By Daniel Dunaief

Popular in late October as Halloween props and the answer to trivia questions about the only flying mammals, bats may also provide clues about something far more significant.

Despite their long lives and a lifestyle that includes living in close social groups, bats tend to be resistant to viruses and cancer, which is a disease that can and does affect other mammals with a longer life span.

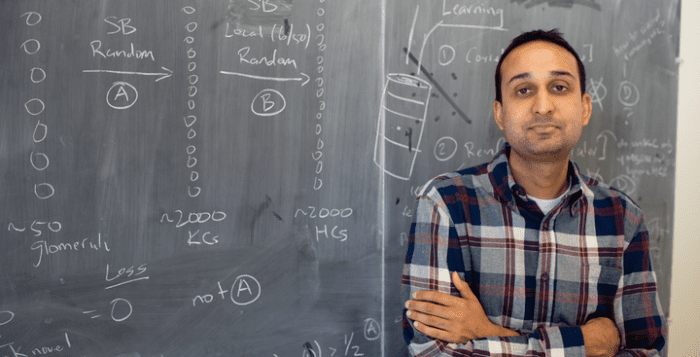

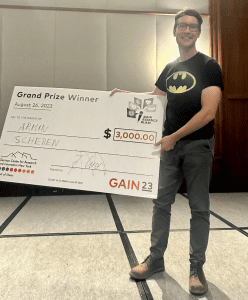

In recent work published in the journal Genome Biology and Evolution, scientists including postdoctoral researcher at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and first author Armin Scheben, CSHL Professor and Chair of the Simons Center for Quantitative Biology Adam Siepel, and CSHL Professor W. Richard McCombie explored the genetics of the Jamaican fruit bat and the Mesoamerican mustached bat.

By comparing the complete genomes for these bats and 13 others to other mammals, including mice, dogs, horses, pigs and humans, these scientists discovered key differences in several genes.

The lower copy number of interferon alpha and higher number of interferon omega, which are inflammatory protein-coding genes, may explain a bat’s resistance to viruses. As for cancer, they discovered that bat genomes have six DNA repair and 33 tumor suppressor genes that show signs of genetic changes.

These differences offer potential future targets for research and, down the road, therapeutic work.

“In the case of bats, we were really interested in the immune system and cancer resistance traits,” said Scheben. “We lined up those genomes with other mammals that didn’t have these traits” to compare them.

Scheben described the work as a “jumping off point for experimental validation that can test whether what we think is true: that having more omega than alpha will develop a more potent anti-viral response.”

Follow up studies

This study provides valuable potential targets that could help explain a bat’s immunological superpowers that will require further studies.

“This work gives us strong hints as to which genes are involved, but fully understanding the molecular biology will require more work” explained Siepel.

In Siepel’s lab, where Scheben has been conducting his postdoctoral research since 2019, he is using human cell lines to see whether adding genetic bat elements makes them more effective in fighting off viral infections and cancer. He plans to do more of this work with mice, testing whether these bat variants help convey the same advantages in live mice.

Siepel and Scheben have discussed improving the comparative analysis by collecting information across bats and other mammals of tissue-specific gene expression and epigenetic marks which would help reveal changes not only in the content of DNA, but also in how genes are being turned on and off in different cell types and tissues. That could allow them to focus more directly on key genes to test in mice or other systems.

Scheben has been collaborating with CSHL Professor Alea Mills, whose lab has “excellent capabilities for doing genome editing in mice,” Scheben said.

Scheben’s PhD thesis advisor at the University of Western Australia, Dave Edwards described his former lab member’s work as “exciting.”

Edwards, who is Director of the UWA Centre for Applied Bioinformatics in the School of Biological Sciences, suggested that Scheben stood out for his “ability to strike up successful collaborations” as well as his willingness to mentor other trainees.

Other possible explanations

While these genetic differences could reveal a molecular biological mechanism that explains the bat’s enviable ability to stave off infections and cancer, researchers have proposed other ways the bat might have developed these virus and cancer fighting assets.

When a bat flies, it raises its body temperature. Viruses likely prefer a normal body temperature to operate optimally.

Bats are “getting fevers without getting infections,” Scheben said.

Additionally, flight increases the creation of reactive oxygen species, which the bat needs to control on an ongoing basis.

At the same time, bats produce fewer inflammatory cytokines, which helps prevent them from having a runaway immune reaction. Some researchers have hypothesized that bats clear reactive oxygen species more effectively than humans.

A ‘eureka’ moment

The process of puzzling together all the pieces of DNA into individual chromosomes took considerable time and effort.

Scheben spent over 280,000 CPU hours chewing through thousands of genes in dozens of species on the CSHL supercomputer called Elzar, named for the chef from the cartoon “Futurama.” Such an effort would have taken eight years on a modern day personal computer.

During this effort, Scheben saw this “stark effect,” he said. “We had known that bats had lost some interferon alpha. What astounded me was that some bats had lost all alpha” while they had also raised interferon omega. That was the moment when he realized he found something novel and bat specific.

Scheben recognized that this finding could be one of many that lead to a better understanding of the processes that lead to cancer.

“We know that it’s unlikely that a single set of genes or a small set of genes such as we identified can fully explain the diversity of outcomes when it comes to a complex disease like cancer,” said Scheben.

A long journey

A resident of Northport, Scheben grew up in Frankfurt, Germany. He moved to London for several years, which explains his use of words like “chuffed” to describe the excitement he felt when he received a postdoctoral research offer at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

When he was young, Scheben was interested in science despite the fact that classes were challenging for him.

“I was pretty poor in math and biology, but I liked doing it,” he said.

Outside of work, Scheben enjoys baking dense, whole wheat German-style bread, which he consumes with cheese or with apple, pear and nuts, and also hiking.

As for his work, which includes collaborating with CSHL Professor Rob Martienssen to study the genomes of plants like maize that make them resilient amid challenging environmental conditions, Scheben suggested it was the “best time to be alive and be a biologist” because of the combination of new data and the computational ability to study and analyze it.

Scheben recognized that graduate students in the future may scoff at this study, as they might be able to compare a wider range of mammalian genomes in a shorter amount of time.

Such a study could include mammals like naked mole rats, whales and elephants, which also have low cancer incidence and long lifespans.