By John L. Turner

This is the second in a two-part series on Long Island’s water supply.

‘We Have Met the Enemy and He is Us’ — Pogo

Imagine, for a moment, you’re driving on a road that skirts one of New York City’s water supply reservoirs such as the Croton or Ashokan reservoir. You come around a bend and in a large gap in the forest, offering a clear and sweeping view of the reservoir, you see thousands of houseboats dotting the reservoir’s surface. An unease falls over you — after all this is a drinking water reservoir that supplies drinking water to millions of people — and letting people live on their water supply doesn’t seem like a very good idea to ensure the purity or even the drinkability of the water.

Shift your focus to Long Island and you can see these “houseboats.” They’re in the form of hundreds of thousands of homes and businesses sitting on the surface. The drinking water reservoir however is invisible beneath our feet, leading to a “out-of-sight, out-of-mind” mentality, which, in turn, has led to decades of mistreatment by the approximately 2.7 million Long Islanders who live, work, and play above a water supply they cannot see. Perhaps it is this visual disconnection which explains the checkered stewardship.

At the risk of understatement, Long Island’s drinking water system, and the coastal waters hydrologically connected to it, are facing significant, big-time challenges. By just about any measure (a few exceptions include detergents and several types of pesticides) there are more contaminants in greater concentrations in Long Island’s groundwater than any time in its history.

In a way this is not surprising as Long Island has built out with a land surface containing ever increasing numbers of actual and potential sources of contamination, and hundreds of poorly vetted chemicals coming on the market every year. Layer on this the quantity dimension: that in certain areas there’s simply not enough water to meet current or projected human demand and the needs of ecosystems (like wetlands) and it’s not surprising that Long Island’s drinking water system is under stress like never before.

To be clear, government agencies have not sat passively by in an effort to protect and manage the aquifer system. There are many examples over the past several decades where various government agencies, statutorily responsible for safeguarding our water resources, have delineated a problem and moved to address it. Let’s run through a few.

You’ve heard the expression: “oil and water don’t mix.” The same is true for gasoline, as evidenced by the many leak and spill incidents in the past caused by hundreds of gasoline stations scattered throughout Nassau and Suffolk Counties. As more and more contamination was discovered from gasoline plumes in the Upper Glacial aquifer half a century ago, gasoline storage tanks buried at every filling station were becoming known as “ticking time bombs”. This is because tanks installed many decades ago were single-wall, and made of corrodible cast iron — two undesirable traits for tanks containing thousands of gallons of gasoline buried in the ground.

The solution? Both counties mandated tank replacement; Suffolk County through the enactment of Article 12 of the Suffolk County Sanitary Code. New requirements included double-walled fiberglass or specialized steel tanks with a leak detection system in between the two walls to detect a leak in the inner wall. Older readers may remember, years ago, the presence of excavators and backhoes in gas stations throughout the island as the industry moved to comply with this important new water quality safety measure. Because of these two county laws gasoline leaks — and subsequent plumes — from station tanks are almost entirely a thing of the past.

Another pollutant that is largely a thing of the past is salt. Before the adoption of legislation mandating the enclosed covering of salt piles managed by transportation and public works departments, stockpiled for winter road deicing applications, salt piles would sit outside exposed to the elements. Not surprisingly, plumes of salty water, well above drinking water standards, often formed under these piles. In some cases plumes beneath salt piles located near public water supply wells ended up contaminating these wells. Today, by law, all highway department salt stockpiles have to be covered or indoors to prevent saltwater plumes.

Nitrogen pollution has been a more intractable problem. Emanating from centralized sewage treatment plants, agricultural and lawn fertilizers, and many thousands of septic tanks and cesspools (there’s an estimated 360,000 of them in Suffolk County alone), nitrogen is ubiquitous. This excess nitrogen has fueled adverse ecological changes in our estuaries including loss of salt marshes and various types of toxic algae blooms, which in turn, have killed off scallops, clams, diamondback terrapins, and blue-claw crabs. Too much nitrogen in drinking water can have adverse health consequences for humans, especially babies, a concern since an increasing number of public wells have nitrogen levels exceeding the state health limit of 10 parts per million.

So how to get ahead of the nitrogen curve? Generally there are three ways, each relating to each of the major sources of contamination — 1) nitrogen laden water from home septic tanks/cesspools, 2) nitrogen laden water from sewage treatment plants, and 3) nitrogen pollution stemming from fertilizer use, most notably in farming but also by homeowners for lawn care.

Through the Septic Improvement Program, under its “Reclaim Our Water” Initiative, Suffolk County has thrown its eggs in the “septic tank/cesspool” basket by attacking the nitrogen generated by homeowners. How? By working with companies that have made vast improvements in the technology used to treat household sewage; basically these companies have developed mini-sewage treatment plants in place of septic tanks/cesspools, resulting in much lower nitrogen levels in the water recharged into the ground (from 70 to 80 parts per million ppm nitrogen to 10-20 ppm.

The County now provides financial subsidies to homeowners to replace aging systems with new Innovative/Advanced systems (known as I/A systems). The downside with this approach is that because of the huge number of homes that need to convert their cesspools/septic tanks to I/A systems (remember the 360,000 figure from above?) it will take many decades to bend the nitrogen-loading curve meaningfully downward, to the point we’ll begin to see a difference.

An additional complimentary approach to reduce nitrogen loadings, but likely able to do so more quickly, is through the tried and true strategy of “water reuse.” Here, highly treated wastewater from sewage treatment plants (STP’s) which contains low concentrations of nitrogen, is used in ways which “pulls out” the nitrogen. Water reuse is common practice in many places in the United States including Florida and California where the trademark purple-colored distribution piping is commonplace. Approximately 2.6 billion gallons of water is reused daily in the country, mostly for golf course irrigation but also for irrigating certain foods such as citrus trees.

The largest water reuse example on Long Island involves the Riverhead STP-Indian Island County Golf Course. With this project, from April to October, highly treated wastewater is directed to the adjacent Indian Island County Golf Course rather than being discharged into the Peconic River. According to engineering projections, the effort annually results in about 1.4 less tons of nitrogen entering the estuary, being taken up by the grass, and keeps about 63 million gallons of water in the ground since golf course wells no longer need to pump irrigation water from the aquifers.

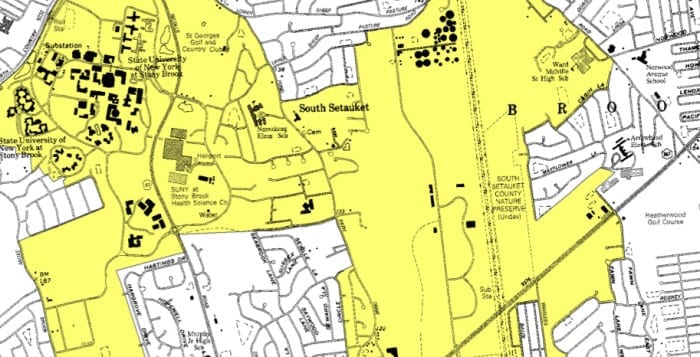

With funding support the Seatuck Environmental Association has hired Cameron Engineering & Associates to develop an islandwide “Water Reuse Road Map” to guide future reuse projects. A potential local project, similar to the Riverhead example, tentatively identified in the roadmap involves redirecting wastewater from the SUNY Stony Brook STP which currently discharges into Port Jefferson Harbor and use it to irrigate the St. Georges Golf Course and Country Club, situated several hundreds away from the STP on the east side of Nicolls Road in East Setauket.

The third source of nitrogen contamination — fertilizers — has also received focus although progress here has been slower. A Suffolk County law, among other things, prohibits fertilizer applications from November 1st through April 1st when the ground is mostly frozen and little plant growth occurs. It also prohibits, with certain exemptions such as golf courses, fertilizer applications on county-owned properties. Several bills, both at the county and state level, have been introduced to limit the fraction of nitrogen in fertilizer formulations and to require “slow release” nitrogen so it can be taken up by plants and not leach into groundwater.

A basic concept that has emerged from a better understanding of how Long Island’s groundwater system works and the threats to it, is the value of the aforementioned “deep-flow recharge areas” serving as groundwater watersheds, these watersheds recharging voluminous amounts of water to the deepest portions of the underlying aquifers. And we’ve also learned “clean land means clean water.”

Where the land surface is dominated by pine and oak trees, chipmunks, native grasses, blueberries, etc., the groundwater beneath is pure, as there no sources of potential contamination on the surface. It has become clear that Long Island’s forested watersheds play an important role in protecting Long Island’s groundwater system.

In recognition of the direct relationship between the extent to which a land surface is developed and the quality of drinking water below it, a state law was passed establishing on Long Island SGPA’s — “Special Groundwater Protection Areas” — lightly developed to undeveloped landscapes within the deep-flow recharge zones that recharge clean water downward, replenishing the three aquifers; the 100,000 acre Pine Barrens forest being the largest and most significant SGPA.

There are seven other SGPA’s including the Oak Brush Plains SGPA just east of Commack Road and south of the Pilgrim State Hospital property; the South Setauket SGPA in northwestern Brookhaven Town, bisected by Belle Meade Road; one on the North Fork; two on the South Fork; and two in northern Nassau County. These areas collectively recharge tens of millions of gallons of high to pristine quality water to the groundwater system on a daily basis. The state law mandated the development of a comprehensive plan designed to safeguard the land surface and the water beneath it in all the SGPA’s. Landscape protection took a step further in the Pine Barrens, where state law has safeguarded nearly 100 square miles of land from development.

Protecting a community’s water supply has been a challenge throughout recorded history. Many past dynasties and civilizations (e.g. China, Bolivia, Cambodia, Egypt, Syria, southwest United States) have collapsed or been compromised by failing to ensure adequate supplies of clean water. In modern times maintaining the integrity of a water supply has become one of the fundamental responsibilities of government. It is clear that various levels of government, from Washington, DC, to Albany, to local governments, have advanced a host of laws, regulations, strategies, and programs all designed to safeguard our water supply.

The jury is still out, though, as to whether this collective governmental response will be adequate enough. While Pogo has been correct so far — we, the 2.7 million Long Islanders in the two counties have been the enemy — perhaps with the implementation of additional proactive responses we might prove the little opossum wrong.

A resident of Setauket, John Turner is conservation chair of the Four Harbors Audubon Society, author of “Exploring the Other Island: A Seasonal Nature Guide to Long Island” and president of Alula Birding & Natural History Tours.