By Daniel Dunaief

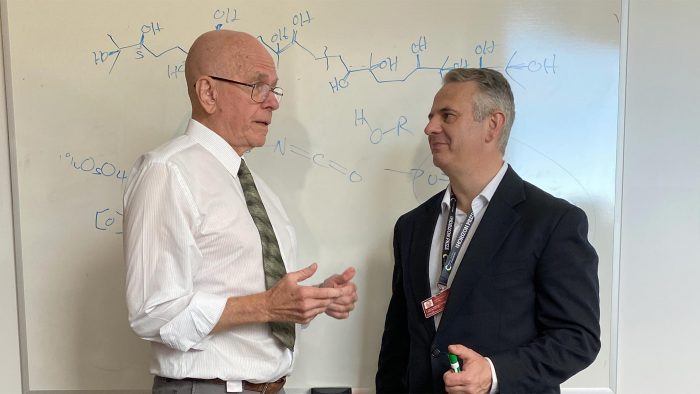

As the first chemist in the history of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Professor John Moses has forged new connections at the lab, even as he maintains his affinity for and appreciation of his native Wrexham in Wales.

Indeed, Moses recently created and funded a fellowship for disadvantaged students in Wales, giving them an opportunity to visit the lab, learn about the science he and others do, and, perhaps, spark an interest in various science, technology, engineering and math fields.

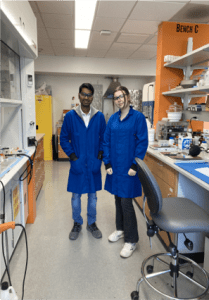

Called Harbwr y Ffynnon Oer Scholarship, which means “Cold Spring Harbor” in Welsh, Moses’s laboratory recently welcomed Jasmine Moss, the first recipient, in early August.

“I hope it broadens” the horizons of those who travel to the lab, explained Moses in an email. “Wales is a small country” with a population of about three million. Coming to New York — a city with a much bigger population than Wales — “can only be an eye-opening experience.”

For Moss, who is studying for an integrated masters degree in biomedical engineering, the opportunity proved exciting and rewarding.

“I was expecting to feel intimidated” with everyone knowing so much more than she, Moss said during an interview on the morning of her third day in the lab. “I was expecting maybe a little bit not to understand everything. Everyone is amazing” and made her feel welcome.

The experience started with a walk around the campus, which included considerable information not only about the science but also about the history of the 133-year old laboratory.

Moss, who said this was the first time she’d been in a professional chemistry lab, helped conduct an experiment in which a reaction caused a liquid to change color because of the presence of copper.

“I did the measuring and putting it together,” said Moss, who added that she was “heavily supervised.” She did some calculations as well.

Moss suggested that her interest in science originated with a proficiency in math.

If she were having a bad day in secondary school, she could turn her mood and her mentality around by spending an hour in math class.

Beyond the science

Theresa Morales, a senior scientific administrator, created a schedule of activities and coordinated Moss’s visit.

“We want to do the same thing for any scholarship awardee,” Morales said. “We want to give them the overall experience. It’s not just about the science. We invite the person to realize the culture of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory” which has a “beautiful campus and great people” who occupy its labs, attend meetings, and share scientific insights and experiences.

A postdoctoral researcher in Moss’s lab, Josh Homer suggested that Morales did “the heavy lifting” in coordinating three days of activities and opportunities for Moss. Homer, who is collaborating with Professor Bo Li to develop new opiates that are non addictive for pain treatment, appreciated Moss’s reactions to the opportunities in the lab.

“I thought [Moss’s] face lit up,” he said. When people are exposed to science in a “manageable and digestible way, they learn that they can do it.”

Indeed, Homer, who grew up in New Zealand, recalled how a high school teacher inspired his interest in science.

“My journey genuinely kick started from one good teacher” who sparked an “inquisitiveness” within him, Homer said.

Coming from a smaller country, Homer can relate to the opportunities science has provided for him.

“Chemistry has been a fantastic way to see the world and explore,” said Homer, who conducted his PhD research at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. “Science is a universal language. Chemistry is the same in India, China” and all over the world.

A family experience

Moss traveled to New York for the first time with her parents Stephen and Emma, who stayed with her on campus, toured the grounds and library and attended a picnic.

While the library tour was less interesting to Moss, she said her father “really enjoyed it.”

Morales suggested that the lab “wants parents to feel just as good” and that the parents will have “the same enthusiasm for science and the experience as the scholar if they can feel they are a part” of the visit.

In addition to getting an inside look at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Moss and her parents ventured into the city, where she ate her first pizza and visited the Empire State Building and the Statue of Liberty. She was particularly impressed with the speed at which the Empire State Building was constructed, which took a year and 45 days.

Prior to her visit, Moss’s understanding of the city of New York came from the version she observed through the sitcom “Friends.”

As for the next phase of her life, she expressed an interest in helping people, which could be through medical engineering, biology or in some other field.

“I want to do something meaningful,” Moss said.

Next steps

Moses hopes to bring students to the lab each year, particularly those who might have had problems or difficulties or are from a disadvantaged background. Moss suffers from anxiety and feels every new experience makes similar opportunities easier.

“The team really put me at ease almost immediately,” said Moss.

Moss was surprised by the similarities between Long Island and the United Kingdom. She suggested the best parts of Wales are the countryside and beaches. If she returned the favor and hosted guests in her native Wales, she would take them to an international rugby match in Cardiff.

As for other area sports, Moses comes from the little soccer town that could in Wrexham, which is now famous for the purchase of the local team by actor Ryan Reynolds and co-owner Rob McElhenney. While the actors have brought soccer dreams to life, Moses hopes Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory might help young students realize their science dreams.