By Daniel Dunaief

For many young children, the ideal peanut butter and jelly sandwich doesn’t include any crust, as an accommodating parent will trim off the unwanted parts before packing a lunch for that day.

Similarly, the genetic machinery that takes an RNA blueprint and turns it into proteins includes a so-called “spliceosome,” which cuts out the unwanted bits of genetic material, called introns, and pulls together exons.

When the machinery works correctly, cells produce proteins important in routine metabolism and everyday function. When it doesn’t function correctly, people can contract diseases.

Danilo Segovia, a PhD student at Stony Brook University who has been working in the laboratory of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Professor Adrian Krainer for seven years, recently published a study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences about an important partner, called DDX23, that works with the key protein SRSF1 in the spliceosome.

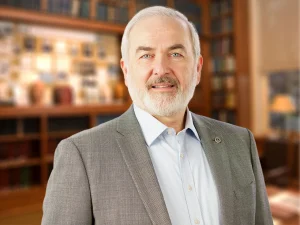

“We obtained new insights into the splicing process,” said Krainer, who is the co-leader of the Gene Regulation & Inheritance program in the Cancer Center at CSHL. “The spliceosome is clearly important for every gene that has introns and every cell type that can have mutations.”

Krainer’s lab has worked with the regulator protein SRSF1 since 1990. Building on the extensive work he and members of his lab performed, Krainer was able to develop an effective treatment for Spinal Muscular Atrophy, which is a progressive disease that impacts the muscles used for breathing, eating, crawling and walking.

In children with SMA, Krainer created an antisense oligonucleotide, which enables the production of a key protein at a back up gene through more efficient splicing. The treatment, which is one of three on the market, has changed the prognosis for people with SMA.

At this point, the way DDX23 and SRSF1 work together is unclear, but the connection is likely important to prepare the spliceosome to do the important work of reading RNA sequences and assembling proteins.

Needle in a protein haystack

Thanks to the work of Krainer and others, scientists knew that SRSF1 performed an important regulatory role in the spliceosome.

What they didn’t know, however, was how other protein worked together with this regulator to keep the machinery on track.

Using a new screening technology developed in other labs that enabled Segovia to see proteins that come in proximity with or interact with SRSF1, he came up with a list of 190 potential candidates.

Through a lengthy and detailed set of experiments, Segovia screened around 30 potential proteins that might play a role in the spliceosome.

One experiment after another enabled him to check proteins off the list, the way prospective college students who visit a school that is too hilly, too close to a city, too far from a city, or too cold in the winter do amid an intense selection process.

Then, on Feb. 15 of last year, about six years after he started his work in Krainer’s lab, Segovia had a eureka moment.

“After doing the PhD for so long, you get that result you were waiting for,” Segovia recalled.

The PhD candidate didn’t tell anyone at first because he wanted to be sure the interaction between the proteins was relevant and real.

“Lucky for us, the story makes sense,” Segovia said.

Krainer appreciated Segovia’s perseverance and patience as well as his willingness to help other members of his lab with structural work.

Krainer described Segovia as the “resident structural expert who would help everybody else who needed to get that insight.”

Krainer suggested that each of these factors had been studied separately in the process, without the realization that they work together.

This is the beginning of the story, as numerous questions remain.

“We reported this interaction and now we have to try to understand its implications,” said Krainer. “How is it driving or contributing to splice assembly.”

Other factors also likely play an important role in this process as well.

Krainer explained that Segovia’s workflow allowed him to prioritize interacting proteins for further study. Krainer expects that many of the others on the list are worth further analysis.

At some point, Krainer’s lab or others will also work to crystallize the combination of these proteins as the structure of such units often reveals details about how these pieces function.

Segovia and Krainer worked together with Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Professor Leemor Joshua-Tor, who does considerably more biochemistry work in her research than the members of Krainer’s lab.

When a cowboy met a witch

A native of Montevideo, Uruguay, Segovia came to Stony Brook in part because he was conducting research on the gene P53, which is often mutated in forms of human cancer.

Segovia had read the research of Ute Moll, Endowed Renaissance Professor of Cancer Biology at Stony Brook University, who had conducted important P53 research.

“I really liked the paper she did,” said Segovia. “When I was applying for college in the United States for my PhD, I decided I’m for sure going to apply to Stony Brook.”

Even though Segovia hasn’t met Moll, he has benefited from his journey to Long Island.

During rotations at CSHL, Segovia realized he wanted to work with RNA. He found a scientific connection as well as a cultural one when he discovered that Krainer is from the same city in Uruguay.

Krainer said his lab has had a wide range of international researchers, with as many as 25 countries represented. “The whole institution is like that. People who go into science are naturally curious about a lot of things, including cultures.”

Segovia not only found a productive setting in which to conduct his PhD research, but also met his wife Polona Šafarič Tepeš, a former researcher at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory who currently works at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research. Tepeš is originally from Slovenia.

The couple met at a Halloween party, where Segovia came as a cowboy and Tepeš dressed as a witch. They eloped on November 6, 2020 and were the first couple married after the Covid lockdown at the town hall in Portland, Maine.

Outside of the lab, Segovia enjoys playing the clarinet, which he has been doing since he was 11.

As for science, Segovia grew up enjoying superhero movies that involve mutations and had considered careers as a musician, scientist or detective.

“Science is universal,” he said. “You can work wherever you want in the world. I knew I wanted to travel, so it all worked out.”

As for the next steps, after Segovia defends his thesis in July, he is considering doing post doctoral research or joining a biotechnology company.