Reviewed by Jeffrey Sanzel

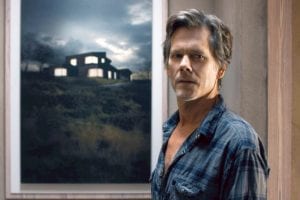

The tagline to the new horror movie Ghosts of War is “The Enemy Isn’t Out There. It’s in Here.” If “in here” meant the studio, I would agree with that. Ghosts of War is presented as a thriller that traces descent into madness. However, writer/director Eric Bress (The Butterfly Effect) misses almost every opportunity to deliver something that is more than just a series of clichés.

The film opens in Nazi occupied France, 1944. The five remaining members of an American troop are ordered to guard a French chateau that was recently occupied by the Nazis. After an opening sequence in which they dispatch a Nazi unit and then aid escaping or refugee concentration camp survivors, they arrive at their destination. (The anachronisms become both clearer and muddier as the film progresses.)

The soldiers who have been holding the mansion until now hightail it out … as if haunted by their experiences there. Subtlety is not Bress’s strong suit. Nor is dialogue or character development.

Within minutes, there is a clumping parade of almost every old-dark-house trope: weird stains and burn marks on the carpet; rows of staring dolls; a wine cellar with a strange family photo; a locked trunk; garbled breathing sounds from ornate vent grates; matches blown out without a breath of air; strange voices in locked rooms; a silhouette of a hanged man that disappears when the curtains billow; doors that swing open suddenly; mysterious footsteps overhead; claw marks on the floor; a pentagram in the attic; … and everything accompanied by a swift camera pan and a crash of the soundtrack.

All of this all happens in about fifteen minutes. One then ponders what they’re going to do for the next hour.

Well … they’re going to talk. They’re going to have a vulgar exchange of stories and urban legends; this is to show that they’re “men.” Then they’re going to have serious philosophical discussions about the nature of evil. And still there’s fifty minutes to go — so Bress recycles the strange voices and the odd knocking and adds some screeching ghosts. (There is one clever piece where the banging actually communicates Morse code.)

The shame is that there are real hints of possibility. Clearly, these five men have been damaged by their wartime experiences. The pain lying underneath the bravado could have been harnessed to tell a story about soldiers transitioning from battle to PTSD. But, instead, Ghosts of War is stilted and predictable. Lines like “I’m not sure what I saw” are followed by quasi-intellectual explorations of the supernatural.

A reference to the Ambrose Bierce short story, “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” and the possibility that they are dead is neatly connected to their speculation on this being their own personal Hell, forced to relive a loop of the same moments. Again, a great idea that is squandered as they return to the same screams and jumps.

A journal left behind reveals that the castle’s residents had hid Jews before they were caught and brutally murdered by the Nazis. It is their spirits that are trapped in the house. Laying them to rest becomes the soldiers’ quest. There is a brief interlude where a random Nazi patrol enters the house and is dispatched by both the Americans and the ghosts — before the ghosts once again turn on the Americans.

Skylar Astin does his best as the “smart one” — he’s the “smart one” because he’s wearing glasses and plays classical piano. Brenton Thwaites finds a decent if predictable footing as the group leader. Kyle Gallner’s sniper is a bit over-the-top twitchy but he’s the only one given any history, including a monologue about his murder of a group of Hitler Youth.

Theo Rossi and Alan Ritchson are fine with what they are given but don’t make much impression. Unfortunately, none of them seem to have any internal background to drive the characters’ motivations. In addition, they are saddled with so much expositional dialogue about hauntings and earthbound spirits that they become overly articulate and lose any individuality.

In the final fifteen minutes of the film, the theme shifts from horror to almost science fiction. What could become an interesting twist about the power of guilt instead becomes a confused and unrealized concept that builds up to literally — and infuriatingly — no ending. The film stops as it is on the cusp of a possible resolution.

It just

(Like that.)

Rated R, Ghosts of War is now streaming on demand.

If these are not good enough reasons to read this book (and they should be), it is also a beautiful piece of writing. Dr. Pendergast writes with extraordinary eloquence and sincerity, with humor and insight. His prose is exquisite. He shares anecdotes and parables, free verse and personal accounts. The craft is equal to the art and both are worthy of the humanity that created it.

If these are not good enough reasons to read this book (and they should be), it is also a beautiful piece of writing. Dr. Pendergast writes with extraordinary eloquence and sincerity, with humor and insight. His prose is exquisite. He shares anecdotes and parables, free verse and personal accounts. The craft is equal to the art and both are worthy of the humanity that created it.

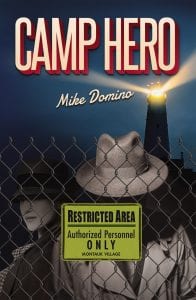

At the center of the story is Camp Hero.

At the center of the story is Camp Hero.

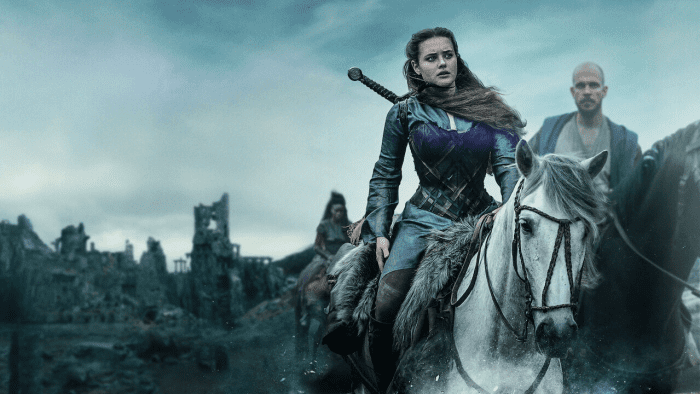

Hamilton: An American Musical (its full title) is the sole creation of the unparalleled Lin-Manuel Miranda who had already risen to prominence with his In the Heights. Miranda used the Ron Chernow biography Hamilton (2004) as his source, but this is no traditional musical biopic. With his unique book, music, and lyrics, he has fashioned a celebration unlike any other, and in doing so, has redefined what theater can be.

Hamilton: An American Musical (its full title) is the sole creation of the unparalleled Lin-Manuel Miranda who had already risen to prominence with his In the Heights. Miranda used the Ron Chernow biography Hamilton (2004) as his source, but this is no traditional musical biopic. With his unique book, music, and lyrics, he has fashioned a celebration unlike any other, and in doing so, has redefined what theater can be. Over the years, there have been various attempts to bring the experience of live theater to television with varying success. The American Playhouse presentation of Into the Woods (1991) was one of the stronger examples, featuring the show’s original cast. The Public Theatre’s presentation of The Apple Plays, composed of four plays by Richard Greenburg, worked extremely well. It’s interesting to note that a fifth Zoom/COVID play presented in April — without an audience — was the best of all of them.

Over the years, there have been various attempts to bring the experience of live theater to television with varying success. The American Playhouse presentation of Into the Woods (1991) was one of the stronger examples, featuring the show’s original cast. The Public Theatre’s presentation of The Apple Plays, composed of four plays by Richard Greenburg, worked extremely well. It’s interesting to note that a fifth Zoom/COVID play presented in April — without an audience — was the best of all of them. One of the treasures of this recorded Hamilton is that it preserves the original company. And this cast is exceptional: a group of young (only two casts members were even in their forties) and astoundingly talented singer/dancer/actors execute a story with not only precision and commitment but unparalleled joy.

One of the treasures of this recorded Hamilton is that it preserves the original company. And this cast is exceptional: a group of young (only two casts members were even in their forties) and astoundingly talented singer/dancer/actors execute a story with not only precision and commitment but unparalleled joy.