Reviewed by Jeffrey Sanzel

“Boy, I hope there’s a really unfunny rom-com to kick-off the holiday season,” said no one ever. But that’s what the Netflix offering Holidate delivers. In place of wit, there is … not wit. Holidate is not even worthy of a deprecatingly clever simile.

The premise is simple and has probably been seen dozens of times. That isn’t necessarily a bad thing. There are many plots that have been revisited over the years. The goal, of course, is to find something fresh, unusual, or intriguing in the situation. Unfortunately, Tiffany Paulsen’s terribly clunky, crass script is further exposed by John Whitesell’s clumsy and pedestrian direction.

Photo courtesy of Netflix

Holidate opens with Sloane (Emma Roberts) still reeling from her break-up six months prior. She is having a Christmas from hell in which she is plagued by her family’s constant harping on her singlehood. Sloane is offered advice from her man-chasing Aunt Susan (Kristin Chenoweth) to always have someone to date for the holiday. In Susan’s case, she has brought home a mall Santa.

Across town, Jackson (Luke Bracey) is having a nightmare of his own, spending the holiday with the family of a girl whom he has only dated three times. It is apparent that the young woman thinks that they are in a much more serious relationship, one that she has shared with her eager family.

The next day Sloane and Jackson meet on a department store return line. What comes of this chance encounter is an agreement to be “holidates” for New Year’s Eve. There is not a great deal of background given to either characters. He is a golf pro; she works remotely. She eats junk food; he does not. He’s Australian; she isn’t. And they’re off.

Freed of expectations, this “mismatched” couple has a good time on New Year’s Eve. There is a cute send-up of Dirty Dancing, evoking a smile if not a full-on laugh. The evening ends awkwardly with Sloane deciding it isn’t worth pursuing.

On Valentine’s Day, Sloane runs into her ex with his new, younger girlfriend. Jackson (who just happens to be walking by the store) rescues her from complete embarrassment by swooping in, pretending to be her significant other. Realizing that the situation will work for them, they agree to be friends without benefits, committing to all calendar celebrations for the foreseeable future.

The film now begins to traverse a year’s worth of holidays: St. Patrick’s Day, Easter, Cinco de Mayo, Mother’s Day, etc. Each seems to be centered around drinking and almost — but not quite — having sex. While their friendship grows, Sloane’s mother (Frances Fisher) is desperately trying to set her up with the new neighbor, nice guy doctor Faarooq (Manish Dayal).

Fourth of July is particularly eventful with Jackson having a finger blown off as the men launch M-80’s. Sloane takes him to the hospital (where the Faarooq happens to be on-call). His finger is re-attached. There are the stirring of sparks between Sloane and Jackson. Will they? Won’t they? Do we care?

Since this is a rom-com, they get their wires crossed, resulting in a crisis with a Labor Day wedding where they choose to bring other dates. Sloane takes the doctor; Jackson brings Aunt Susan. (The resulting aunt-doctor hookup at the wedding becomes a subplot that can be kindly described as cringeworthy.)

Halloween sees them taking their relationship to the next step. But not before a disgusting laxative encounter. Thanksgiving shows their divide, with a dramatic confrontation that aims for soul-searching but winds up to be just being embarrassing. And guess what happens at Christmas?

None of this would be a problem if the film showed a single spark of originality, charm, or warmth. Holidate instead is consistently tasteless — what is less than single entendre? Basically, it’s watered-down Hallmark with an R rating. A raunchy, crude comedy attempting to make a bigger, heartfelt statement. It achieves being the worst of both worlds. Occasionally, they seem to be sending up the genre but this just confuses and contradicts the majority of the film when they are “being real.” You can’t have it both ways. Or at least they can’t.

The problem is further acerbated by performances that lack subtlety and dimension. Emma Roberts is better than this. Of the cast, she comes across the strongest, but she was given a lot of action but little to play. Luke Bracey is handsome but stiff. Kristin Chenoweth, a truly wonderful performer, is painfully miscast as the vamp; every moment feels excruciatingly forced. If she took the role on to expand her range, she didn’t succeed. If she needed the paycheck, a Go Fund Me would have had more dignity.

The rest of the characters (mostly trope cooky family members) come and go but the director’s complete lack of vision gave no consistent style in which the actors could invest. As a bonus, there are the requisite precocious children who make adult observations and occasionally inappropriate comments.

In the final scene, there was one of maybe three genuinely funny moments in the movie. It involves a Christmas choir at the mall. But one bright note does not a symphony make just as ten clever seconds don’t erase and hour and forty minutes of vulgarity.

Spoiler Alert: Sloane and Jackson end up together. Now you don’t have to watch the movie. You’re welcome.

Holidate is now streaming on Netflix.

I

I

Her “good ingredients” list suggests items that are ideal for the recipes as well as brands to which she has an affinity. “I started calling for specific ingredients because they do make a difference … They don’t have to be expensive but they have to be chosen thoughtfully …”

Her “good ingredients” list suggests items that are ideal for the recipes as well as brands to which she has an affinity. “I started calling for specific ingredients because they do make a difference … They don’t have to be expensive but they have to be chosen thoughtfully …”

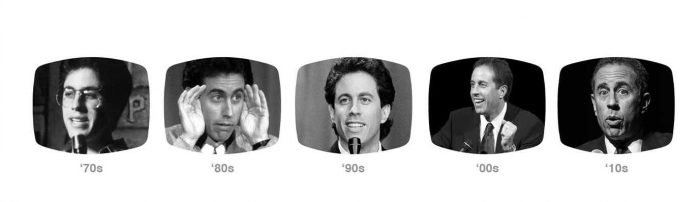

The book records the dozens of jokes that have been part of a four-decade career. It is like visiting old friends, full of ah-hah moments of remembering a particular line or seeing the source for an episode of Seinfeld. (A perfect example is “Dry Cleaning” where he imagines bumping into his dry cleaner wearing his clothes.) It is fortunate that he has kept all his material from the beginning of his career, every idea, every scrap of paper. Even some of his earliest jokes remained in his repertoire twenty and thirty years later. It is a pleasure to read the book and, of course, hear his flawless timing in your mind’s ear.

The book records the dozens of jokes that have been part of a four-decade career. It is like visiting old friends, full of ah-hah moments of remembering a particular line or seeing the source for an episode of Seinfeld. (A perfect example is “Dry Cleaning” where he imagines bumping into his dry cleaner wearing his clothes.) It is fortunate that he has kept all his material from the beginning of his career, every idea, every scrap of paper. Even some of his earliest jokes remained in his repertoire twenty and thirty years later. It is a pleasure to read the book and, of course, hear his flawless timing in your mind’s ear.