By Jeffrey Sanzel

In these dark and often challenging times, it is nice to know there are movies and television shows that can take us out of ourselves for an hour or two. It is a welcome opportunity to jump into a rom-com world that is delightful and whimsical and wholly engaging. Netflix’s offering, Love Wedding Repeat, is not that.

With beautiful scenery, a glorious sunshine filled-day, and elegance in everything from the lavish dress to the flawless table settings, it takes a great deal of effort to be this consistently abrasive and charmless. There is a difference between trying very hard and just being very trying. Four Weddings and a Funeral it’s not. Well, maybe just the funeral.

Dean Craig has directed his own screenplay based on the 2012 French film Plan de Table. In the prologue, British Jack (Sam Claflin) attempts to kiss American Dina (Olivia Munn), the roommate of his sister Haley (Eleanor Tomlinson). They are interrupted by a boorish friend of Jack’s and there goes the kiss. Jump three years forward to Hayley’s Roman wedding to Roberto (Tiziano Caputo). Once again, Jack has the opportunity to connect with journalist Dina. The film spends the next hour and a half keeping them apart.

The thin conceit hangs on two things: the name cards at the English table and a misappropriated sedative. The film’s gimmick is that it plays out one scenario with a brutally unhappy ending (truly ugly) and a second with a cheerier resolution. Separating the two is an interlude in fast-forward during which half a dozen possibilities are played out around the table.

The film’s structure is not the film’s problem. Instead, it is as if someone emptied the cliché bag of every wedding movie. “Nothing could spoil this day …” followed by the arrival of the coked-up ex-boyfriend (scenery chewing Jack Farthing). Who could see that coming?

There is the old man who insists on kissing everyone on the mouth. A not Scottish guy in a kilt (Tim Key) — oh, those hilarious kilt jokes — whose inability to talk to women is the source of so much amusement. Of course, given the nature of the film, in the second part, he learns that it all comes down to “just listening.”

A pretentious film director (Paolo Mazzarelli), caricatured right down to the pony tail, is being stalked by the maid of honor, Bryan (Joel Fry). To add further chaos, Bryan has only just learned that he has to give a speech. Don’t forget the obnoxious friend (Aisling Bea) who says everything she thinks but, deep down, just wants to be loved. Don’t worry: She ends up with someone who sees her for who she is, deep down. Freida Pinto is saddled with the thankless role of Jack’s ex, a gorgeous harridan who is tormenting her current boyfriend (Allan Mustafa, who must play a rather unsavory obsession).

There are some truly gross moments that are somehow meant to be funny. There is both the expected and extraneous sex jokes. What’s less than single entendre? The whose-taken-the-sedative-and-is-falling-asleep gag seems interminable and inescapable. These “hijinks” are played out against a great deal of talk about “grabbing choices” and “finding love.” Pick a lane, please.

In theory, it is a clever idea to show two different views of the same day and the matrimonial setting is an ideal choice. But the contrast between the two parts is not strong enough nor are the characters likable enough to root for.

Claflin has a certain warmth but the material doesn’t give him enough variety or backbone. Munn is smart as the object of his affection but seems to be suffering much of the time. Tomlinson, a true English Rose, is handed an unforgivable transgression given the context. Key tries his best to make the supportive friend less of a trope and more of a human being. It comes down to the fact that this is a talented cast who are not served by the writing’s grinding machinations and the often less-than-pleasant characters.

The moral of Love Wedding Repeat is it all depends on where you sit. I guess that’s true. I wish I hadn’t sat in front of the television.

Rated TV-MA for mature audiences only, Love Wedding Repeat is now streaming on Netflix.

The Hawkins-Mount Homestead, in Stony Brook, was used several times in 1802 as a meeting place for the Suffolk Lodge; its owner, Major Jonas Hawkins, was a member of the Culper Spy Ring during the American Revolution. Chief Crazy Bull, grandson to the famous Sioux Chief Sitting Bull of the Hunkpapa Lakota Tripe, was a member of the Suffolk No. 60 Lodge, which is still located on Main Street in Port Jefferson.

The Hawkins-Mount Homestead, in Stony Brook, was used several times in 1802 as a meeting place for the Suffolk Lodge; its owner, Major Jonas Hawkins, was a member of the Culper Spy Ring during the American Revolution. Chief Crazy Bull, grandson to the famous Sioux Chief Sitting Bull of the Hunkpapa Lakota Tripe, was a member of the Suffolk No. 60 Lodge, which is still located on Main Street in Port Jefferson.

Mark Walhberg plays Boston police officer Spenser who is now being released from five years in prison for assaulting his captain (a stock villain played by Michael Gaston). While at first it seems that Spenser’s sole motivation was breaking up a domestic dispute, it is gradually revealed that there is more to it than just the captain’s mistreatment of his wife.

Mark Walhberg plays Boston police officer Spenser who is now being released from five years in prison for assaulting his captain (a stock villain played by Michael Gaston). While at first it seems that Spenser’s sole motivation was breaking up a domestic dispute, it is gradually revealed that there is more to it than just the captain’s mistreatment of his wife.  The tone strips its gears as it shifts between sitcom and deadly serious. A vicious dog attack is played as slapstick in this bizarre mix of real and cartoon violence. Perhaps there was an attempt to make this a common man as super hero vehicle — there are various references to Spenser as Batman — but there is no follow-through on that concept either. The jokey moments come across as precious, with glib quips often followed by an exceptionally ugly moment. It is not impossible to pull off this seemingly incongruent blend; the Dirty Harry movies did it brilliantly. Spenser Confidential doesn’t even try. It just lopes along, leaving a trail (and trial) of clichés.

The tone strips its gears as it shifts between sitcom and deadly serious. A vicious dog attack is played as slapstick in this bizarre mix of real and cartoon violence. Perhaps there was an attempt to make this a common man as super hero vehicle — there are various references to Spenser as Batman — but there is no follow-through on that concept either. The jokey moments come across as precious, with glib quips often followed by an exceptionally ugly moment. It is not impossible to pull off this seemingly incongruent blend; the Dirty Harry movies did it brilliantly. Spenser Confidential doesn’t even try. It just lopes along, leaving a trail (and trial) of clichés.

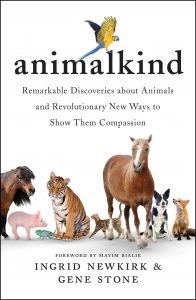

According to their sources, much of the testing on animals is of limited-to-no value given the dissimilarities of humans and animals. In addition, computer simulations are slowly replacing many areas of exploration: “In the future, the math may replace the mouse.” Finally, they encourage people to only use products and brands that are proven to be cruelty-free.

According to their sources, much of the testing on animals is of limited-to-no value given the dissimilarities of humans and animals. In addition, computer simulations are slowly replacing many areas of exploration: “In the future, the math may replace the mouse.” Finally, they encourage people to only use products and brands that are proven to be cruelty-free.

The story begins as the book’s did. Buck, a St. Bernard/Scotch collie, lives in Santa Clara, California, with his master, Judge Miller (a nice cameo by Bradley Whitford). After being stolen and shipped north, he is sold into the service of a mail-delivering dogsled team.

The story begins as the book’s did. Buck, a St. Bernard/Scotch collie, lives in Santa Clara, California, with his master, Judge Miller (a nice cameo by Bradley Whitford). After being stolen and shipped north, he is sold into the service of a mail-delivering dogsled team.