By Daniel Dunaief

This is part two of a two-part series.

As Erin Brockovich (the real life version and the one played by Julia Roberts in the eponymous movie) discovered, some metals, such as hexavalent chromium can cause cancer in humans.

Environmental exposure to a range of chemicals, such as hexavalent chromium, benzo(a)pyrene, arsenic, and others, individually and in combination, can lead to health problems, including cancer.

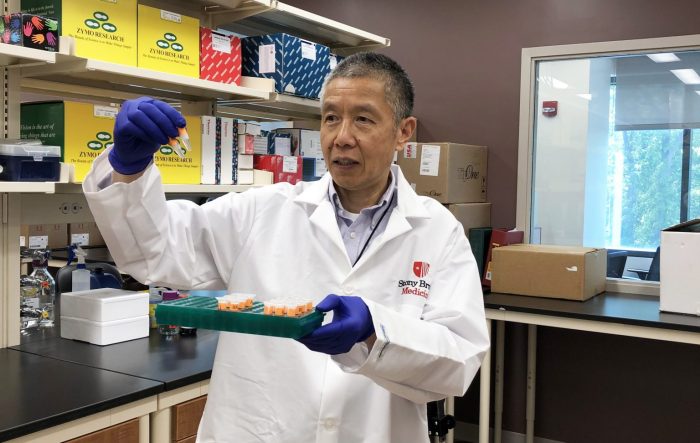

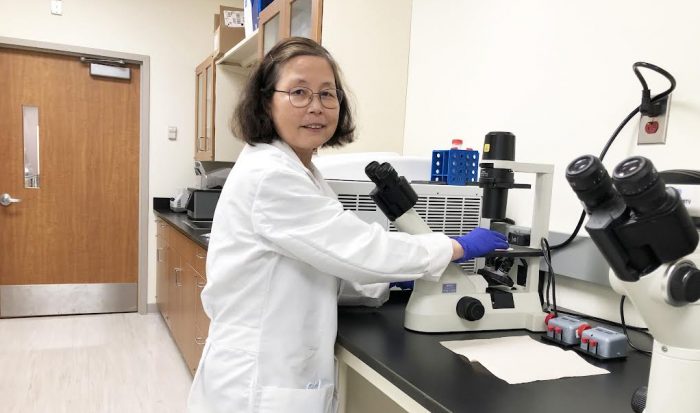

In March, Stony Brook University hired Chengfeng Yang and Zhishan Wang, a husband and wife team to join the Cancer Center and the Pathology Departments from Case Western Reserve University.

The duo, who have their own labs and share equipment, resources and sometimes researchers, are seeking to understand the epigenetic effect exposure to chemicals has on the body. Yang focuses primarily on hexavalent chromium, while Wang works on the mechanism of mixed exposures.

Last week, the TBR News Media highlighted the work of Wang. This week, we feature the work of Yang.

————————————–

When he was young, Chengfeng Yang was using a knife to make a toy for his younger brother. He slipped, cutting his finger so dramatically that he almost lost it. Doctors saved his finger, impressing him with their heroic talent and inspiring him to follow in their footsteps.

Indeed, Yang, who earned an MD and a PhD from Tongji Medical University, is focused not only on answering questions related to cancer, which claimed the life of his mother and other relatives, but also in searching for ways to develop new treatments.

A Professor in the Department of Pathology at the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University and a member of the Stony Brook Cancer Center, Yang has his sights set on combatting cancer.

“Our research always has a significant clinical element,” said Yang. “This is related to our medical background.”

He is interested in studying the mechanism of cancer initiation and progression and would like to develop new strategies for treatment.

Yang and his wife Zhishan Wang recently joined the university from Case Western after a career that included research posts at the University of Pennsylvania, Michigan State University, and the University of Kentucky.

The tandem, who share lab resources and whose research staffs collaborate but also work independently, are focused specifically on the ways exposures to carcinogens in the environment cause epigenetic changes that lead to cancer.

Specifically, Yang is studying how hexavalent chromium, a metal commonly found in the environment in welding, electroplating and even on the double yellow lines in the middle of roads, triggers cancer. It is also commonly used as a pigment to stain animal leather products.

Yang is focused mainly on how long cancer develops after exposure to hexavalent chromium.

People can become exposed to hexavalent chromium, which is also known as chromium 6, through contaminated drinking water, cigarette smoking, car emissions, living near superfund sites and through occupational exposure.

Yang has made important findings in the epigenetic effect of metal exposure. His studies showed that chronic low-level chromium six exposure changed long non-coding RNA expression levels, which contributed to carcinogenesis. Moreover, his studies also showed that chronic low level exposure increased methylation, in which a CH3 group is added to RNA, which also contributed significantly to chromium 6 carcinogenesis.

“It is now clear that metal carcinogens not only modify DNA, but also modify RNA,” Yang explained. Metal carcinogen modification of RNAs is an “exciting and new mechanism” for understanding metal carcinogenesis.

By studying modifications in RNA, researchers may be able to find a biomarker for the disease before cancer develops.

Yang is trying to find some specific epigenetic changes that might occur in response to different pollutants.

Stony Brook attraction

Yang was impressed with the dedication of Stony Brook Pathology Chair Ken Shroyer, whom he described as a “really great physician scientist. His passion in research and leadership in supporting research” helped distinguish Stony Brook, Yang said.

Yang is confident that Stony Brook has the resources he and Wang need to be successful, including core facilities and collaborative opportunities. “This is a very great opportunity for us, with strong support at the university level,” he said.“We plan to be here and stay forever.”

Yang is in the process of setting up his lab, which includes purchasing new equipment and actively recruiting scientists to join his effort.

“We need to reestablish our team,” he said. “Right now, we are trying to finish our current research project.”

He hopes to get new funding for the university in the next two to three years as well. After he establishes his lab at Stony Brook, Yang also plans to seek out collaborative opportunities at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, which is “very strong in RNA biology,” he added.

A return home

Returning to the Empire State brings Yang full circle, back to where his research experience in the United States started. About 23 years ago, his first professional position in the United States was at New York University.

Outside of work, Yang likes to hike and jog. He is looking forward to going to some of Long Island’s many beaches.

He and Wang live in an apartment in South Setauket and are hoping to buy a house in the area. The couple discusses science regularly, including during their jogs.

Working in the same area provides a “huge opportunity” for personal and professional growth, he said.

Yang suggested that his wife usually spends more time training new personnel and solving lab members’ technical issues. He spends more time in the lab with general administrative management and support. Wang has “much stronger molecular biology skills than I have,” Yang explained in an email, whereas he has a solid background in toxicology.

Growing up, Yang said he had an aptitude in math and had dreamed of becoming a software engineer. When he applied to college, he received admission to medical school, which changed his original career path.

Once he started running his own experiments as a researcher, he felt he wanted to improve human health.“Once humans develop disease, in many cases, it’s very expensive to treat and [help] people recover,” he said. “Prevention could be a more cost effective way to improve health.”