Help preserve history! The Port Jefferson Village Archive department, located on the second floor of the Village Center, 101A East Broadway, is seeking old photos of Port Jefferson from the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. Photos will be returned after they have been scanned. For additional details, call Chris Ryon at 631-802-2165.

Book Review: ‘While There’s Life …’

‘Surviving one more day in the camps was spiritual resistance.’

Reviewed by Jeffrey Sanzel

Ruth Minsky Sender’s three memoirs — “The Cage,” “To Life” and “The Holocaust Lady” — are must-reads. The books chronicle the author’s life in Europe, from before World War II, through her inhumane imprisonment in the Nazi concentration camp system, and beyond. Sender is a writer of exceptional ability: vivid, introspective and yet always accessible. I have seen her speak and she is every bit as strong and present in person as she is on the page.

Now, the East Setauket resident has a new and unusual offering, a book of poetry, with the majority of poems written while she was in the Mittelsteine Labor Camp (1944–1945). Translated from the Yiddish by Rebecca Wolpe, the poems are raw and disturbing — as they should be. But underneath many of them is her mother’s motto: “While there’s life … there is hope.”

Miriam Trinh’s well-thought-out introduction shows the importance of “Jewish poetic creativity during the Holocaust as a reaction to Nazi oppression, persecution, and annihilation,” giving context to the writing as well as insight into Sender’s work. “This poetry,” writes Trinh, “was a direct reaction to her experiences during and after the Holocaust: the loss of her prewar identity, the realization that this loss was permanent and unrecoverable and the need to construct a new, postwar identity.”

In addition to the works written while she was in the camp, there are a handful of poems that were created in the 1950s and later. They are equally as important but are taken from a different perspective. All but two of the poems were written in Yiddish (those two in Polish), first on scraps of brown paper bags stolen from the garbage, later in notebooks.

She writes, “These poems were written in little notebooks while I was incarcerated in the Nazi slave labor camp in Mittelsteine, Germany, as prisoner #55082. I wrote them while hiding in my bunk. Every Sunday, I would read them aloud to the fifty other women living with me in the room. They were my critical and faithful audience. I endeavored both to depict scenes from our life and to give everyone a little courage and the will to continue. This was how we spent our Sundays, and anyone who had bit of talent did her best to bring a little happiness into our tragic lives.”

The notebook was given to her by the Nazi commandant after the girls were forced to perform at Christmas. They were told if they didn’t perform, all 400 Jewish girls would be punished. Sender read two of her poems (“My Work Place” and “A Message for Mama”) and somehow they touched the cold-hearted, pitiless Nazi commandant who presented her with the first book to record her verses.

Each poem is a delicate work of art. Some are a dozen lines, while others run to several pages. Given the cruel nature of the subject, it is difficult to comment. Needless to say, they are all vividly descriptive and fiercely honest.

“My Friend” explains the importance of writing. “Our Day” is a single day in the camp, from dreaming to sundown, and shows, even in the brutality, the glimmer of hope. “Greetings from Afar” addresses the day-to-day evil and sadism the prisoners relentlessly faced every moment. “Separation” expresses the pain of being split from her brothers. In “At Work,” the language depicts the harshness of the factory; in the clipped lines you can hear the merciless grinding of the machines.

“A Ray of Light” is just that: the courage to aspire to liberation in the midst of misery. “The Future,” one of the most complicated, looks at liberation from a different aspect: what will become of them and, even more so, where will their anger go upon being freed? It is a breath-taking piece.

“We Need Not Their Tears” faces the issue of where to go when returning to your home is a deadly option. “Where Is Justice?” is offered in two versions: one composed in the camp and the other written many years after. Both are the horrific story of a prisoner forced to beat another prisoner, driving the girl mad. In a book of challenging pieces, it is one of the most unsettling and haunting.

A later poem (1955), “Teaching Children Yiddish” is a celebration of the language that still exists, a symbol of persistence, with education being at its heart.

“While There’s Life …” is a volume that should be read and re-read by people of all faiths. It is a portrait not just of survival but of how one woman transformed her pain in humanity’s darkest hour into art … into life.

To order your copy of ‘While There’s Life …’ visit www.yadvashem.org and choose the Shop icon.

TBR News Media hosts screening of ‘One Life to Give’

By Heidi Sutton

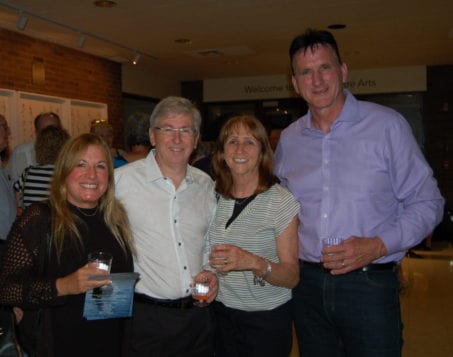

The 1,000-seat theater at Stony Brook University’s Staller Center was filled to capacity last Sunday night as the community came out in droves to celebrate the first screening of TBR News Media’s feature-length film, “One Life to Give.” And what a celebration it was.

“I have to say this exceeds our highest expectations. We are so thrilled,” said TBR News Media publisher Leah Dunaief, scanning the packed house as she welcomed the audience to “what has been a year’s adventure.”

“I am privileged to be the publisher of six hometown papers, a website, a Facebook page and, now, executive producer of a movie,” she beamed.

Dunaief set the stage for what would be a wonderful evening. “I’m inviting you now to leave behind politics and current affairs and come with me back in time more than two centuries to the earliest days of the beginning of our country — the start of the American Revolution.”

“We live in the cradle of history and I hope that when you leave tonight you will feel an immense pride in coming from this area,” she continued. “The people who lived here some 240 years ago were people just like us. They were looking to have a good life, they were looking to raise their children.” Instead, according to Dunaief, they found themselves occupied by the British under King George III for the longest period of time.

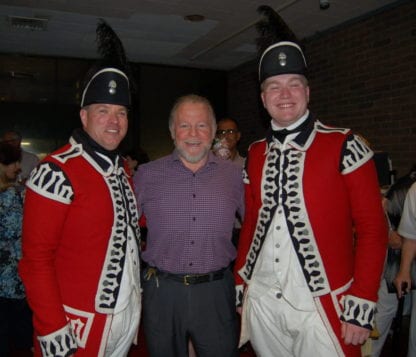

Filmed entirely on location on the North Shore in 16 days, the film tells the story of schoolteacher turned spy Nathan Hale and how his capture and ultimate death by hanging in 1776 at the age of 21 led to the development of an elaborate spy ring in Setauket — the Culper spies — in an effort to help Gen. George Washington win the Revolutionary War.

Scenes were shot on location at Benner’s Farm in East Setauket, the William Miller House in Miller Place, the Sherwood-Jayne Farm, Thompson House and Caroline Church of Brookhaven in Setauket and East Beach in Port Jefferson with many local actors and extras, period costumes by Nan Guzzetta, props from “TURN” and a wonderful score by Mark Orton.

The film screening was preceded by a short behind-the-scenes documentary and was followed by a Q&A with Dunaief, producer and writer Michael Tessler and director and writer Benji Dunaief along with several key actors in the film — Dave Morrissey Jr. (Benjamin Tallmadge), Hans Paul Hendrickson (Nathan Hale), Jonathan Rabeno (John Chester) and David Gianopoulos (Gen. George Washington).

“It says quite a bit about our community that we could pack the Staller Center for a story that took place over two hundred years ago,” said Tessler, who grew up in Port Jefferson. “I hope everyone leaves the theater today thinking about these heroes — these ordinary residents of our community who went on to do some extraordinary things and made it so that we all have the luxury to sit here today and enjoy this show and the many freedoms that come with being an American.”

Director Benji Dunaief thanked the cast, crew and entire community for all their support. “In the beginning of this project I did not think we would be able to do a feature film, let alone a period piece. They say it takes a village, but I guess it actually takes three.”

“Our cast … threw themselves 100 percent into trying to embody these characters, they learned as much as they could and were open to everything that was thrown at them — I’m blown away by this cast. They are just incredible,” he added.

“The positivity that was brought to the set every day made you really want to be in that environment,” said Rabeno, who said he was humbled to be there, and he was quick to thank all of the reenactors who helped the actors with their roles.

One of the more famous actors on the stage, Gianopoulos (“Air Force One”) was so impressed with the way the production was handled and often stopped by on his day off just to observe the camera shots. “I really enjoyed just watching and being an observer,” he said, adding “It was just such an honor [to be a part of the film] and to come back to Stony Brook and Setauket where I used to run around as a little kid and then to bring this story to life is just amazing.”

According to the director, the film has been making the rounds and was recently nominated for three awards at Emerson College’s prestigious Film Festival, the EVVY Awards, including Best Editing, Best Writing and Best Single Camera Direction and won for the last category.

Reached after the screening, Assemblyman Steve Englebright (D-Setauket) said the film was the essence of a sense of place. “I thought it was spectacular. I thought that it was one of the highlights of all of the years that I have lived in this community.”

He continued, “It all came together with local people and local places talking about our local history that changed the world and the fact that it was on the Staller Stage here at a public university that was made possible by the heroics of the people who were in the film both as actors today and the people that they portrayed.”

For those who missed last Sunday’s screening, the film will be shown again at the Long Island International Film Expo in Bellmore on July 18 from 2 to 4 p.m.

Filming for a sequel, tentatively titled “Traitor,” the story of John André who was a British Army officer hanged as a spy by the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, will begin in two weeks.

Special thanks to Gold Coast Bank, Holiday Inn Express, Island Federal Savings Bank and Stony Brook University for making the evening’s screening possible.

Photos by Heidi Sutton and Rita J. Egan

Reflecting on those who made America’s independence possible

By Beverly C. Tyler

As we prepare to celebrate Independence Day, July 4, it is fitting to reflect on the actions of some of the men and women who helped win our independence.

The Revolutionary War had a great effect on the residents of Long Island. After the Declaration of Independence was signed July 4, 1776, many Long Islanders, especially in Suffolk County, received it enthusiastically. Their enthusiasm was short-lived, however, for on Aug. 27, 1776, the British took possession of New York City, following the Battle of Long Island in Brooklyn, and with its possession of all of Long Island. The residents were to be under British control for the next seven years.

“Since my arrival at camp I have had as large an allowance of fighting as I could, in a serious mood, wish for.”

— Benjamin Tallmadge

A large number of Long Island Patriots fled to Connecticut and became refugees, giving up their lands, homes and most of their possessions. Those who stayed lived under often harsh, military rule. The residents were forced to provide whatever His Majesty’s forces needed. Cattle, feed, grains, food, wagons and horses, especially cordwood for fuel was taken, and in most cases, not paid for. Long Island was virtually stripped of its mature trees during the first three to five years of the war to supply lumber and fuel for New York City.

In addition to suffering at the hands of the British, many Long Islanders were also considered fair game by their former friends and neighbors in Connecticut who would cross the Sound to harass the British, steal supplies, destroy material the British might use and take captives. The captives were often taken in exchange for the Patriots captured by the British.

Benjamin Tallmadge, Gen. George Washington’s chief of intelligence from the summer of 1778 until the end of the Revolutionary War, was born and spent his youth in Setauket, Long Island. Following four years at Yale College in New Haven and a year teaching in Wethersfield, Connecticut, Tallmadge joined the Continental Army. He took an active part in the Battle of Brooklyn and progressed rapidly in rank. As a captain in the 2nd Regiment of Continental Light Dragoons — Washington’s first fast attack force mounted on horses — Tallmadge came under Washington’s notice. By December of 1776, Washington had asked Tallmadge, in addition to his dragoon responsibilities, to gather intelligence from various spies on Long Island. In 1777 Tallmadge coordinated and received intelligence from individual spies on Long Island. (See History Close at Hand article published in The Village Times Herald May 10 edition.)

Tallmadge was promoted to the rank of major April 7, 1777. In June Tallmadge’s troop, composed entirely of dapple gray horses, left their base at Litchfield, Connecticut, and proceeded to New Jersey where Washington reviewed the detachment and complimented Tallmadge on the appearance of his horsemen.

Washington gave the troops of the 2nd Regiment little chance to rest after they came to headquarters, and Tallmadge wrote, “Since my arrival at camp I have had as large an allowance of fighting as I could, in a serious mood, wish for.”

In September and October, Tallmadge took part in the Battle of Germantown. In November of 1777, when the American army finally went into winter quarters at Valley Forge, Tallmadge was ordered, “with a respectable detachment of dragoons,” to act as an advance corps of observation.

During these maneuvers into the no-mans-land area between the American and British lines around Philadelphia, Tallmadge again engaged in obtaining intelligence of the enemy’s movements and plans.

In January of 1778, the 2nd Regiment of Light Dragoons was ordered to Trenton, New Jersey, where the other cavalry regiments were assembling to spend the winter. Throughout the spring, Tallmadge waited for action. In June the 2nd Regiment was assigned to take up a position in advance of the American lines near Dobbs Ferry. In July Washington returned to the Hudson Valley with most of his army. With the arrival of the French fleet under Count d’Estaing in July, the pressing need for organized military intelligence could no longer be avoided. Officers, and especially dragoon officers, were encouraged to find intelligent correspondents who could furnish reliable information to American headquarters.

During the summer of 1778, Tallmadge was able to establish, with Washington’s approval, a chain of American spies on Long Island and in New York, the now recognized Culper Spy Ring, feeding information through Setauket, across Long Island Sound to Fairfield, Connecticut, and by mounted dragoon to Washington’s headquarters. Despite Tallmadge’s important role in the formation of the spying operation, his duties as field officer of the 2nd Regiment took most of his time during the summer and fall of 1778. The men and women who made the spy ring function lived in constant danger in both British and Patriot territory. We owe them the greatest respect and honor we can offer, especially on July 4.

Beverly C. Tyler is Three Village Historical Society historian and author of books available from the society at 93 North Country Road, Setauket. For more information, call 631-751-3730 or visit www.tvhs.org.

TBR News Media presents film screening of ‘One Life to Give’

Film showcased at SBU’s Staller Center for the Arts

By Talia Amorosano

The wait is over. On Sunday, June 24, an integral piece of U.S. and Long Island history will be revisited in the geographic location where much of it actually took place. At 7 p.m., the Stony Brook University’s Staller Center for the Arts, 100 Nicolls Road, Stony Brook, will host the first major public screening of “One Life to Give,” a film about the friendship and lives of young American heroes Benjamin Tallmadge and Nathan Hale, whose actions would lead to the creation of a Revolutionary spy ring based on the North Shore of Long Island.

Presented in the Main Theater, doors will open at 6:45 p.m. After a message from publisher Leah Dunaief, a short behind-the-scenes documentary will be shown followed by the main film screening. After a message from the creators, the evening will conclude with a Q&A with the cast and crew. Admission to the event is free, courtesy of TBR News Media. No reservations are necessary.

The film’s co-producer and writer, Michael Tessler, describes the film as an exploration of historical events with a human focus. “After spending several years researching Benjamin Tallmadge and the other heroes featured in our film, I began to look at them not as detached names in a textbook, but more so as real people, with real stories that deserve to be told,” he said.

Dave Morrissey, the actor who portrays Tallmadge in the film, describes his character as a “22-year-old kid,” who, despite his relative youth, is “focused” and “grounded,” propelled into action by the death of his brother at the hands of the British. “When something like that happens to you, you turn into a machine … into something else,” said Morrissey. “If you channel the energy and do what’s right, the possibilities are endless.”

By focusing a metaphorical macro lens on the multidimensional characters of Tallmadge and Hale, the film traverses consequential moments of American history: the Battle of Long Island, the anointing of America’s first spy and the events that would lead to the creation of the Culper Spy Ring, a group of men and women who risked their lives and status to gather British intelligence for the Revolutionary cause.

Though Tessler notes that the film is, at its heart, a drama, he and the film’s director and co-producer Benji Dunaief stress the cast and crew’s commitment to accuracy in their interpretation of historical events.

“The history comes second to the narrative in most [other film adaptations of historical events],” says Dunaief. “Our approach with this film was the exact opposite. We wanted to see where we could find narrative within [pre-existing] history.”

“Many of the lines from the film were plucked directly from the diaries of the heroes themselves,” stated Tessler. “We worked closely with historians and Revolutionary War experts to achieve a level of accuracy usually unseen in such a local production.”

The fact that many scenes from the film were shot in the locations where the events of the real-life narrative took place helped give the visuals a sense of truthfulness and the actors a sense of purpose.

“The location took production to the next level. It’s really crazy how closely related the sets we used were to the actual history,” said Dunaief, who specifically recalls filming at a house that contained wood from Tallmadge’s actual home. “It helped to inspire people in the cast to get into character.”

Morrissey recalls spending a particularly inspiring Fourth of July on Benner’s Farm in East Setauket. “We were filming the war scenes with all the reenactors … in the cabin that we built for the set … in the town where the battles and espionage had really happened. There were fireworks going on in the background while we sang shanty songs. It was amazing.”

Though locational and historical accuracy played a large role in making filming a success, ultimately, Dunaief and Tessler credit the resonance of “One Life to Give” to an engaged and participatory community. “This was a community effort on all accounts,” says Dunaief, noting the roles that the Benners, Preservation Long Island, The Ward Melville Heritage Organization, the Three Village Historical Society and others played to bring “One Life to Give” to fruition.

The fact that the screening will take place at the Staller Center, in the heart of the community that helped bring the film about, represents a full-circle moment for the cast and crew. “We’re calling it a screening but it is so much more,” said Dunaief. “It is a fantastic example of how the community has stood by this film, from beginning to end.”

“We’re beyond honored and humbled to use a screen that has seen some of the greatest independent films in history,” said Tessler. “Stony Brook University has been a wonderful partner and extremely accommodating as we work to bring our local history to life.”

Tessler projects confidence that viewers will leave the screening with a similar sense of gratitude. “This story shows a part of our history that I think will make the audience very proud of the place they call home.”

The future of ‘One Life to Give’:

Michael Tessler and Benji Dunaief plan to show the film at festivals around the country, to conduct a series of screenings on Long Island, and to partner with local historical societies that can use it as an educational tool. Additionally, a sequel to “One Life to Give,” titled “Traitor,” is already in the works. Filming will begin this summer.

All photos by Michael Pawluk Photography

Port Jeff Army Navy owners retiring, closing uptown location in family for 80 years

Boarding the wrong train in 1939 might have put a damper on Joseph Sabatino’s day, but if he knew the series of events that would play out over the eight decades that followed, what he likely viewed as a

mistake would be more accurately depicted as destiny.

As his daughter Barbara Sabatino told it, her father was a pharmacist who saw a newspaper advertisement that a location of the Whelan’s Drug Store chain was for sale in Port Washington. She joked that her father must have confused his presidents, ending up on a train to Port Jefferson instead.

It was his lucky day, because a storefront in the same building that currently houses Port Jeff Army Navy also

happened to have a Whelan’s location up for sale. He started his pharmacy at the site, eventually buying the building in 1958 with his brother Samuel. His children, Barbara and Peter, have owned the location since his death in 1977, operating as Port Jeff Army Navy since 1999, though the store underwent several transformations over its 80-year lifespan in the Sabatino family. Later this year, the location will embark on another transition, as Sabatino’s son and daughter plan to retire and close up shop. Barbara Sabatino, a Port Jeff Village resident, joked she and her brother, who lives in Port Jeff Station, are getting old and are ready for some relaxation and travel time.

“I always used to say, ‘We’re Madonna,’” she said. “You know how Madonna always used to reinvent herself? Well we’re just like Madonna, reinventing ourselves.”

Her father’s 1939 mistake had a lasting impact not only on his business, but also his personal life. Sabatino said her parents met when her mother Frances went on a trip to her family’s property in Coram, and before heading home on the train, as fate would have it, stopped for a soda at Whelan’s.

“If he didn’t come to Port Jefferson by accident, and if my grandfather didn’t own property out in Coram, [my parents] never would have met and we never would have been here,” Sabatino said. “This was a happy mistake.”

“You know how Madonna always used to reinvent herself? Well we’re just like Madonna, reinventing ourselves.”

— Barbara Sabatino

The Sabatino children were faced with a decision in 1999, though it was far from the first time, having transformed the pharmacy into a stationary store in prior years, and even adjusting the spelling of the name in decades past. Whelan’s Drug Store had to change to “Weylan’s” in the 1960s when the company decided to

require franchise owners to license the name for $100 a month, according to Sabatino. Her dad decided instead to flip the “h” in the sign over to a “y” and tweaked the order of the letters, allowing them to keep their vibrant neon signage and avoid the fee.

The opening of a couple of office supply stores nearby decimated the business, and Sabatino said she and her brother settled on becoming an Army Navy store because of a hole left in the market — Mac Snyder’s was a long-standing Army Navy store in downtown Port Jeff that closed a few years earlier. At their store, veterans and military aficionados could purchase ribbons and Army-Navy accessories, recover lost medals, buy uniforms and other items like firearms and camping gear.

“It was a natural draw with Peter being in the Navy for 11 years,” Barbara Sabatino said, adding that she used to shop at Mac Snyder’s and always found it a cool place to be. “Out of all of our incarnations, this was my favorite. It’s fun, and the customers are lovely.”

Both Sabatinos noted how special it was to be able to assist active and former military personnel in getting what they needed in the store, which also allowed them to interact with some of the country’s most upstanding and honorable citizens.

“After Barbara suggested the idea of an Army Navy store it brought back a lot of memories, and I said to her, ‘That’s a good idea, that’ll work,’” he said. “There’s a lot of people from Vietnam that are trying to replace all of the stuff they have, and we’re able to get the items in for them.”

At the public village board meeting in June — Barbara Sabatino is a regular fixture at these meetings — a village resident mentioned the pair’s impending retirement, currently slated for the end of August.

“If Barbara is happy, I’m happy,” Village Mayor Margot Garant said upon hearing the news, adding that she

wished her well.

Their impact on the community will be a lasting one. Sabatino said the store owners not only prospered in business during their time uptown, but also gave back to help those around them by helping neighborhood kids with homework, advocating successfully for a new park on Texaco Avenue in recent years and even supplying transportation to village events for uptown kids who wouldn’t have otherwise had a means to get there.

Sabatino shared a card a longtime customer sent to her and her brother when they heard the news.

“At first I was very upset to hear that you were closing because we’re not only losing the best store around, but also the friendliest and most helpful people out there,” the card said. “Port Jeff Army Navy’s goods, services and friendship will absolutely be missed. I am happy that you are retiring. You deserve to rest and be happy and enjoy your family and friends.”

This post was updated June 13.

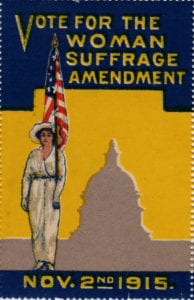

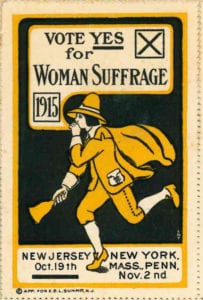

Prohibition Night returns to Stony Brook with suffrage on the mind

By Kyle Barr

If there’s anything that we know about the 1920s, it’s that the parties were wild. Despite, or likely because, of Prohibition, the music was loud and idiosyncratic as jazz came onto the scene, and the alcohol flowed as if by fountains into the expecting mouths of flappers and bootleggers alike.

Setauket’s Three Village Historical Society, in collaboration with The Jazz Loft in Stony Brook is hoping to bring that period of time back to life with the second running of their annual Prohibition Night fundraiser at The Jazz Loft next Thursday, June 14 from 6:30 to 9:30 p.m. The event, sponsored by the Montauk Brewing Company, will include snacks, wine, beer and raffles.

This time the TVHS is adding an extra layer of early 20th-century history with a new emphasis on the women’s suffrage movement and how that tied into a time of cultural revolution.

“You had this revolution with the women’s movement and the right to vote, and you had this revolution with the clothing, with flappers and the Charleston and the bobbed haircuts,” said Tom Manuel, owner of The Jazz Loft. “These were real renegade statements of society and culture, and its cool when you put them together.”

The Jazz Loft will have several items on display relating to women’s suffrage, including several articles, papers and artifacts housed in display cases as well as a mannequin fully dressed up in the class women’s suffrage garb with a large purple sash reading “Votes for Women,” courtesy of Nan Guzzetta of Antique Costumes & Prop Rental by Nan in Port Jefferson.

“[The movement] was really ahead of its time,” said Stephen Healy, president of the Three Village Historical Society. “It’s interesting to see if history is going to repeat itself or we will move on from here. The movement has been a longtime coming.”

That historical revolution collided with the cultural revolution of the 1920s, as many of the same women who campaigned for the women’s vote also stumped for the temperance movement. Suddenly, with the ban of the sale and consumption of alcohol in 1919, a whole new era of organized crime and mass criminality was born as the sale of alcohol eclipsed any decade before or after it.

“Everybody became creative with getting alcohol,” Healy said. “From everything with potato farmers out on the east end of Long Island and vodka creation, and I can’t imagine [the activity] between the water and the farms and the amount of backdoor distributing that was taking place on Long Island.”

But it wouldn’t be the 1920s without jazz, and Manuel said he has that covered. Manuel’s band, The Hot Peppers, will be performing live music straight from the jazz giants of the period such as Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, Thomas “Fats” Waller and more.

“I think for us it really supports and makes a statement about who we are,” Manuel said. “Our mission is jazz preservation, jazz education and jazz performance. Any time we can take history and allow it to come to life, we served our mission.”

Last year’s Prohibition Night was supremely successful with sold out tickets and a packed room. Healy said he expects this year to do just as good or even better.

“It was a great success, it sold out, and it gave us some cross pollination between history and The Jazz Loft,” Healy said.

Manuel agreed that the event is the perfect blend of history and recreation. “Any time we collaborate with something in the community, it really solidifies the statement they say about jazz, which is that it’s all about collaboration,” he said.

The Jazz Loft, located at 275 Christian Ave. in Stony Brook Village, will host the 2nd annual Prohibition Night: Celebrating 100 Years of Women’s Suffrage in New York State on Thursday, June 14 from 6:30 to 9:30 p.m. Tickets are $25 adults, $20 seniors, $15 students. Period costumes are encouraged. To order, call 631-751-1895 or visit www.thejazzloft.org.

Living History tours return to the Vanderbilt Museum

The Suffolk County Vanderbilt Museum in Centerport turns back the clock once again by offering its popular weekend Living History tours now through Sept. 2. For more than a decade, these tours have delighted visitors to the elegant 24-room, Spanish Revival waterfront mansion, Eagle’s Nest, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Vanderbilt has been called a “museum of a museum” — the mansion, natural-history and marine collections galleries are preserved exactly as they were when the Vanderbilts lived on the estate.

Guides dressed as members of the Vanderbilt family and household staff tell stories about the mansion’s famous residents and their world-renowned visitors. Stories told on the tours are based on the oral histories of people who worked for the Vanderbilts as teenagers and young adults. Some stories originated in William K. Vanderbilt II’s books of his world travels and extensive sea journeys.

This summer it will be 1936 again. Consuelo Vanderbilt Balsan is enjoying a reunion of her friends in the women’s suffrage movement.

“The movie ‘Captains Courageous’ with Spencer Tracy is playing in the theaters, and Agatha Christie’s new novel, ‘Dumb Witness,’ is in the bookstores,” said Stephanie Gress, director of curatorial affairs. “Legendary aviator Amelia Earhart is lost at sea in July, and European leaders are faced with threats of German expansion. And the U.S. Post Office issues a commemorative stamp in honor of the women’s voting rights activist and social reformer Susan B. Anthony on the 30th anniversary of her death in 1906.”

Earlier in 1936, New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia — who supported women’s voting rights — had been the keynote speaker at a dinner at the city’s Biltmore Hotel to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the founding of the Women’s City Club in New York. The Living History presentation is set against this background of national and international news.

LaGuardia is invited to Eagle’s Nest to join a few of the Vanderbilt family members — including Vanderbilt’s brother, Harold; his sister, Consuelo, the Duchess of Marlborough; and her guests Elizabeth Arden, Anne Morgan and her nephew, Henry Sturgis Morgan, Gress said. Consuelo and her guests reminisce about their younger days at suffragette rallies.

The museum will display items in two guest rooms that commemorate the centennial of women’s right to vote in New York State. Included will be an enlargement of the Susan B. Anthony stamp, suffrage banners and sashes and an authentic outfit worn in that era by Consuelo. (Vanderbilt’s mother, Alva, also had been active in the movement.)

The Living History cast: Ellen Mason will play Elizabeth Arden, who created the American beauty industry. Yachtsman Harold Vanderbilt — three-time winner of the America’s Cup, and expert on contract bridge — will be portrayed by Jim Ryan and Gerard Crosson. Peter Reganato will be Pietro, the Italian chef. Dale Spencer will perform as William Belanske, the curator and artist who traveled with Vanderbilt on his epic journeys. Anne Morgan will be played by Judy Pfeffer and Beverly Pokorny.

The Suffolk County Vanderbilt Museum, 180 Little Neck Road, Centerport will present its Living History tours in the mansion on Saturdays and Sundays at 12, 1, 2, 3 and 4 p.m. Tickets: $8 per person, available only at the door, are in addition to the museum’s general admission fee of $8 adults, $7 senior and students, $5 children ages 12 and under. Children ages 2 and under are free. For more information, please call 631-854-5579 or visit www.vanderbiltmuseum.org.

Exploring family tree plays a part in local history

By Beverly C. Tyler

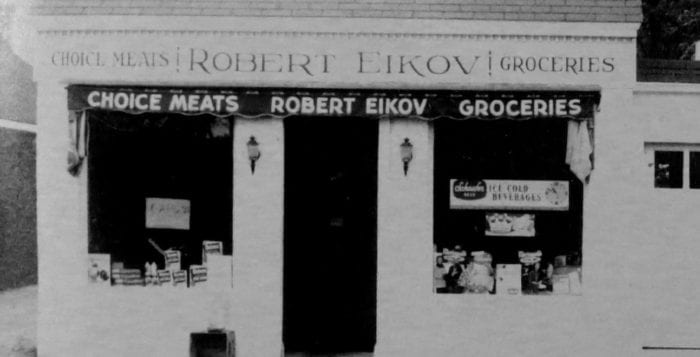

In an oral history interview with Joseph Eikov, who was born in Setauket in 1903, he talked about life in East Setauket in the early 20th century. His father came here from Warsaw, Poland.

“They all migrated here,” he said. “My mother [Dora Pinnes] from [Kopyl] Russia … All the Jews migrated here … They were called greenhorns. They came here with badges on. They came here to work in the [East Setauket] rubber factory and after the factory burned down [1905], then they started to leave. That’s when Pinnes [Dora Pinnes’ brother Herman, who opened a kosher butcher shop in East Setauket] went from kosher. They moved away gradually until there were very few left.”

Local history is a combination of the history of people, places and events. All of these elements are needed to understand and enjoy the history of a community or family history. Research into one of these areas naturally spills over into the others. Sources of information are so varied that they cannot be listed or explained in one short article; however, getting started in the exploration of local history is as simple as finding out about your own family’s history.

Without the research provided by family historians, the collections of local history in libraries and historical societies would be much less useful. If your family comes from Long Island, plan a visit to the Suffolk County Historical Society library in Riverhead at 300 W. Main St. The society maintains one of the largest files of genealogical material in Suffolk County. Its Weathervane Gift Shop also has a large collection of books, pamphlets and other materials on Long Island history and genealogy. The Long Island collection in the Emma S. Clark Memorial Library, 120 Main St. in East Setauket, includes a large number of published genealogies. These include both individual and family histories. The manuscript collection of the Three Village Historical Society (the Capt. Edward R. Rhodes Memorial Collection of Local History) in the Emma Clark Library includes a number of typed and handwritten genealogies. Most of these are family histories, but some include extensive information on specific individuals as well.

It is important for more local residents to provide information on their families to be placed in the Three Village local history collection. In this way the history of Setauket and Stony Brook can be kept up-to-date.

The information compiled by family members includes not only the names, dates and relationships of prior generations, but often supplies the interesting stories about their lives that makes local history so interesting. But where to start? Most genealogists recommend that those entering the field for the first time read a good basic book on the subject of genealogy and family history. Researching family history can be an enjoyable undertaking if you dig into the past with the right tools at your disposal.

Family history has, with the advent of the internet, become a popular pastime. There are a number of sites that can help with family research. Start with www.live-brary.com. Click on Local History and Genealogy and then on Topic Guide Genealogy. The Mormons have a free site you can use at www.genealogy.com. Ancestry is a for-profit site at www.ancestry.com that can be accessed for free at the Emma Clark and other local libraries. Heritage Quest, on the other hand, can be accessed from the library or at home by signing in to the library website at www.emmaclark.org. One of many interesting sites for genealogy and family history is www.stevemorse.org.

Books on genealogy and family history are available at libraries. At the Emma Clark library, upstairs under 929.1, are books such as: “The Troubleshooter’s Guide to Do-It-Yourself Genealogy” by W. Daniel Quillen (both 2016 and 2014 editions), “How to Do Everything Genealogy” by George Morgan (2015) and “Genealogy Online for Dummies” by Matthew and April Helm (2014). There are also a number of DVDs on genealogy and family history.

To begin your family history, just remember to start with yourself. You are the beginning of the search. Record all the known facts about yourself — birth, baptism and marriage dates — and all of your known brothers, sisters, uncles, aunts, parents and grandparents. Next, use home sources. Find out what kind of genealogical materials you have in your home and relatives’ homes including family bibles, newspaper clippings, military certificates, birth and death certificates, marriage licenses, diaries, letters, scrapbooks, backs of pictures and family histories. Don’t forget to talk to or write to — email if possible — your relatives, even the ones you haven’t spoken to in years. Family gatherings can also provide a good source of information about family history and folklore.

However you get started, get going. You will find the journey well worth the effort.

Beverly C. Tyler is Three Village Historical Society historian and author of books available from the society at 93 North Country Road, Setauket. For more information, call 631-751-3730 or visit www.tvhs.org.

Tesla lab in Shoreham looking to make historic site list

By Kyle Barr

Shoreham’s Wardenclyffe property, the site of famed Serbian-American inventor Nikola Tesla’s last living laboratory, is up for consideration for historical site status by the New York State Historic Preservation Office June 7.

“We want to make the world aware, more than it is now, of the site’s importance,” said Jane Alcorn, president of the board of directors of Tesla Science Center at Wardenclyffe. “It gives the community and our investors some assurance that we’re moving in the right direction, that were not just gaining local recognition, but state and national as well.”

In 2012 the science center worked with The Oatmeal comic website to launch a successful Indiegogo campaign that raised $1.37 million to purchase the land. Since then the nonprofit has renovated the property with plans to turn the site into a museum and incubator for technology-based business startups.

Alcorn said the board hired a historic architect consultant who documented the land and its legacy. The group worked for months crafting a 92-page document describing Tesla’s life along with the many minute details of the 16-acre property, such as which buildings are historic and which are not, when each was built, and by what person and company.

Marc Alessi, the science center’s executive director, said that having the property on the historic register would help to indefinitely safeguard the land.

“It’s preserving it for future generations,” Alessi said. “When you get something registered as a historic landmark, we’ll be able to rest easy knowing 500 years from now if society completely changes, there is a very good chance the lab will still be there.”

“When you get something registered as a historic landmark, we’ll be able to rest easy knowing 500 years from now if society completely changes, there is a very good chance the lab will still be there.”

— Marc Alessi

Alcorn said getting historical status would not only increase the project’s notoriety, but would also allow the group to apply for state grants they wouldn’t be eligible for without the historic status.

“It’s often one of the requirements of many state grants — that you are located on the historic register,” Alcorn said. “We’ve been eliminated from granting opportunities in the past due to that lack.”

Many modern-day entrepreneurs and scientists have a vested interest in the lab’s history. Tesla, a self-starter and entrepreneur, created many technological innovations still used today, such as alternating current and electromagnetism technology. His research influenced modern day X-rays.

In the early 1900s Tesla acquired the Wardenclyffe property in Shoreham to test his theories of being able to wirelessly transmit electrical messages. The property housed a huge 187-foot tower for the purpose, but in 1903 creditors confiscated his equipment, and in 1917 the tower was demolished. The concrete feet used to hold the structure can still be seen on the property today.

The science center submitted the final historic register application nearly a month ago, and next week it will be reviewed by the state’s national register review board. The review process takes several weeks, and if

accepted, the property will be put on the state register of historic places. The application will then automatically go to the National Register of Historic Places review board for the potential of being put on the national registry. That process will take several months.

“Not everything submitted to the national registry gets listed, but New York has a very good track record, so hopefully we’ll be hearing a good thing from this one,” said Jennifer Betsworth, a historic preservation

specialist for the state preservation department.

Only a day after the center announced its application, it had more than 6,700 people sign letters in support of the application, according to Alessi, and were sent to the state historic preservation review board.

Betsworth said despite how the property has been modified through the years, it has value as Tesla’s last intact laboratory and has historical significance as the site of some of his last and most ambitious inventions.

“It’s a bit complicated because it’s a building that’s absolutely covered with later additions that aren’t historic, so its value is not necessarily immediately obvious,” said Betsworth. “If this wasn’t the last remaining laboratory related to Tesla, it might not have been eligible. The incredible rarity and significance of this

resource is what it has going for it.”

The science center is currently working to fundraise for the first phase of a project that would turn two buildings on the grounds into exhibition spaces for science education. The fundraising has reached $6 million out of the planned $20 million, according to Alessi. The science center hopes to have the first part of a functioning museum up and running by the end of next year.