By Daniel Dunaief

Good news for shellfish eaters on Long Island.

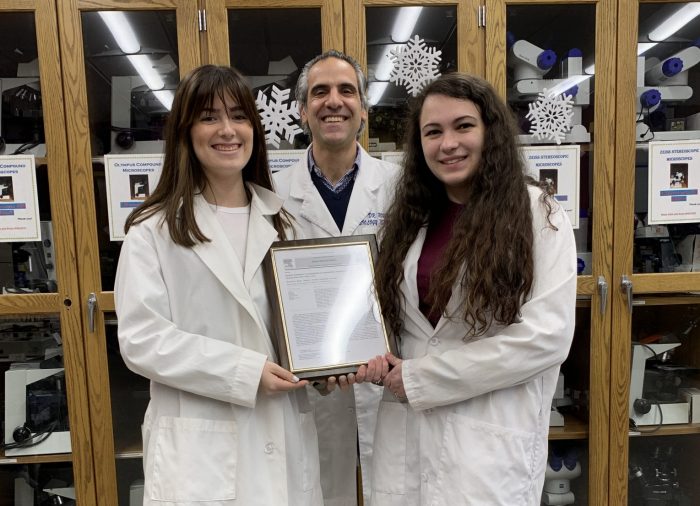

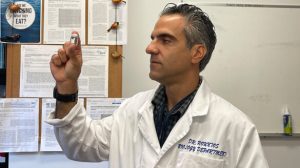

According to a baseline study conducted by recent St. Joseph’s University graduates in the lab of Associate Professor Konstantine Rountos, oysters and hard clams have less microplastics than they do in other areas in the United States and the world.

Caused by the breakdown of larger plastic pieces, pellets used in plastics manufacturing and from micro beads that can be a part of cosmetics, microplastics are found throughout the world and can float around waterways for extended periods of time.

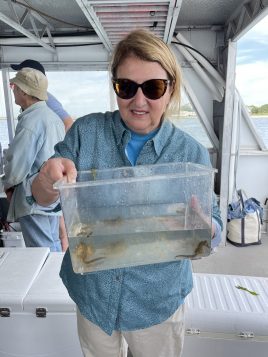

Filter feeders like clams and oysters, which play a key environmental role in cleaning local water, could accumulate microplastics. Researchers don’t yet know the potential harm to humans from consuming shellfish with microplastics.

“I was optimistic that the concentrations are lower than with shellfish in other countries and definitely in other areas of the United States, so that’s a positive for Long Island shellfish growers,” Rountos said. “It’s good for seafood lovers, too.”

To be sure, Rountos cautioned that more research was necessary to explore the concentrations of smaller microplastics to provide a more complete understanding of the accumulation of these particles. Nonetheless, he described this step in the study as “positive.”

In other areas of the country, previous studies revealed a higher concentration of microplastics in local shellfish. In the lower Chesapeake Bay, researchers found concentrations of 5.6 to 7 microplastics per gram of soft tissue in eastern oysters, while other scientists found concentrations of 0.56 to 2.02 microplastics per gram in soft tissue in oysters and 0.38 to 1.99 microplastics per gram of soft tissue weight in hard clams.

By contrast, Rountos, Mackenzie Minder, who is the first author on the paper, and Isabella Colombo discovered in their study of 48 oysters at four sites on Long Island was 1,000 times lower with eastern oysters. They also discovered no microplastics in hard clams at two sites around the island.

The lower numbers on Long Island may also be a product of the sieve size Rountos and his students used, which may not have captured smaller particles.

In a paper published in Marine Pollution Bulletin, Mackenzie, Colombo and Rountos suggested that one potential explanation for the difference in microplastics concentrations could arise from the potentially lower levels of microplastics in the surrounding water.

Other proposed studies are exploring the concentration of microplastics in local waterways.

Gordon Taylor, Professor and Division Head in Marine Sciences and Director of the NAno-Raman Molecular Imaging Laboratory, has two grant applications pending to sample Long Island waters, including the Long Island Sound, Peconics, Great South Bay and the New York Bight. His plan is to sample true microplastics in the water, through beach surveys and microplastics eaten by zooplankton.

Taylor will combine these observations with physical oceanography to model where these particles originate and where they are going.

Bringing research to the classroom

Photo from Konstantine Rountos

For Minder and Colombo, both of whom are now teaching on Long Island, publishing their work offered a welcome and exciting conclusion to their college studies, while also giving them ways to inspire their students.

“This allows me to bring real life experience [in research] into the classroom,” said Minder. “It’s important to me to connect to children certain concepts of what they see in everyday life. Pollution could potentially impact our waterways to the point where it could be getting into our food supplies and could affect us physically and mentally.”

Minder said the study “opened my eyes to see how subconsciously we are putting plastics in the environment” through activities like washing synthetic fibers.

A fleece with synthetic fibers has “plastics that you wash and those fibers end up in the water,” Rountos said.

Some cosmetics such as exfoliators used to have microspheres that ended up in the water. Many cosmetic companies are now using bits of coconuts for grittiness.

Undergrad power

Rountos appreciated the reaction from Minder and Colombo, who earned degrees in adolescent biology education, when he suggested they could publish their research. He said his two former students “dove in head first” and the three had regular meetings to draft the manuscript and address reviewer’s revisions and recommendations.

Minder and Colombo are pleased with the paper “It’s shell shocking,” Minder said.

A resident of Hauppauge, Minder, whose hobbies include crocheting and reading, appreciates how her family has been showing copies of the paper to their friends and enjoys seeing the paper on refrigerators in her parents’ and grandmother’s homes.

A resident of Sayville, Colombo is serving as a building substitute for students who are 10 to 14 years old.

The research experience taught Colombo the value of communication, dedication and responsibility, which she has brought to the classroom. When she tells high school students about the publication, her students ask for signed copies of the paper.

“It’s such an honor and a privilege to be a part” of such a research effort, Colombo said.

Colombo’s family, who is proud of her for her work, is also relieved that she didn’t find the kind of contamination that might cause anxiety about the seafood they eat.

“Considering how many times I eat it for the holidays I was very concerned” about what they’d find, Colombo said.

Despite the trace amount of microplastics, Colombo and her family will continue to eat shellfish. She plans to hang the framed copy of the paper Rountos gave her in a future classroom.

Colombo decided to go into teaching after taking a living environment class with Sayville educator Cindy Giannico. She is grateful to Giannico for captivating “my desire to learn more and appreciate how applicable science is to your everyday life.”

Colombo has since come full circle and has been a student teacher in Giannico’s class. Giannico was thrilled to welcome Colombo, whom she recalled as “hard working” and “helpful” with other students even as a tenth grader, back to the classroom.

Colombo has since taken a job as a science teacher on Long Island. Giannico believes Colombo has forged a strong connection with her students through her caring and consideration and her willingness to work with them.

“Most people feel comfortable around her,” Giannico said. “She’s really mature.”

Colombo’s published work has sparked student interest in conducting their own research studies.

Rountos is proud of Minder and Colombo’s contribution. He described Colombo and Minder as “rare gem” students.