By Daniel Dunaief

Even the name Tyrannosaurus rex seems capable of causing ripples across a glass of water, much the way the fictional and reincarnated version of the predator did in the movie “Jurassic Park.”

Long before the predatory dinosaur roamed North America with its powerful jaws and short forelimbs, some of its ancestral precursors, whom scientists believed were considerably smaller, remained a mystery.

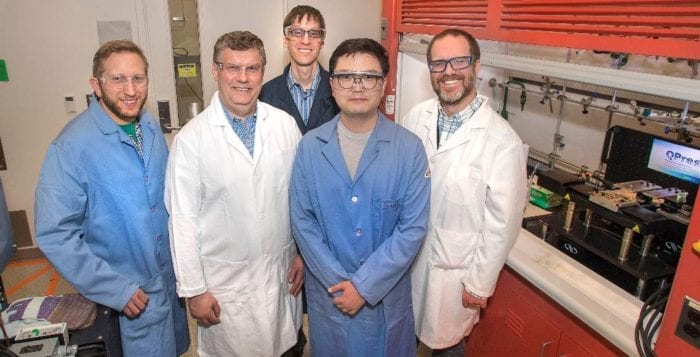

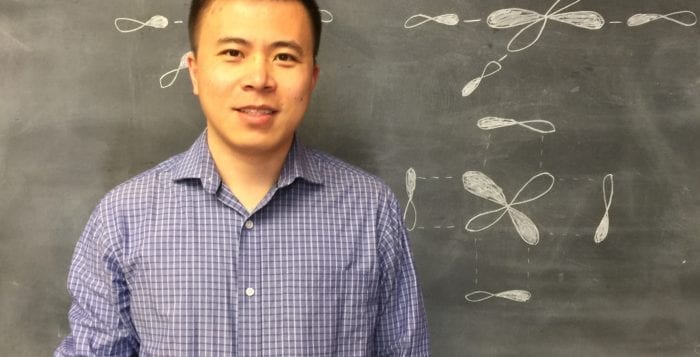

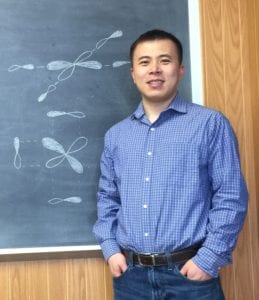

A team of scientists led by Sterling Nesbitt, an assistant professor at Virginia Tech, shed some light on a period in which researchers have found relatively few fossils when they shared details about bones from two members of T. rex’s extended ancestral family in New Mexico.

These fossils, which they named Suskityrannus hazelae, help fill in the record of tyrannosauroid dinosaurs that lived between the Early Cretaceous and latest Cretaceous species, which includes T. rex.

The researchers, which included Alan Turner, an associate professor of anatomical sciences at Stony Brook University, chronicled the history of these fossils from the Late Cretaceous period, or about 92 million years ago.

“Getting a chance to understand the origin of something is compelling,” said Turner. “Having a discovery like Suskityrannus, which helps us understand how the body plan of tyrannosauroids evolved, is super interesting.” The fossils reveal the “humble beginnings” of a group that would “later dominate North American terrestrial ecosystems.”

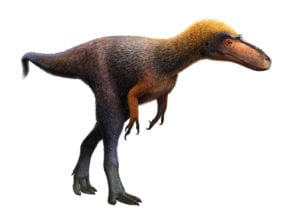

Indeed, the new dinosaur was considerably more modest in size than future predators. The Suskityrannus, which included one individual that wasn’t fully grown when it died after living at least three years, measured about three feet at the hip, weighed about 100 pounds, and was about nine feet long, which made it more like a full grown male wolf, albeit longer because of its extended tail.

Scientists had found earlier tyrannosaur relatives from the Early Cretaceous as well as T. rex and its closest relatives near the end of the Late Cretaceous. They were missing data about tyrannosaurs from the middle of the group’s history because fossils from this time period are so rare.

The researchers cautioned that this paper, which was published in the journal Nature, Ecology & Evolution, does not suggest that Suskityrannus was a direct ancestor of T. rex. It does, however, fill a fossil gap in the extended T. rex family.

The Suskityrannus species has a broad mouth and a muscular skull. Additionally, the bones in its foot were built in a way that made it good at absorbing shocks.

As far as fossil specimens, the bones from this finding are “well represented” across various parts of this creature’s anatomy, including a “lot of limb anatomy and a good portion of the skull and vertebral column,” Turner said.

This collection of bones help define where on the evolutionary map this new species belong. Some of the anatomical characteristics in this new species appear to be well-suited for future predators, even as they likely also provided an adaptive advantage for the Suskityrannus.

“These are features that were already in place much earlier” than this new species needed them, Turner said. They may have been adaptations that helped with their agility or with the environment in which they lived. Eventually, evolution turned them into the kinds of anatomical features that made them useful when T. rex eventually grew to as large as 16 tons.

“That’s something you see often in evolution: the way a species is using [its anatomy] isn’t always necessarily what the features evolved for,” Turner said. “Evolution can only work with what it has. What we see with Suskityrannus is that it had these things that became important later on.”

Turner’s role was to help compile and analyze the enormous amount of data that came out of this discovery. He explored how the number of species changed along the boundary between the first half of the Late Cretaceous and the second half of the Late Cretaceous periods, adding that the process of exploring and analyzing such a discovery can take years.

Indeed, Turner first saw the fossil in 2007. “The studies take a long time and you can get lost in the details,” he said. “You do try and keep the big picture in your head. That’s the thing that makes [the work] interesting.”

Turner became a part of this work through his connection to Nesbitt. The two scientists attended graduate school together at Columbia University. They have been doing field work together since 2005.

Nesbitt explained in an email that he thought of including Turner immediately “because he is an expert on aspects of paleobiology and theropods, plus he is an excellent colleague to work on papers with.”

In the research paper, the scientists have created an artistic rendering of what this new species might have looked like. While Turner acknowledges that the image involves a “bit of an artistic license,” the image is also “bound by what we know.”

Nesbitt said this finding provides information about the theropods as a whole. “We really don’t know why T. rex and its closest relatives got so big,” he said, but researchers do know this happened at the end of the Cretaceous period, after 80 million years of being relatively small.

Turner lives in Port Jefferson with his wife, Melissa Cohen, who is the graduate program coordinator in the Department of Ecology & Evolution at Stony Brook University. The couple has two children.

Turner, who grew up in a suburb of Cleveland, recalls a field trip when he was 17 that encouraged him to pursue a career in paleontology. He was conducting research in Montana and he was exploring dinosaurs and sharing a sense of camaraderie with others on the expedition.

“I remember feeling like that was an affirming experience,” Turner said.

As for the discovery of Suskityrannus, Turner shared the wonder at finding a new species, something he’s been a part of eight times with dinosaurs in a career that now includes 11 years at Stony Brook.

“It’s always pretty exciting when you get to work on something that’s new,” he said.