Remembering the Holocaust and 75th Anniversary of Auschwitz Liberation

By Rich Acritelli

This past January marked the 75th anniversary of the Soviet liberation of Auschwitz Extermination Camp in Poland. Like that of the horrific surprise of the American and British military forces that freed the western and central European camps in the spring of 1945, the average Soviet soldier who entered this camp never knew what its main purpose was before they walked into Auschwitz. They unknowingly freed the largest extermination camp that the Germans built some five months before the war ended.

‘Here heaven and earth are on fire

I speak to you as a man, who 50 years and nine days ago had no name, no hope, no future and was known only by his number, A7713

I speak as a Jew who has seen what humanity has done to itself by trying to exterminate an entire people and inflict suffering and humiliation and death on so many others.’

—Auschwitz Survivor and Writer Elie Wiesel

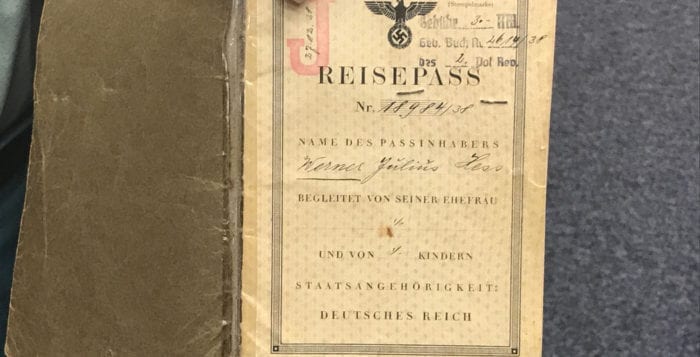

As Auschwitz was not known by most of the Allied combat soldiers, it was understood to be the final stop for many Jews, gypsies, political opposition, homosexuals, Jehovah Witnesses, etc. In 1941, Hitler began to authorize the deportation of the Jews to Poland. While Germany had its own concentration camp system, the later killings of Jews and other “enemies of the state,” took place mostly in the east. As the German military continued to show its dominance against every nation that it fought against, more Jews came under their control. Although the Nazis always needed additional workers, they did not provide any decency to those groups that were deemed to be “inferior” populations against the German Reich.

The SS, under the direction of Heinrich Himmler, was determined to capture and kill every Jew in Europe. Most of these plans were to be carried out at Auschwitz, which was located 50 miles southwest of Krakow. This western area of Poland was originally known as Oswiecim, a sparsely populated town that had 12,000 citizens and included some 5,000 Jews. At first, this camp was created to handle the flow of Polish prisoners of war and partisans who opposed this German occupation. During the Jan. 20, 1942, Wannsee Conference that was chaired by SS leader Reinhard Heydrich and representatives of 15 departments of the German government, they met to decide the final fate of the “Jewish Question,” which resided within their conquered territories.

Heydrich, who was later killed by Czechoslovakian-British commandos, was the driving force to carry out the orders of Hitler and Himmler to transport and kill the estimated 11 million Jews in Europe. He worked with the bureaucracy of his government to ensure that there would be enough resources and logistics to follow Hitler’s directives to destroy these self-proclaimed enemies of the regime.

Auschwitz was established for this exact purpose. Even through the massive fighting that Germans had to wage on every front, Hitler demanded that his orders of the “Final Solution” were to be followed through the creation of other smaller centers at Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka. The first victims at Auschwitz were 850 Soviet military political prisoners of war that were killed by Zyklon B gas. This chemical was primarily used to deter rodents and it later was utilized by the SS to kill almost one million people at Auschwitz.

This massive area constructed by Germany was broken into two separate places for the prisoners. Birkenau held most of the gas chambers and crematoriums for those people that were selected right away for death. The other portions of Auschwitz were built for massive slave labor where their prisoners worked within factories established inside and outside of this camp. As some were chosen to live, the Germans calculated the minimum number of calories that were needed to survive. These people were expected to eventually die from the spring of 1942 to the fall of 1944. People from all over the German-occupied land, ranging from France on the Atlantic Ocean to the Greek islands in the Aegean Sea, were deported to Auschwitz.

By the end of the war, when Hitler was all but assured that the Allies would defeat his armies, the killing continued at a faster rate against the Hungarian Jews. This was one of the few Jewish populations that were still protected by their own government. But after a regime change that supported the Nazis, many Jews were deported right away to Auschwitz. Adolph Eichmann, who was later captured by Israeli agents in Argentina in 1961, was driven to capture as many Hungarian Jews and deport them to their death. Swedish diplomat Raul Wallenberg was sent to Hungary through the indirect support of the United States. When it became apparent that the Germans would not stop, this was a last-ditch attempt to save these Eastern European Jews who were not yet targeted by the Nazis.

Wallenberg bribed Hungarian officials and issued Swedish passes that made these Jews citizens of his nation. Even as he was engaged within this vital humanitarian mission, Wallenberg met with the Soviet military after they liberated Hungary. The diplomat, who regularly risked his own life, was believed to be an American spy by the Soviet KGB. Wallenberg was taken by the Soviets and never seen again.

A main question that people have pondered since 1945 is why the Allies did not do more to limit the extent of the Holocaust. Around the clock, American and British bombers targeted every military and industrial location in Germany. Auschwitz was located near the eastern part of Germany and it was within the range of Allied aircraft that operated from English, Italian and later French military bases. Early in the war, when evidence was sent to Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, they initially refused to believe that the Germans were committing wide-scale mass murder. But as the war continued, increased stories emerged from the people who escaped from the death camps looked to identify to the world the true intentions of Hitler.

When it was completely proven to Roosevelt and Churchill that the Germans would never halt this policy, the Western Allied leaders did little to stop this genocidal policy. Since 1945, many of the inmates of Auschwitz openly stated that they would rather have died from aerial bombs seeking to destroy this factory of death than by being personally led to the gas chambers. Information was smuggled out of Auschwitz that described the location of the railroad lines, gas chambers and crematoriums that were later analyzed by Allied leaders. Both Roosevelt and Churchill believed that the only way to end the Holocaust was not to divert any major resources from quickly winning the war. The issue with this policy was that there was not even a limited effort to thwart the carrying out of the Holocaust.

Captain Witold Pilecki was a Catholic Polish cavalry officer who gathered intelligence for his government. The Polish were in hiding after their country was taken over by the Germans. When rumors continued to circulate about the true intentions of Auschwitz, he volunteered to purposely get arrested and be sent to the camp. He spent almost two years at Auschwitz, where he smuggled out reports that were read by western leaders. Pilecki organized the under-ground resistance efforts to possibly take over the camp. He believed that if this facility was attacked from the outside by either the Polish resistance or the Allies, that his men were able to control the interior from the Germans. When he realized that help was not coming, Pilecki escaped from Auschwitz. He later fought against the Nazis and was again taken as a prisoner, but he survived the war. After Poland was liberated, he returned home to oppose the communists, and he was later killed by his own government as being an accused spy that supported the democratic government that was in exile in England.

At the end of the war, as American forces were destroying the German army on the Western Front, additional camps were discovered by the U.S. military. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, along with generals Omar N. Bradley and George S. Patton, were sickened at the sight of Hitler’s “Final Solution” in Western Europe. Under the orders of Eisenhower, he directed large parts of his army to personally observe camps like Berga, Dachau, Mauthausen and Ohrdruf. It was his belief that current and future people would deny the existence and purpose of this organized terror. Today, as many Holocaust survivors are well into their 90s, they fear that resentment is at heightened levels toward many different religious and ethnic groups. And like the concerns that Eisenhower presented some 75 years ago, many of these survivors believe that the lessons of the Holocaust are being forgotten, and that there are more Holocaust deniers around the world who seek to suppress the knowledge of these crimes against humanity.

Rich Acritelli is a social studies teacher at Rocky Point High School and an adjunct professor of American history at Suffolk County Community College.