By Daniel Dunaief

There may be no crying in baseball, as Tom Hanks famously said in the movie “A League of Their Own,” but there is, thanks to San Francisco Giants and Alyssa Nakken, now a woman in baseball.

Last week, for the first time in the 150-year history of the game, a woman joined the ranks of the coaches at Major League level.

The hiring of Nakken, 29, follows the addition of women in the National Football League and the National Basketball Association.

While it may seem past time that America’s pastime caught up with the times, members of the Long Island athletic and softball communities welcomed the news.

“I hope that it becomes more of the norm rather than the exception,” said Shawn Heilbron, athletic director at Stony Brook University.

For Megan Bryant, who has been the head softball coach at Stony Brook since 2001 and has collected more than 870 career wins, Nakken’s new job creates a path that others can follow.

“For the Giants and Major League Baseball and women in sports careers, that’s a big deal and is a step forward,” Bryant said. “It will open other doors for other women.”

Bryant said teams can and should recognize the wealth of coaching talent among men and women.

“If you’re a great coach, it shouldn’t matter the gender of the athletes you’re coaching,” Bryant said.

Lori Perez, who was an assistant softball coach at Sacramento State University when Nakken played and is now head coach, said the news gave her “goose bumps.”

The hardworking Nakken, a two-time captain at Sacramento State, once asked her coaches to stop a low-energy practice so the team could refocus and flush their negative energy, Perez said.

Nakken’s parents had “high expectations for her but, even better, she had high expectations for herself,” which included doing well academically and helping out in summer camps, Perez said.

Patrick Smith, athletic director at Smithtown school district, believes these first few female hires in men’s sports are a part of a leading edge of a new trend.

“We will see more and more [women joining professional sports teams] as time goes on,” Smith said. In Smithtown, women constitute greater than half of all the athletes at the high school level.

Among the six senior women on Stony Brook’s softball team, three members are considering a career in sports after they graduate, Bryant said.

While the Women’s College World Series softball games have drawn considerable fan attention, attendance at women’s college and professional sporting events typically lags that of men.

The Long Island community can provide their daughters with a chance to observe and learn from role models at the college and professional levels by attending and supporting local teams.

“It’s frustrating that the women’s games aren’t drawing close to what the men’s teams are,” said Heilbron. The Stony Brook women’s basketball team, which includes standout junior India Pagan among other talented players, is currently 18-1. This is the best start in program history.

“I hope people will come” support the team, Heilbron said. “If you come, we believe you’ll come back.”

As for women in high profile roles, Bryant, who is looking forward to the addition of six new players to her softball squad this year, believes each step is important on a longer journey toward equal opportunity.

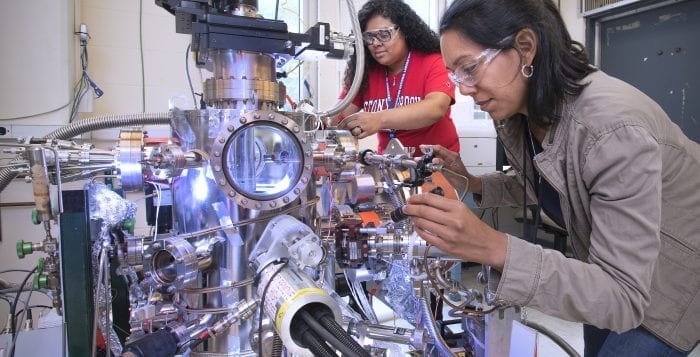

“Whether it’s in sports, science or politics, we’re making strides,” Bryant said. “But we still have a long way to go.”

Perez, who has two children, is thrilled that “women can dream of things they couldn’t dream of before,” thanks to Nakken and other female trailblazers inside and outside of the sports world.