By Daniel Dunaief

Charging and recharging a battery can cause a strain akin to working constantly without a break. Doctors or nurses who work too long in emergency rooms or drivers who remain on the road too long without walking around a car or truck or stopping for food can function at a lower level and can make mistakes from all the strain.

Batteries have a similar problem, as the process of charging them builds up a structural tension in the cathode that can lead to cracks that reduce their effectiveness.

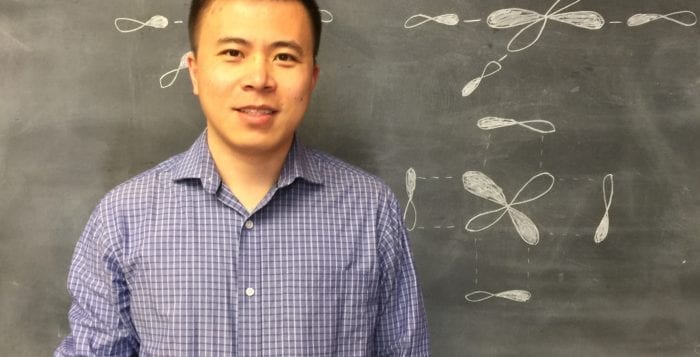

Working with scientists at Brookhaven National Laboratory and the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, Enyuan Hu, an assistant chemist at BNL, has revealed that a doughnut-shaped cathode, with a hole in the middle, is more effective at holding and regenerating charges than a snowball shape, which allows strain to build up and form cracks.

At this point, scientists would still need to conduct additional experiments to determine whether this structure would allow a battery to hold and regenerate a charge more effectively. Nonetheless, the work, which was published in Advanced Functional Materials, has the potential to lead to further advances in battery research.

“The hollow [structure] is more resistant to the stress,” said Hu. Lithium is extracted from the lattice during charging and changes the volume, which can lead to cracks.

The hollow shape has an effective diffusion lens that is shorter than a solid one, he added.

Yijin Liu, a staff scientist at Stanford’s Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) and a collaborator on the project, suggested that the result creates a strategic puzzle for battery manufacture.

Photo from Enyuan Hu

“On the one hand, the hollow particles are less likely to crack,” said Liu. “On the other hand, solid particles exhibit better packing density and, thus, energy density. Our results suggest that careful consideration needs to be carried out to find the optimal balance.” The conventional wisdom about what caused a cathode to become less effective involved the release of oxygen at high voltage, Hu said, adding that this explanation is valid for some materials, but not every one.

Oxygen release initiates the process of structural degradation. This reduces voltage and the ability to build up and release charges. This new experiment, however, may cause researchers to rethink the process. Oxygen is not released from the bulk even though battery efficiency declines. Other possible processes, like loss of electric contact, could cause this.

“In this specific case of nickel-rich layered material, it looks like the crack induced by strain and inhomogeneities is the key,” said Hu.

In the past, scientists had limited knowledge about cracks and homogeneity, or the consistent resilience of the material in the cathode.

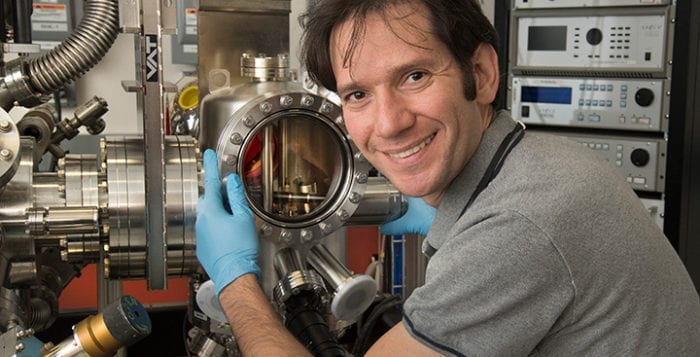

The development of new technology and the ability to work together across the country made this analysis possible. “This work is an excellent example of cross-laboratory collaboration,” said Liu. “We made use of cutting edge techniques available at both BNL and SLAC to collect experimental data with complementary information.”

At this point, Hu estimates that about half the battery community believes oxygen release causes the problem for the cathode, while the other half, which includes Hu, thinks the challenge comes from surface or structural problems.

He has been working to understand this problem for about three years as a part of a five-year study. His role is to explore the role of the cathode, specifically, which is his particular area of expertise.

Hu is a part of a Battery500 project. The goal of the project is to develop lithium-metal batteries that have almost triple the specific energy currently employed in electric vehicles. A successful Battery500 will produce batteries that are smaller, lighter and less expensive than today’s model.

Liu expressed his appreciation for Hu’s contributions to their collaboration and the field, saying Hu “brings more than just excellent expertise in battery science into our collaboration. His enthusiasm and can-do attitude also positively impacts everyone in the team, including several students and postdocs in our group.”

In the bigger picture, Hu would like to understand how lithium travels through a battery. At each stage in a journey that involves diffusing through a cathode, an anode and migrating through the electrolyte, lithium interacts with its neighbors. How it interacts with these neighbors determines how fast it travels.

Finding lithium during these interactions, however, can be even more challenging than searching for Waldo in a large picture, because lithium is small, travels quickly and can alter its journey depending on the structure of the cathode and anode.

Ideally, understanding the journey would lead to more efficient batteries. The obstacles and thresholds a lithium ion needs to cross mirror the ones that Hu sees in everyday life and he believes he needs to circumvent these obstacles to advance in his career.

One of the biggest challenges he faces is his comfort zone. “Sometimes, [comfort zones] prevent us from getting exposed to new things and ideas,” he said. “We have to be constantly motivated by new ideas.”

A cathode expert, Hu has pushed himself to learn more about the anode and the electrolyte.

A resident of Stony Brook, Hu lives with his wife, Yaqian Lin, who is an accountant in Port Jefferson, and their son Daniel, who attends Setauket Elementary School.

Hu and Lin met in China, where their families were close friends. They didn’t know each other growing up in Hefei, which is in the southeast part of the country.

Hu appreciates the support Lin provides, especially in a job that doesn’t have regular hours.

“There are a lot of off-schedule operations and I sometimes need to leave home at 10 p.m. and come back in the early morning because I have an experiment that requires my immediate attention. My wife is very supportive.”

As for his work at BNL, Hu said he “loves doing experiments here. It has given me room for exploring new areas in scientific research.”