Reviewed by Jeffrey Sanzel

Talia Carner’s The Third Daughter (William-Morrow and Company) is one of the most intriguing and riveting books published in the last year. Batya is the third of poor Russian milkman Koppel’s four daughters. The Third Daughter begins in 1889 as the family flee their ravaged shtetel of Komarinoe. If this seems a nod towards Sholom Aleichim’s Tevye, it is not unintentional. In essence, Carner is using the end of those stories as a place to begin her narrative but in no way does it attempt to be a sequel. The Third Daughter is wholly original. In the prologue, with a few simple strokes of place and time, she is able to evoke the horror of the pogrom. This sets the tone and style for the rest of Batya’s grim journey. It is told vividly but with never a wasted word or thought.

The family’s goal is to travel to America. “God wasn’t here [in Europe], where His Jews were being tortured and exiled, if not murdered. Maybe he was in the Holy Land — but more likely He was in America, where everyone prospered and ate chicken every day.” Koppel’s brother — with whom he has had no contact for many years — lives in Pittsburgh; this becomes the golden dream.

With no money or way to travel to the United States, they are forced to live in conditions worse than they endured in Komarinoe. There is a shabbat meal with a cobbler’s family that distills the grueling and grinding poverty of eastern Europe. Unlike many portrayals of these small villages, Carner never glamourizes. This is a hallmark of the entire book.

Enter Yitizk Moskowitz, a prosperous businessman, who takes a shine to the fourteen year-old Batya. He makes a deal with Koppel for Batya’s hand in marriage. Initially, he agrees that he will come back for Batya in two years but then changes his mind, saying that he will take her now, and she will live with his sister until she is sixteen and of age. Koppel readily agrees.

This begins the dark heart of the book. Moskowitz is not the businessman he claims but, instead, a procurer. (Another nod towards Aleichem, this time his short story The Man from Buenos Aires.) Later, Moskowitz describes himself: “‘My hands never get dirty in menial work,’ he liked to say when he delegated the beatings and cigarette burnings to others.” He assaults Batya; her violation in essence brands her. “‘You are mine now,’ said Reb Moskowitz. ‘Forever.’” He then turns her over to a thug who transports her to a ship where she is further abused. Finally, she lands in Buenos Aires.

This begins the dark heart of the book. Moskowitz is not the businessman he claims but, instead, a procurer. (Another nod towards Aleichem, this time his short story The Man from Buenos Aires.) Later, Moskowitz describes himself: “‘My hands never get dirty in menial work,’ he liked to say when he delegated the beatings and cigarette burnings to others.” He assaults Batya; her violation in essence brands her. “‘You are mine now,’ said Reb Moskowitz. ‘Forever.’” He then turns her over to a thug who transports her to a ship where she is further abused. Finally, she lands in Buenos Aires.

Batya enters a realm of torture and debasement, a world devoid of humanity: the legal brothels of this Argentinian city. There, she is sent to Freda, Moskowitz’s equally pitiless sister, who runs the house for him.

Carner has done her research and her depiction of Zwi Migdal, the far-reaching union of pimps, is as ugly as it is accurate. This ruthless organization rules through physical violence, bribes, and corruption. Buenos Aires is shown as a community that is just as poor as the one Batya escaped with the difference that this South American hell is a glimpse of Sodom and Gomorrah.

The anti-Semitism of the Old Country is replaced by an equally appalling existence in the New World. Carner’s ability to make the reader feel Batya’s shame and fear is extraordinary; even among her own people, Batya is an outcast, as shown by a scene in which her humiliation is furthered as she is driven from the synagogue. Carner never lets us forget that Bayta is a child, an innocent thrust into a nightmare. There is one heart-rending moment where the girl creates a doll out of a pillowcase, attempting to give herself a moment of solace. Batya, whose name means “daughter of God,” is paradoxically given the name Esperanza, which translates as “hope.”

There are occasional odd acts of kindness. Freda allows Batya to sit shiva (the ritual seven day period of mourning) for her mother. The prostitutes form a quick female minion, the group of ten that is the sole province of men, to pray with her in her loss. The laying to rest of a prostitute who has committed slow suicide shows a kindness underneath the day-to-day suffering. Another time, Batya is taken to a café where she encounters girls from another house: “She caught the eyes of a sister across the table and smiled. She didn’t know the woman’s name, and they couldn’t chat over the men’s conversation, but the bond of shared tragic history was a fine spiderweb that tied them together.”

Carner never allows sentimentality to overtake the reality. Batya’s wondrous visit to an opera house is rightly juxtaposed with the hideous persecution of an abducted girl who refused to become a prostitute. Her subsequent descent into insanity and the knowledge of her eventual fate cuts through any joy.

Batya is introduced to the tango, which becomes both thematic and pivotal to what ensues. She is given context by Nettie, another prostitute: “This is what happens to sadness once it reaches Argentina. We can either cry about the past or laugh about the future. So we drown out the old pain in dance.” This is particularly germane to the final quarter of the book which involves Batya’s attempts to both bring her family over and to free herself from her bondage. It is as page-turning and tense as any thriller, with many complications that build the relentless suspense. Batya is forced to make life-altering choices, each with possibly calamitous repercussions.

Talia Carner’s The Third Daughter is an epic work that is rooted in a deep sense of truth. While it deals with a cruel and terrifying chapter of history, the novel is also a celebration of the ability of great writing to transport and enlighten. It is a work of art, of craft, but, above all, humanity.

The Third Daughter is available at bookrevue.com, barnesandnoble.com and amazon.com.

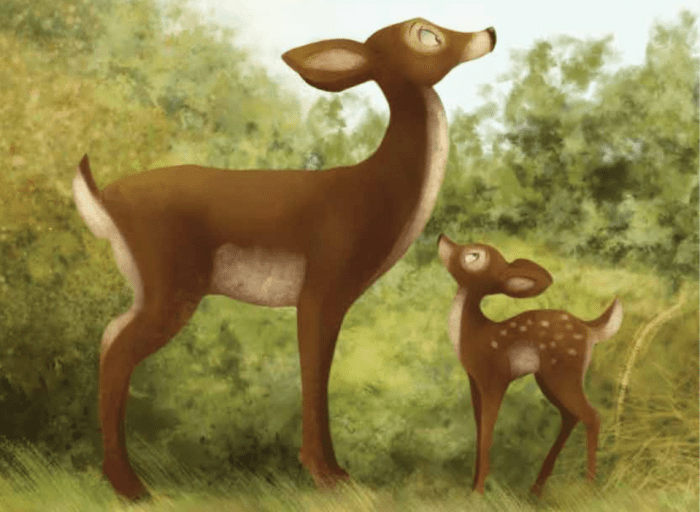

Safina divides the book into the study of sperm whales (families); scarlet macaws (beauty); and chimpanzees (peace). Each of the three sections is rich, detailed and engaging enough to be a book onto itself. He has brought them together under the umbrella of his exploration of culture.

Safina divides the book into the study of sperm whales (families); scarlet macaws (beauty); and chimpanzees (peace). Each of the three sections is rich, detailed and engaging enough to be a book onto itself. He has brought them together under the umbrella of his exploration of culture.

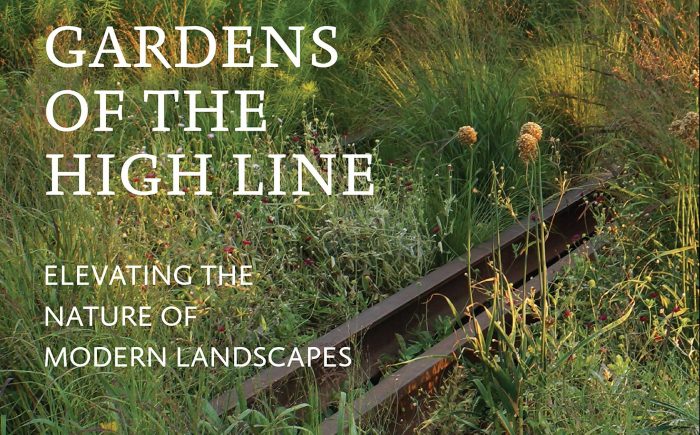

“Though it’s unlikely there will ever be another place quite like the High Line, it offers a wealth of insights and approaches worthy of emulation in gardens large or small, public or private. Authentic in spirit and execution, the High Line’s gardens offer a journey that is intriguing, unpredictable, imperfect, and, above all, transformative.”

“Though it’s unlikely there will ever be another place quite like the High Line, it offers a wealth of insights and approaches worthy of emulation in gardens large or small, public or private. Authentic in spirit and execution, the High Line’s gardens offer a journey that is intriguing, unpredictable, imperfect, and, above all, transformative.”

The Hawkins-Mount Homestead, in Stony Brook, was used several times in 1802 as a meeting place for the Suffolk Lodge; its owner, Major Jonas Hawkins, was a member of the Culper Spy Ring during the American Revolution. Chief Crazy Bull, grandson to the famous Sioux Chief Sitting Bull of the Hunkpapa Lakota Tripe, was a member of the Suffolk No. 60 Lodge, which is still located on Main Street in Port Jefferson.

The Hawkins-Mount Homestead, in Stony Brook, was used several times in 1802 as a meeting place for the Suffolk Lodge; its owner, Major Jonas Hawkins, was a member of the Culper Spy Ring during the American Revolution. Chief Crazy Bull, grandson to the famous Sioux Chief Sitting Bull of the Hunkpapa Lakota Tripe, was a member of the Suffolk No. 60 Lodge, which is still located on Main Street in Port Jefferson.

According to their sources, much of the testing on animals is of limited-to-no value given the dissimilarities of humans and animals. In addition, computer simulations are slowly replacing many areas of exploration: “In the future, the math may replace the mouse.” Finally, they encourage people to only use products and brands that are proven to be cruelty-free.

According to their sources, much of the testing on animals is of limited-to-no value given the dissimilarities of humans and animals. In addition, computer simulations are slowly replacing many areas of exploration: “In the future, the math may replace the mouse.” Finally, they encourage people to only use products and brands that are proven to be cruelty-free.

Why did you decide to write this book?

Why did you decide to write this book? What about the illustrations? Did you do them, or did you work with someone else?

What about the illustrations? Did you do them, or did you work with someone else?