Prepared by Malcolm J. Bowman

Charles F. Wurster, professor emeritus of environmental science, School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Stony Brook University, last surviving founding trustee of the Environmental Defense Fund, died on July 6 at the age of 92.

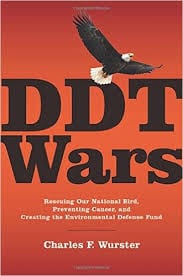

Wurster came to prominence on the issue of the toxic effects of the persistent pesticide DDT on nontarget organisms. During the 1950s and 60s, DDT was used in the mosquito-infested swamps of Vietnam during the war, sprayed on farmer’s crops and impregnated in household fly traps.

A world-class birder, Wurster was concerned with the effects of DDT on birds, ranging from the colorful species of the tropics to the penguins of Antarctica. While a postdoctoral fellow at Dartmouth College in the early 1960s, he gathered robins that had fallen from Dutch elm trees on the campus. In his biochemistry lab, he found their bodies riddled with DDT. The trees had been sprayed to kill the Dutch elm disease.

Of particular concern to Wurster was the concentration of DDT found in birds of prey, including pelicans and raptors, such as the osprey and bald eagle. DDT caused a thinning of eggshells, which led to a catastrophic decline in the osprey reproductive success rate to 2%. The bald eagle was heading toward extinction in the lower 48 states.

In the fall of 1965, Wurster began his academic career as an assistant professor of biological sciences at the newly opened Stony Brook University Marine Sciences Research Center. He gathered 11 colleagues from the university and Brookhaven National Laboratory. In October 1967, for the sum of $37, the group incorporated as a nongovernmental organization in New York State and called it EDF — the Environmental Defense Fund.

Departing from other environmental organization’s approaches, the EDF used the law to ensure environmental justice. The EDF sought the court’s help in halting the application of toxic and lethal chemicals, with a focus on DDT.

After the EDF filed a petition in New York State Supreme Court in Riverhead to halt the spraying of DDT on South Shore wetlands by the Suffolk County Mosquito Commission, a judge in Suffolk County issued a temporary restraining order. Although EDF was later thrown out of court for lack of legal standing, the injunction held.

Under Wurster’s leadership, EDF set up its first headquarters in the attic of the Stony Brook Post Office. This was followed by moving to a 100-year-old farmhouse and barn on Old Town Road in Setauket.

Lacking funding, EDF nonetheless made a bold public step, taking out a half-page ad in The New York Times on March 29, 1970, picturing a lactating Stony Brook mother nursing her baby. Highlighting the concentration of DDT in humans, the text read “that if the mother’s milk was in any other container, it would be banned from crossing state lines!” Funds poured in.

In 1972, following six months of hearings, founding administrator William Ruckelshaus of the Environmental Protection Agency banned the use of DDT nationwide.

EDF rapidly grew into a national organization. Its purview spread into new areas, including litigating against the U.S. Army’s Corps of Engineers dream of completing a cross-Florida sea level shipping canal (1969), removing lead from gasoline and paint (1970-1987) and eliminating polystyrene from fast-food packaging.

Today EDF boasts 12 offices throughout the U.S. and in China, the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Indonesia and Mexico and has three million members and an annual budget of about $300 million. It focuses on environmental justice, protecting oceans and fisheries, sustainable energy and climate change.

In 1995, at Charles Wurster’s retirement from Stony Brook University, Ruckelshaus traveled from Seattle at his own expense to address the campus celebration.

In 2009, Wurster was awarded an honorary degree from Stony Brook University for his seminal contributions to environmental science and advocacy.

Wurster’s enduring leadership and tenacity helped put SBU firmly on the world stage for environmental science, education and advocacy.

Wurster is survived by his two sons Steve and Erik, daughter Nina and his longtime partner Marie Gladwish.

Malcolm J. Bowman is a distinguished service professor emeritus of the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook University. He joined the faculty in 1971 and closely followed the development of EDF for over 50 years, becoming a close associate and personal friend of Charles Wurster.