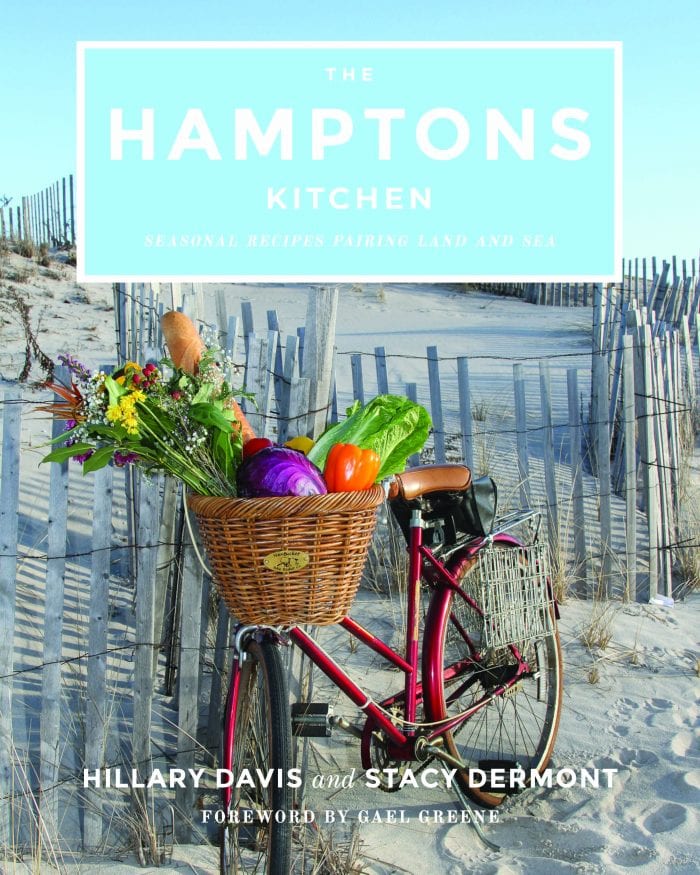

‘This book is a love affair with seaside eating.’

— from the Foreword by Gael Greene

Reviewed by Jeffrey Sanzel

Hillary Davis and Stacy Dermont have collaborated on a book that is more than just a collection of recipes. It is an engagingly written celebration of not just seasonal cooking but local sourcing. They have brought together multiple elements of Long Island and channeled them into a guide that is both entertaining and practical. The love for their home is furthered in its citing of neighborhood farms and businesses and the plethora of ingredients that they provide to make magic in the kitchen.

“Over many meals and food-oriented adventures,” writes Davis, “we came to the conclusion that we wanted to share what we love about this very special part of the world. … In the way we have chosen to live, we shop at our local farm stands and farmers’ markets for most or all of our fresh produce, as much to revel in the amazing quality and choice as to feel as if we are taking part in preserving our small-farm heritage.”

This local-centric ideology is a passion for both writer-chefs and this clearly honest zeal continues throughout the book. Prior to each recipe there is a succinct and informative narrative piece: a personal anecdote or a slice of hyperlocal detail. Both authors pen in a homey narrative, as if they are sharing a bit of themselves as they prepare the plethora of repasts. Whether it’s a history of the ingredients or a “one time when” they enrich the entire reading experience.

In the first part of the book, there is a discussion about the importance of pairings of food to beverages. Their thesis is that they should amplify or contrast to enhance the meal. Davis and Dermont explain each and propose a local drink as complement. Most often, there is a recommendation of a product from one of the 60 local wineries, 40 craft breweries, or one of the many distilleries or cideries. Sometimes, they simply advise an herbal tea. These details are a wonderful augmentation.

The book proper is divided by seasons: spring, low summer, high summer, fall and winter. Presented is a very detailed list of what is in season and when, a list that should be kept nearby throughout the year. There is even a plea for “Nothing Goes to Waste” with ideas for using remnants in making stock or composting.

Each section of the book contains small plates, salads, main courses and desserts. In the hundred recipes, there is a nice mix of well-loved and new dishes as well as unique takes on popular favorites.

It is a tribute to the clarity of the writing that even the more complicated and challenging recipes are explained in such a way that novice cooks can accomplish them. They are given step by step with just the right amount of detail. There are also instructions on topics ranging from the roasting of garlic to the blanching of fresh bamboo shoots to the selection and cooking of clams. This is a wealth of knowledge, expertly shared.

It would be impossible to highlight all of the wonderful choices that are on offer: Potato Cheesecake with Caramel Crust, Kale Poppers, Blue Cheese Chicken with Strawberry Salsa, Long Island Duck Breasts with Duck Walk Vineyards Blueberry Port Sauce, BLT Macaroni Salad with Ham Crisps, So Many Tomatoes Sauce over Spaghetti Squash, Peconic Bay Scallops with Riesling Cream, Roasted Montauk Pearl Oysters, Wine Country Beef Stew, Cider-Poached Apples on a Cloud of Cider-Sweetened Ricotta … there is not just something for everyone — there is a bounty of culinary joys.

Special note should be made of the original photography by Barbara Lassen. Lassen’s keen eye brings the dishes to life in dazzling and vivid colors, further reminding us that there is a special multifaceted aesthetic involved in this entire process.

Davis and Dermont’s The Hamptons Kitchen: Seasonal Recipes Pairing Land and Sea will make a wonderful addition to culinary libraries throughout the Island. But even more importantly, it will find its best home in kitchens for many years to come.

The cookbook is available online at Barnes & Noble and Amazon and will be in bookstores by April 7. For upcoming book signings, please visit www.thehamptonskitchen.com.

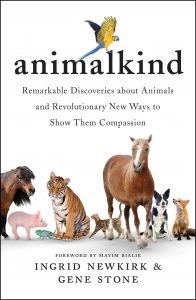

According to their sources, much of the testing on animals is of limited-to-no value given the dissimilarities of humans and animals. In addition, computer simulations are slowly replacing many areas of exploration: “In the future, the math may replace the mouse.” Finally, they encourage people to only use products and brands that are proven to be cruelty-free.

According to their sources, much of the testing on animals is of limited-to-no value given the dissimilarities of humans and animals. In addition, computer simulations are slowly replacing many areas of exploration: “In the future, the math may replace the mouse.” Finally, they encourage people to only use products and brands that are proven to be cruelty-free.

The story begins as the book’s did. Buck, a St. Bernard/Scotch collie, lives in Santa Clara, California, with his master, Judge Miller (a nice cameo by Bradley Whitford). After being stolen and shipped north, he is sold into the service of a mail-delivering dogsled team.

The story begins as the book’s did. Buck, a St. Bernard/Scotch collie, lives in Santa Clara, California, with his master, Judge Miller (a nice cameo by Bradley Whitford). After being stolen and shipped north, he is sold into the service of a mail-delivering dogsled team.

The son (affable Choi Woo Shik) is given the opportunity to tutor an affluent high school student (innocent Jung Ji-so). His sister (wily Park So-dam) forges his degree. When he enters the Park home, his wide-eyed awe is palpable. The house was constructed by a renowned architect and is more museum than home. Bright, modern and spacious, it whispers untold wealth — a stark contrast with the infested living conditions faced by the Kims.

The son (affable Choi Woo Shik) is given the opportunity to tutor an affluent high school student (innocent Jung Ji-so). His sister (wily Park So-dam) forges his degree. When he enters the Park home, his wide-eyed awe is palpable. The house was constructed by a renowned architect and is more museum than home. Bright, modern and spacious, it whispers untold wealth — a stark contrast with the infested living conditions faced by the Kims. From here, the action twists and turns, rises and sinks (like the films labyrinth of staircases) as the Kim family makes themselves indispensable. However, one of the film’s tenures is that making plans is a dangerous thing. What ensues is a host of situations involving a secret bunker, Morse code, a garden party from hell, a rainstorm that becomes a vile deluge and a range of other complications that are both darkly comic and horrifying. From fanciful swindle to shocking violence, the wake of destruction is both surprising and inevitable.

From here, the action twists and turns, rises and sinks (like the films labyrinth of staircases) as the Kim family makes themselves indispensable. However, one of the film’s tenures is that making plans is a dangerous thing. What ensues is a host of situations involving a secret bunker, Morse code, a garden party from hell, a rainstorm that becomes a vile deluge and a range of other complications that are both darkly comic and horrifying. From fanciful swindle to shocking violence, the wake of destruction is both surprising and inevitable. The film is flawlessly directed by Bong Jon-ho, with a constantly shifting pace that never loses its relentless tension. The screenplay (by Jon-ho, along with Han Jin-won) is articulate, smart and outrageously wicked; Hong Kyung-pyo’s desaturated cinematography is the perfect compliment.

The film is flawlessly directed by Bong Jon-ho, with a constantly shifting pace that never loses its relentless tension. The screenplay (by Jon-ho, along with Han Jin-won) is articulate, smart and outrageously wicked; Hong Kyung-pyo’s desaturated cinematography is the perfect compliment.