By John L. Turner

This is the first in a two-part series on Long Island’s water supply.

When thinking about Long Island’s groundwater supply — its drinking water aquifers — it is helpful to visualize a food you might eat while drinking water — say, a three-tiered, open-faced turkey sandwich — a slice of cheese on top, a juicy, thick tomato disk in the middle, a slice of turkey on the bottom, all resting on a piece of hard, crusty bread.

Well, substitute the Upper Glacial Aquifer for the cheese, the thicker Magothy Aquifer for the tomato, the Lloyd Aquifer for the turkey, and a “basement of bedrock” for the bread and you’ve got Long Island’s tiered groundwater system. It is this collection of groundwater aquifers — these sections of the sandwich — that are the sole source of water for all the uses Long Islanders use water for. Hydrologists estimate there’s about 90 trillion gallons of water contained in Long Island’s groundwater supply.

Our sandwich model described above is not fully accurate in that there is another layer called the Raritan Clay formation separating the Magothy and Lloyd Aquifers. This clay layer, about 200 feet thick, retards water movement (for a number of reasons water moves painfully slow through clay) and is referred to as an aquitard. So, in our sandwich model let’s make the thin but impactive clay formation a layer of mustard or mayonnaise. With the exception of this clay-confining layer, Long Island is essentially a million-acre sandpile whose geology is generally distinguished by subtle changes in the composition, texture, and porosity of its geological materials — varying mixtures of silt, clay, sand, gravel and cobbles which affects rates of water transmissivity or movement.

The basement of bedrock (the bread in our sandwich) that underlies all of Long Island is metamorphic rock estimated to be about 400 million years old. It slants from the northwest to the southeast dipping at about 50 feet to the mile. So, while the thickness of the freshwater aquifers in northwest Queens is only a few hundred feet, it is approximately 2,000 feet thick in western Southampton.

On the North and South Forks and the south shore barrier islands, freshwater doesn’t extend all the way to bedrock as it does in Nassau County and much of western and central Suffolk County. It is shallowest on the barrier islands, the freshwater lens extending down only several dozen feet.

On the North Fork it goes a little deeper before the water becomes salty and it is deepest on the wide South Fork where the freshwater lens extends downward about 550-600 feet. The depth of the aquifer is influenced by how many feet above sea level the water table is. There’s a hydrological formula, called the Ghyben-Herzberg principle, that states for every foot of water above sea level there’s 40 feet of freshwater beneath.

The water in the groundwater aquifers isn’t stored in large subterranean pools or caverns, as it is in some other places in the country with markedly different geology, Rather, the water is situated between the tiny, interstitial spaces existing between the countless sand particles that collectively make up Long Island. Given this, it is not surprising that groundwater flows (under the influence of gravity) slowly downward and sideways (depending where in the aquifer the water is located) moving on the order of just a few feet a day at most but typically in the ballpark of about one foot per day.

It takes dozens to hundreds to thousands of years for water to move through the system, all depending where it first landed on the island’s surface. Water pumped from the seaward edge of the lowest aquifer — the Lloyd Aquifer — may have fallen as rain many years before the beginning of the ancient Greek Empire.

In the late 1970’s several governmental studies helped us to better understand some of the basics as to how the groundwater system works. One of the important takeaways from this research was that it is the middle half to two-thirds of the island that is most important for recharge — this segment is known as the “deep-flow recharge area” because a raindrop that lands here will move vertically downward recharging the vast groundwater supply.

The middle of this area is knows as the “groundwater divide”; a water drop that lands to the south of the divide will move downward and then laterally in a southern direction discharging into one of the south shore bays or the salty groundwater underneath the Atlantic Ocean while a drop to the north will move eventually into Long Island Sound or the sandy sediments beneath it.

Hydrologists have determined that for every square mile of land (640 acres) an average of about two million gallons of rain water lands on the surface with about one million gallons recharging the groundwater supply on a daily basis. What happens to the other one million gallons? It evaporates, runs off into streams and other wetlands, or is taken up by trees and other plants that need it to sustain life processes such as transpiration (a large oak tree needs about 110 gallons of water daily to survive).

In contrast, raindrops that land in locations nearer to the coasts such as in Setauket, northern Smithtown, southern Brookhaven, Babylon, or other places along the north and south shores don’t become part of the vast groundwater reservoir; instead, after percolating into the ground the water moves horizontally, discharging either into a stream that flows to salty water or into the salty groundwater that surrounds Long Island. These landscape segments are referred to as “shallow-flow recharge areas.”

The higher elevations along the Ronkonkoma Moraine (the central spine of Long Island created by glacial action about 40,000 years ago) are also the highest points in the water table although the water table elevation contours are a dampened expression of the land surface. So, in the West Hills region of Huntington where Jayne’s Hill is located, the highest point on Long Island topping out at a little more than 400 feet, the elevation of the water table is about 80 feet above sea level.

Below the water table is the saturated zone and above it the unsaturated zone where air, instead of water, exists in the tiny spaces between the sand particles (in the Jayne’s Hill case the unsaturated zone runs about 320 feet). It is the water (more precisely its weight) in the higher regions of the saturated zones that pushes on the water beneath it, driving water in the lower portions to move at first sideways or laterally and then to upwell into the salty groundwater under the ocean. Due to the weight of the water the freshwater-saltwater interface is actually offshore on both coasts, meaning you could drill from a platform a mile off Jones Beach and tap into freshwater if you were to drill several hundred feet down.

A wetland forms where the land surface and water table intersect. It may be Lake Ronkonkoma, the Nissequogue or Peconic River, or any of the more than one hundred streams that drain the aquifer discharging into bays and harbors around Long Island. So when you’re gazing at the surface of Lake Ronkonkoma you’re looking at the water table — the top of the Long Island groundwater system. Since the water table elevations can change due to varying amounts of rain and snow and pumping by water suppliers these wetlands can be affected; in wet years they may enlarge and discharge more water while in droughts wetlands can largely dry up which happened on Long Island in the 1960’s.

It is clear, given the isolated nature of our water supply — our freshwater bubble surrounded by hostile salt water — that we are captains of our own fate. Our groundwater supply is the only source of water to meet all of our collective needs and wants. There are no magical underground freshwater connections to Connecticut, mainland New York, or New Jersey. We are not tied into, nor is it likely we will ever be able to tap into, New York City’s water supply, provided by the Delaware River and several upstate reservoirs. As the federal Environmental Protection Agency has declared — Long Island is a “sole source aquifer.” To paraphrase the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moyhihan: “Long Islanders all drink from the same well.” Indeed we do.

The next article will detail the quality and quantity problems facing our groundwater supply.

A resident of Setauket, John Turner is conservation chair of the Four Harbors Audubon Society, author of “Exploring the Other Island: A Seasonal Nature Guide to Long Island” and president of Alula Birding & Natural History Tours.

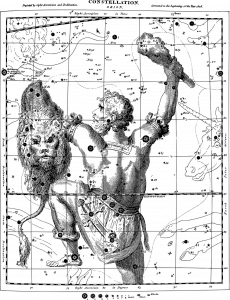

When I last looked at the Milky Way, a couple of days ago, it reminded me of our most humble place in the universal ethos and of a famous line by the poet Robinson Jeffers: “There is nothing like astronomy to pull the stuff out of man, His stupid dreams and red-rooster importance: let him count the star-swirls”.

When I last looked at the Milky Way, a couple of days ago, it reminded me of our most humble place in the universal ethos and of a famous line by the poet Robinson Jeffers: “There is nothing like astronomy to pull the stuff out of man, His stupid dreams and red-rooster importance: let him count the star-swirls”.

For example, two scientists discussing otter biology need to know what otter species they’re talking about. Is it the Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris)? Or maybe the River Otter (Lontra canadensis) or Asian Small-clawed Otter (Aonyx cinereus)? How about Giant River Otter, (Pteronura brasiliensis), European Otter (Lutra lutra) or any other of the thirteen species of otters found in the world. In discussing some aspect of otter ecology or biology, just mentioning “otter” may not be sufficient to provide the level of specificity or accuracy needed. Researchers need to know they’re both talking about the same species of otter. Or bacteria. Or slime mold. Or many other species that can affect us.

For example, two scientists discussing otter biology need to know what otter species they’re talking about. Is it the Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris)? Or maybe the River Otter (Lontra canadensis) or Asian Small-clawed Otter (Aonyx cinereus)? How about Giant River Otter, (Pteronura brasiliensis), European Otter (Lutra lutra) or any other of the thirteen species of otters found in the world. In discussing some aspect of otter ecology or biology, just mentioning “otter” may not be sufficient to provide the level of specificity or accuracy needed. Researchers need to know they’re both talking about the same species of otter. Or bacteria. Or slime mold. Or many other species that can affect us.