A joyous new vision of a Dickens classic

Reviewed by Jeffrey Sanzel

“Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.” — the opening lines of Charles Dickens’ The Personal History of David Copperfield

After Shakespeare (and perhaps J.K. Rowling), Charles Dickens is the most famous writer in the English language. His major works include Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Tale of Two Cities, Bleak House, and A Christmas Carol, with hundreds of stage, screen, and television adaptations.

Charles Dickens began crafting his autobiography in the late 1840s. But he found the writing too painful and burned what he had written. He then fictionalized many of his personal experiences for what became David Copperfield. It is Dickens’ premiere work told in the first person (and note that David Copperfield’s initials are Charles Dickens’ backward, suggesting a reflection of the author himself).

Photo courtesy of Searchlight Pictures

The Personal History of David Copperfield was published in monthly installments, serialized from 1849 to 1850, and then brought out in book form. Dickens’ longest work, Copperfield is rich in plot and contains close to one hundred characters. It is an incredible journey, full of adventure, but it is also about mastering one’s fate, growing from passive child to self-aware adult. Young David is acted upon; adult David is a figure who has taken control of his own life.

The cinematic history includes three silent and over a half dozen others. The most notable is the two-part BBC television version (1999) featuring an extraordinary cast, with Danielle Radcliffe as young David, Bob Hoskins as Mr. Micawber, and Maggie Smith as Aunt Betsey.

The newest incarnation is a unique and slightly madcap adaptation. Directed by Armando Iannucci, from a screenplay by Iannucci and Simon Blackwell, it condenses the epic novel into a brisk, laugh-out-loud, and always heartfelt two hours. The choices are often wild and surprising, but no moment, no matter how peculiar, departs from the vision’s integrity.

The film opens with David Copperfield (a mesmerizing Dev Patel, reinventing the role) reading his book to a packed theatre. But is it David or Charles Dickens? Ultimately, it is both. He states the first two lines and then literally steps into the story, being present at his own birth.

Baby David’s arrival coincides with the appearance of his late father’s aunt, Betsey Trotwood (impeccably played by Tilda Swinton, swanning through the story like a cross between a tornado and neurotic albatross). She declares herself the child’s godmother, leaving when presented with a boy and not the girl she was demanding. It is a comic rollercoaster of a scene, tumultuous and culminating with Betsey exiting in high dudgeon. And so begins David’s life.

Young David (Jairaj Varsani, a child performer of exceptional skill) has an idyllic childhood. He is loved by a doting mother (the delicate and sweet Morfydd Clark) and his even more attentive nursemaid Peggotty (genuine warmth and personal proverbs as played by Daisy May Cooper). The peace is shattered by his mother’s remarriage to Edward Murdstone (terrifying in Darren Boyd’s cold-eyed villainy). Murdstone’s abuse of David begins the cycle of flux that he will face for the rest of his life. He gains, then loses, then recovers, only to lose again.

Eschewing the boarding school section, David is banished to the blacking factory, sentenced to work in miserable conditions. This pivotal juncture is taken directly from the darkest chapter of Dickens’ childhood, one he kept secret his entire life. David boards with penurious Micawber (Peter Capaldi, artfully blending the kind and the con) and his ever-growing family. It seems that every time David meets up with the Micawber family, they have added a baby to the ever-expanding brood.

Micawber and his wife (bubbling and bug-eyed Bronagh Gallagher) are hunted and haunted by creditors, much like Dickens’s own father: Both the Micawbers and Dickens’ parents wound up in debtors’ prison. The Micawbers are Dickens’ gentle depiction of his parents, for whom he bore a life-long grudge due to his exile to the blacking factory. Later, Capaldi is pathetically outrageous as Micawber attempts — and fails — to teach a Latin lesson.

Unlike in the novel, the factory sequence shows David’s transition from boy to man. When Murdstone informs him of his mother’s death, David’s reaction is violent, more reminiscent of Nicholas Nickleby beating the schoolmaster than the always put-upon and long-suffering David Copperfield. Iannucci’s vision is self-actualized and capable of independence.

David walks from London to Dover, seeking sanctuary with his Aunt Betsey. Even under duress, he aids Betsey’s lodger, the eccentric Mr. Dick (heart-breaking and hilarious Hugh Laurie, a man with the delusion that the decapitated King Charles I’s thoughts have been placed in his head).

In the bosom of his remaining family, David thrives (for a while). There is romance and adventure, complications and resolutions. The film handles them with quick turns, ranging from near-slapstick to deep introspection. The narrative is rich in whimsy but doesn’t avoid the darkness. The characters retain the vivid character traits endowed by Dickens but are enriched with inner lives.

David’s creativity is highlighted, even as a young child. He spins yarns and draws sketches, heralding the great writer. Like Dickens, he jots down unusual phrases and collects the people in his life, developing them in the mirror.

There is a meta-cinematic quality about the film, often breaking (and literally tearing) the fourth wall to allow the characters to observe or even flow into other scenes. The film’s colors are lush and rich, leaning towards childhood fantasy, but can quickly shift to somber shades. As a child, the seaside town of Yarmouth was a place of storybook magic; when David returns, it is a place of shadows.

In addition to the previously mentioned cast members, note should be made of Rosalind Eleazar, who makes the intolerably insipid Agnes Wickfield a strong, likable foil for the maturing David. Clark, who plays young David’s mother, Clara, doubles beautifully as David’s love interest Dora Spenlow — endearing, exhausting, and empty-headed. Uriah Heep, usually much oilier and damp in his “umble” sycophancy, is more dangerous in Ben Whishaw’s performance. Paul Whitehouse’s Mr. Peggotty is appropriately paternal; Benedict Wong brings tannic notes to the dissipated Mr. Wickfield.

Whether it is colorblind or color-conscious, casting director Sarah Crowe has perfectly gathered an enormous, multi-racial company, flawless from Dev Patel’s dimensional, delightful David to Scampi, who plays Dora’s dog Jip.

While Iannucci takes liberties with much of the novel, most notably in the latter half’s rushed solution, this Copperfield celebrates the original by transcending it. The film culminates with a catharsis rooted in hope. Perhaps purists would lean towards the more complete and faithful 1999 version, but in the spirit and the sense of joy, the new David Copperfield is wholly satisfying.

Rated PG, the film is now streaming on Amazon Prime Video.

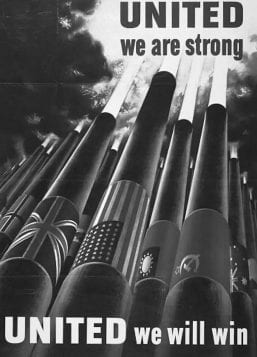

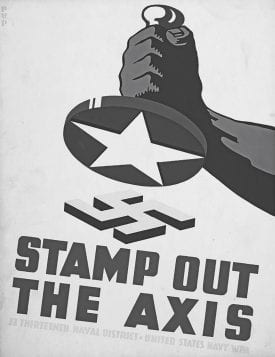

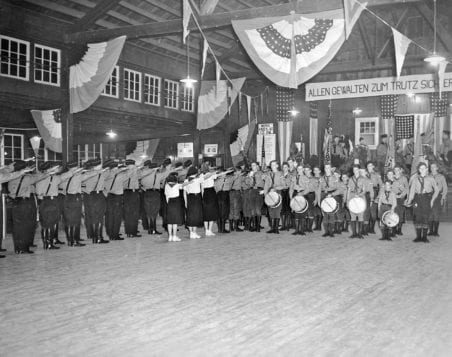

Much of the book covers the shift that came with the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The attack spurred civilian involvement along with unification behind the war effort. He documents the early failures and gradual shift to competency in air raid drills across the Island. This example also emphasizes the growing cooperation between the military and non-military populations.

Much of the book covers the shift that came with the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The attack spurred civilian involvement along with unification behind the war effort. He documents the early failures and gradual shift to competency in air raid drills across the Island. This example also emphasizes the growing cooperation between the military and non-military populations.

In addition to his wide-eyed and well-intentioned if slightly oblivious royal, Murphy and co-star Arsenio Hall each played another three supporting roles. The film was funny, raunchy, and a huge hit. While critical response was mixed, it was a financial success. Coming to America was Paramount’s highest-earning film and the third-highest-grossing film in United States box office. Its worldwide total is estimated as high as $350 million. (It is Eddie Murphy’s eighth highest-grossing film.)

In addition to his wide-eyed and well-intentioned if slightly oblivious royal, Murphy and co-star Arsenio Hall each played another three supporting roles. The film was funny, raunchy, and a huge hit. While critical response was mixed, it was a financial success. Coming to America was Paramount’s highest-earning film and the third-highest-grossing film in United States box office. Its worldwide total is estimated as high as $350 million. (It is Eddie Murphy’s eighth highest-grossing film.) Meanwhile, Zamunda faces a threat from its militaristic neighbor Nextdoria, ruled by dictator General Izzi (Wesley Snipes). Izzi is the older brother of Imani (Vanessa Bell Calloway), who Akeem jilted in the first film. Upon discovery that Akeem has a successor, the General wants Lavelle to marry his daughter Bopoto (Teyana Taylor). All of this frustrates Akeem’s capable eldest daughter, Princess Meeka (KiKi Layne), who aspires to run the kingdom. While being trained as a prince, Lavelle falls in love with his no-nonsense royal groomer Mirembe (Nomzamo Mbatha).

Meanwhile, Zamunda faces a threat from its militaristic neighbor Nextdoria, ruled by dictator General Izzi (Wesley Snipes). Izzi is the older brother of Imani (Vanessa Bell Calloway), who Akeem jilted in the first film. Upon discovery that Akeem has a successor, the General wants Lavelle to marry his daughter Bopoto (Teyana Taylor). All of this frustrates Akeem’s capable eldest daughter, Princess Meeka (KiKi Layne), who aspires to run the kingdom. While being trained as a prince, Lavelle falls in love with his no-nonsense royal groomer Mirembe (Nomzamo Mbatha). The movie has a few strong moments. One of the best scenes involves a job interview. Lavelle comes into direct conflict with white privilege, embodied by Mr. Duke (Colin Jost). The scene is genuinely funny—Lavelle uses his “white voice” to attempt to secure a position for which he is qualified but under-educated. The encounter reflects Lavelle’s day-to-day challenges. It helps that Fowler has an easy charm and is genuinely likable. His strut is a thin mask for a good young man who wants to grow into a better adult. He never severs his connection to his Queens roots but is open to what Zamunda has to offer. Fowler owns his hero’s journey.

The movie has a few strong moments. One of the best scenes involves a job interview. Lavelle comes into direct conflict with white privilege, embodied by Mr. Duke (Colin Jost). The scene is genuinely funny—Lavelle uses his “white voice” to attempt to secure a position for which he is qualified but under-educated. The encounter reflects Lavelle’s day-to-day challenges. It helps that Fowler has an easy charm and is genuinely likable. His strut is a thin mask for a good young man who wants to grow into a better adult. He never severs his connection to his Queens roots but is open to what Zamunda has to offer. Fowler owns his hero’s journey. Both Jones and Morgan have the same material they’ve been given elsewhere but usually better crafted. As they have cornered the particular brand of humor, their laughs come easily but their sources are uninspired. In contrast, Layne and Mbatha play it straight and come out with dignity if no laughs.

Both Jones and Morgan have the same material they’ve been given elsewhere but usually better crafted. As they have cornered the particular brand of humor, their laughs come easily but their sources are uninspired. In contrast, Layne and Mbatha play it straight and come out with dignity if no laughs.

Troy’s presence has always been a negative force, and incarceration has made him both bitter and dangerous. Now, he has concocted a murder and kidnapping scheme based on a chance encounter at a service station. Once set in motion, he recruits Mac, a former prison mate, to facilitate the latter part of the crime. Troy forces Lorraine into taking part:

Troy’s presence has always been a negative force, and incarceration has made him both bitter and dangerous. Now, he has concocted a murder and kidnapping scheme based on a chance encounter at a service station. Once set in motion, he recruits Mac, a former prison mate, to facilitate the latter part of the crime. Troy forces Lorraine into taking part: