have a different philosophy when trying to revitalize the neighborhood,” Garant said. “I think Patchogue became known for the young, jet-setting community, the Alive After Five [street fair] bringing people to Main Street with a different sort of culture in mind. We’re looking at making things family oriented and not so much focused on bars and restaurants.”

In an email statement, trustee Lauren Sheprow, who emphasized revitalizing Upper Port as part of her campaign earlier this year, remarked that she was impressed by the ongoing progress. She remains committed to following the guidelines of the Port Jefferson 2030 Comprehensive Plan, published in 2014.

Referring to the master plan, she said, “It does appear to be guiding the progress we are seeing take shape uptown. It would be interesting to take a holistic look at the plan to see how far we have progressed through its recommendations, and if the plan maintains its relevance in current times where zoning is concerned, and how we might be looking at the geography east of Main Street.”

Six Acre Park

‘The Six Acre Park is something that I see as a crucial element to balancing out the densification of housing up there.’

— Rebecca Kassay

Along with plans for new apartments, Garant said the proposed Six Acre Park would be integral to the overall health of Upper Port. Through the Six Acre Park Committee, plans for this last sliver of open space in the area are in high gear. [See story, “Six Acre Park Committee presents its vision.”]

Trustee Rebecca Kassay is the trustee liaison to the committee. She refers to the parkland as necessary for supporting new residents moving into the village.

“As far as Upper Port, I am hoping and doing what I can to plan for a vibrant, balanced community up there,” she said. “The Six Acre Park is something that I see as a crucial element to balancing out the densification of housing up there.”

With more density, Kassay foresees Six Acre Park as an outlet for the rising population of Upper Port. “Everyone needs a place to step out from a suburban or more urban-like setting and breathe fresh air and connect to nature,” she said. “The vision for Six Acre Park is to allow folks to do just that.”

In recent public meetings, a debate has arisen over a possible difference of opinion between the village board and the planning board over active-use space at Six Acre Park. [See story, “PJ village board … addresses Six Acre Park.”]

Garant said the Board of Trustees has yet to receive an official opinion on behalf of the Planning Board. Still, the mayor does not see sufficient reason to modify the plan.

“We’re talking about creating an arboretum-like park used for educational purposes,” she said. “At this point in time, we don’t have enough land. The uptown population is welcome to use the rest of the parkland throughout this village.” Garant added, “But we are extremely mindful that when the new residents come to live uptown and they bring their needs, there’s a lot more that’s going to happen uptown and a lot more opportunity for us to make adjustments.”

Identifying the public good

‘In my opinion, property owners have allowed their buildings to deteriorate so that they would be able to sell the properties to — in this case — subsidized developers.’

— Bruce Miller

New development, in large part, is made possible by the Brookhaven Industrial Development Agency, which can offer tax exemptions to spur economic growth. Former village trustee Bruce Miller has been among the critics of Upper Port redevelopment, taking issue with these IDA subsidies.“It’s an open secret that the properties were very poorly maintained up there,” Miller said. “In my opinion, property owners have allowed their buildings to deteriorate so that they would be able to sell the properties to — in this case — subsidized developers.”

In Miller’s assessment, while the projects are taxpayer supported, their community benefit is outweighed by the cost to the general fund.

“The buildings that are being built are paying very little in the way of taxes,” Miller said. “At 10 years it ramps up, but even at 15 years there’s not much tax they’re paying on them.”

Responding to this critique, Lisa Mulligan, CEO of Brookhaven IDA, released the following statement by email: “In accordance with our mission, the Brookhaven IDA is committed to improving the quality of life for Brookhaven residents, through fostering economic growth, creating jobs and employment opportunities, and increasing the town’s commercial tax base. The revitalization of uptown Port Jefferson is critical to the long-term economic well-being of the region, and housing is one key component of this.”

Town of Brookhaven Councilmember Jonathan Kornreich (D-Stony Brook), who represents Port Jefferson on the Town Council, also took issue with Miller’s claim. For him, the purpose of IDA subsidies is to identify benefits to the community and advance the public good.

“So often, there is no public benefit,” he said. “If it’s the will of Port Jefferson Village to revitalize an area that has struggled to attract investment for many years, that may be an appropriate use of IDA funding.”

However, Kornreich also acknowledged that these tax incentives come at a cost for ordinary taxpayers. For this reason, it remains crucial that the IDA has a firm grasp of the public good and advances that end alone.

“When this unelected body gives these benefits to a developer, it’s a tax increase on everyone within that taxing district … they are increasing your taxes,” the councilmember said. “When you pay those increased taxes, what you’re doing is supporting this vision of a public good.” In instances where the IDA functions without a view of the public good, he added, “It’s a huge betrayal.”

Garant suggested that ridding Upper Port of vacant lots constituted a public good in itself. While IDA benefits may mean short-term sacrifices for village residents, the tax exemptions will soon expire and the village will collect its usual rates.

“For us in the short term, we might be making a little bit of a sacrifice, but I can tell you right now what I’m making on the payment in lieu of taxes program is more than what I was getting on those buildings when they were blighted,” she said. “Six, seven, eight years down the road, when we’re at the end of those PILOT agreements, we’re going to be getting a sizable tax contribution from these properties.” She added, “I was looking down a 10- to 15-year road for the Village of Port Jefferson.”

Murdocco foresees opportunities for continued discussions within the village. According to him, community development done right is highly collaborative, uniting the various stakeholders around a common aim.

“A good plan is the genesis of effort and conversation between the constituents, elected officials, economists, environmentalists, civic organizations, resident groups, business owners and, yes, real estate developers,” he said. “I know for a fact that in Upper Port Jefferson, a lot of that did happen.”

The SBU adjunct professor added, “In terms of defining a public benefit, it depends on what the community wants. Do they want economic growth for an underutilized area? Do they want environmental protection? Do they want health and safety? That all depends on the people who live there.”