By Corey Geske

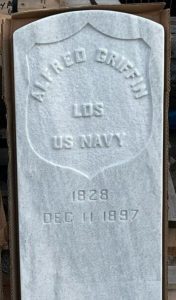

Trustees of the Hauppauge Rural Cemetery connected to the Hauppauge United Methodist Church have sponsored marble markers for previously unmarked graves of Civil War veterans. The first inscribed is for Alfred Griffin, a Landsman, U.S. Navy, former enslaved and self-emancipated Black man whose first name and record were previously unknown. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs engraved and delivered the government headstone to be placed at his gravesite. Cemetery Trustees and the Society of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a non-profit fraternal organization, plan a graveside rededication ceremony on Saturday, June 17 at 10 a.m. at the cemetery adjacent to the Church. That weekend precedes the federal holiday of Juneteenth, which marks the end of slavery in the U.S. in 1865.

Built in 1806, the Hauppauge church and its cemetery in the township of Smithtown were listed in 2020 on the State and National Registers of Historic Places. The Hauppauge Rural Cemetery includes veterans from as far back as the Revolutionary War through today. The cemetery’s Civil War markers tell of young Wessels Payne (1844-1864) killed at Fort Harrison, VA by a Rebel sharpshooter and Daniel O. Hubbs (1835-1862), who died on the USS Horace Beals near Fort Jackson, LA, blockading Confederate ports in Gulf waters where Alfred Griffin escaped enslavement and joined the U.S. Navy.

Fought to be free to fight

Since his death 125 years ago, generation to generation at the church remembered that Mr. Griffin [first name unknown] made his escape from enslavement and fought in the Civil War. Cemetery Trustees have long sought to identify Mr. Griffin’s full name. Their oral history provided enough clues for me to reconstruct his life story in my 2021 report “Enslaved, Escaped, Emancipated, Enlisted,” referenced by Veterans Affairs and on file with the State of New York Office of Historic Preservation.

Searching for Mr. Griffin’s identity

My search for Mr. Griffin’s first name and life dates across seventy years of census data extended to possible family in the Hauppauge area. In 1900, one possible relation, age 10, named ‘George Griffin,’ was boarding at a Hauppauge home next door to a brick mason west of the church. The 1900 and 1910 censuses, recording parental birthplaces, documented George’s father as born in Florida and Alabama, respectively, suggesting he may have been an enslaved brick mason working at U.S. forts built from millions of bricks near Pensacola, FL. It began to look like George’s father could be Mr. Griffin. In 1920, George was living in Bay Shore and veterans’ records brought to light his full name, ‘George Alfred Griffin’ (1890-1974), offering two potential first names for his father.

Relying on church history relating Mr. Griffin was a veteran, I located an ‘Alfred Griffin’ born in Pensacola, FL in the ship’s crew of the USS Circassian’s 1863 muster rolls posted by the National Parks Service. His veterans pension [November 23, 1895] was subsequently located, with his mark signed at Smithtown to his statement, “My correct name is Alfred Griffin . . . I do not write. . .” When census data, military records, and newspaper primary sources were put together, they provided answers once lost to enslavement.

The previously “unknown” Alfred Griffin was born circa 1828 and died December 11, 1897. Mr. Griffin’s just-identified Brooklyn Daily Eagle obituary [December 13, 1897], described him as a mechanic and brick mason, “highly respected . . . in the community,” but did not mention his Navy service. Now, Mr. Griffin’s ‘ship’ has been set right by the Hauppauge church’s collective memory, proved to correspond directly to his life.

Freed ‘off Mobile’

Courtesy Naval History and Heritage Command.

On July 6, 1861, twelve weeks after the Civil War began, two Black persons, ’Alfred’ and ‘George,’ were granted their independence off Mobile, AL. When brought aboard the 860-ton U.S. Steamer Huntsville, part of the Union’s Gulf Blockade Squadron patrolling the Confederacy’s coastline from Key West, FL to Mexico, Commander Cicero Price (1805-1888) effectively emancipated them.

Entered into the muster roll as “Supernumeraries” added to a crew already at its prescribed number of 64, Alfred and George were protected as part of the ship’s complement. Implementing the July 4, 1776 Declaration of Independence proclaiming “all men are created equal,” and eighteen months before President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation freeing the enslaved, future Commodore Price wasted no time putting pen to paper. He had already fought for emancipation, having seen the horrors of enslavement before the Civil War, when serving on the U.S. Africa Squadron blockading enslavers’ ships on the Atlantic enslavement trade’s dreaded Middle Passage that transported kidnapped African people to enslaved labor.

Eyewitness to ‘Freedom’s Fortress’

‘Alfred’ added the surname ‘Griffin’ to his person when officially enlisting aboard the Huntsville on November 25, 1861. He soon saw action fighting the Confederacy. Off Mobile Bay, Christmas Eve, 1861, Huntsville engaged in an hour-long battle turning back the Florida, a steamer of superior force challenging the Union blockade, followed in January 1862, with Huntsville assisting in capturing a rebel schooner, again off Mobile.

Then, on December 9, 1863, in one of the most internationally famous Union Navy victories of the Civil War, Alfred’s next ship, the USS Circassian, captured the British blockade runner Minna near Wilmington, NC, severing an international lifeline supplying the South’s ironclad fleet. The Circassian towed its prize to the Virginia coast, where Alfred Griffin saw the Union’s Fort Monroe, the so-called ‘Freedom’s Fortress,’ granting sanctuary to thousands of escaping enslaved people, many joining the Union Army.

Brick mason builds in Smithtown

Mr. Griffin was honorably discharged in New York, the Huntsville’s port of launch, when that ship was decommissioned in 1862. He reenlisted in the Navy and served as a Landsman into 1864. After the war, he returned to New York and became a resident of Brooklyn, working as a ‘boss’ brick mason, described in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle as doing the work of two men, setting 4,000 bricks in a day.

Mr. Griffin and his family moved to Smithtown in the early 1880s apparently influenced by Rev. Henry Highland Garnet (1815-1882). At age fifteen, after having escaped enslavement, Garnet was given sanctuary in 1830, at the Smithtown home of Epenetus Smith II (1769-1832) before it was moved.

In a Brooklyn sermon of 1879, Garnet said of Epenetus’s son Samuel Arden Smith (1804-1884) then in attendance, “if I have ever been useful to you or to the world, it was greatly owing to him; and I desire those of my friends who feel so disposed to come up to this stand and be introduced to him.” Garnet, a renowned abolitionist, would be the first Black speaker to deliver a sermon before the U.S. House of Representatives, marking Congressional passage of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing enslavement; the new law of the land proclaimed December 18, 1865.

In the early 1880s, Mr. Griffin appears to have built his home of brick in Smithtown Branch south of Main Street on Hauppauge Road (Route 111), neighboring Samuel Arden Smith. The Smith family inherited the fortune of merchant A.T. Stewart (1803-1876), including his Garden City Company brick business, which supplied bricks used in Smithtown, likely by Mr. Griffin.

Later moved east on Main Street to the Smithtown Historical Society grounds, the ‘Epenetus Smith Tavern’ where Garnet received sanctuary in 1830, was originally located north of Main, proximate to today’s Town Hall near where the Smithtown Branch Methodist Episcopal Church was then located, and where Mr. Griffin’s funeral was held.

Smithtown’s freed enslaved men and women would regularly meet about a block south and in 1910, their descendants would build Trinity African Methodist Episcopal Church on New York Avenue. Alfred Griffin was a prosperous mechanic, skilled brick mason known for his business ethic, and member of the fraternal organization of Free and Accepted Masons that worked to build the African American community after the war.

Alfred Griffin’s known descendants

Alfred Griffin married Mary Dixon (c. 1850-aft. 1897-before 1900), whose father born in the West Indies was possibly enslaved. Their children included Mary (c. 1873-unknown); Corie (c. 1876-c. 1899), and George Alfred. Corie Griffin Jackson had three children born in Hauppauge: Alonzo, Paul, and Cora.

Little is known of ‘George,’ rescued with ‘Alfred’ in July 1861, both assigned the singular job of “steward” aboard the Huntsville, suggesting, perhaps, that Alfred brought a young son on his journey to freedom. We do know Alfred Griffin’s son born in 1890 in Smithtown Branch, was named ‘George Alfred Griffin.’

A U.S. Army veteran Of World War I, George, a carpenter, married Minnie Mitchel (c. 1889-aft. 1938), a widow with two daughters, Daisy and Marguerite. The Griffins’ daughter, Jean, was born c. 1927. In 1918, Minnie was a founder of Bethany Baptist Church, built near the Griffins’ home, likely with George’s expertise, and dedicated in 1921, becoming First Baptist Church on Second Avenue in Bay Shore.

About the author: Independent historian Corey Geske of Smithtown has identified lost titles of Hudson River School paintings mistitled on museum and library walls, as well as internationally known, yet forgotten owners and architects of Smithtown’s historic structures. Since 2016, to generate incoming grant money for downtown Smithtown, she has proposed recognition of historic places, notably through a new National Register Historic District focused on the c. 1752 Arthur House, identifying it as the home of Mary Woodhull Arthur, daughter of Washington’s chief spy, Culper, Sr. She prepared the report resulting in determination of the Smithtown Bull as Eligible for the National Register (2018) and wrote the successful National Register nominations (2019) for the Byzantine Catholic Church of the Resurrection and its Rectory, and with SHPO, for the Hauppauge United Methodist Church and Rural Cemetery (2020).