Life Lines: Five books that shaped my life

By Elof Axel Carlson

Occasionally, I read an item on Facebook that engages my attention. One item asked several celebrities (like successful billionaires) to list the five books they most enjoyed reading and briefly tell why they were important. Here are my five favorite books:

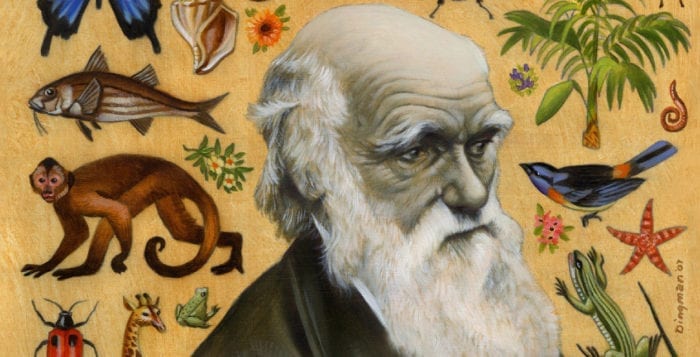

‘Civilization and Its Discontents’ by Sigmund Freud

Freud introduces the source of the tensions between creativity and destructiveness. He assigns it to the id/superego conflict. I would use instead our capacity for love, empathy and sympathy versus our capacity for hate, bigotry and violence. Freud calls the process sublimation. He began writing this book in 1929 and published it two years later. He predicted that the rise of Nazism was imminent and would lead to massive death because humanity does not know how to sublimate its discontents into the path of the joys of civilization — its arts, humanity, play and immense scholarship.

Freud introduces the source of the tensions between creativity and destructiveness. He assigns it to the id/superego conflict. I would use instead our capacity for love, empathy and sympathy versus our capacity for hate, bigotry and violence. Freud calls the process sublimation. He began writing this book in 1929 and published it two years later. He predicted that the rise of Nazism was imminent and would lead to massive death because humanity does not know how to sublimate its discontents into the path of the joys of civilization — its arts, humanity, play and immense scholarship.

‘Jean Barois’ by Roger Martin du Gard

This is my favorite novel. It is the story of a young French boy raised by a devout Catholic family who thinks he will become a priest. He discovers instead that the more he learns the more doubts arise not only about his calling but his faith. He teaches biology and is fired for teaching evolution. His wife and daughter separate from him. He throws himself into the Freethinkers movement in France and gets involved in the Dreyfus case. He discovers that reason alone cannot sustain his life but returning to his faith is equally inadequate.

This is my favorite novel. It is the story of a young French boy raised by a devout Catholic family who thinks he will become a priest. He discovers instead that the more he learns the more doubts arise not only about his calling but his faith. He teaches biology and is fired for teaching evolution. His wife and daughter separate from him. He throws himself into the Freethinkers movement in France and gets involved in the Dreyfus case. He discovers that reason alone cannot sustain his life but returning to his faith is equally inadequate.

‘The Essays of Michel de Montaigne’

Montaigne’s essays describe his life and the times in which he lived in the context of a rich appreciation of classical literature. He tries to make sense of a world that is pretentious, at war with itself and filled with irony, contradictions and lessons we can extract from the past. Read a 20th-century translation of these essays rather than the 16th-century English translation. Start with his essay on friendship and his essay: “How by various means we all end at the same place.”

Montaigne’s essays describe his life and the times in which he lived in the context of a rich appreciation of classical literature. He tries to make sense of a world that is pretentious, at war with itself and filled with irony, contradictions and lessons we can extract from the past. Read a 20th-century translation of these essays rather than the 16th-century English translation. Start with his essay on friendship and his essay: “How by various means we all end at the same place.”

‘The Diary of Samuel Pepys’

I loved reading Pepys’s diaries and was thrilled that he was an eyewitness to the bubonic plague that swept through England in 1665 and the London fire that destroyed most of the city in 1666. Pepys is an imperfect person — not immune to accepting sacks of gold for awarding contracts for the British Navy, flirting with other women but loving his wife and learning to avoid threats to his career from others drawn to the politics of the time.

I loved reading Pepys’s diaries and was thrilled that he was an eyewitness to the bubonic plague that swept through England in 1665 and the London fire that destroyed most of the city in 1666. Pepys is an imperfect person — not immune to accepting sacks of gold for awarding contracts for the British Navy, flirting with other women but loving his wife and learning to avoid threats to his career from others drawn to the politics of the time.

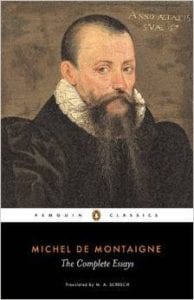

‘The Origin of Species’ by Charles Darwin

Darwin is an excellent observer and narrator. He wrote this book as an abstract of a huge multivolume plan for presenting his theory of evolution of species by natural selection. He is careful to distinguish evidence from theory and uses the facts to derive his interpretations of how evolution works. Darwin did not start with a theory and then seek facts to support it. He went with no idea about evolution and instead allowed the hundreds of observations and findings guide him to the only interpretation that made sense of the relations he found whether it was the work of hobbyists and breeders creating new varieties of plants and animals, the geographic distribution of plants and animals he encountered in his trip around the world, or the fossils he encountered.

Darwin is an excellent observer and narrator. He wrote this book as an abstract of a huge multivolume plan for presenting his theory of evolution of species by natural selection. He is careful to distinguish evidence from theory and uses the facts to derive his interpretations of how evolution works. Darwin did not start with a theory and then seek facts to support it. He went with no idea about evolution and instead allowed the hundreds of observations and findings guide him to the only interpretation that made sense of the relations he found whether it was the work of hobbyists and breeders creating new varieties of plants and animals, the geographic distribution of plants and animals he encountered in his trip around the world, or the fossils he encountered.

——————————————————————————————————————————

I have learned to sublimate my discontents and have had 14 books published for which I thank Freud. I find Jean Barois to be the finest writing on the conflict between science and belief, science and politics and the difficulty of finding a life that sustains us. Montaigne taught me that in difficult times, we can find many things to avoid and how diverse the world is for each new generation that emerges. I have kept a diary (now 112 volumes) more years than not since I first read Pepys’s diary in 1949. Darwin’s book taught me how to use a Baconian approach to science, letting the data amass and allowing an unbiased mind to connect the dots that make new findings and interpretations possible.

Elof Axel Carlson is a distinguished teaching professor emeritus in the Department of Biochemistry and Cell Biology at Stony Brook University.