By Daniel Dunaief

The Food and Drug Administration last week approved donanemab, or Kisunla, an intravenous treatment for early stage Alzheimer’s disease, adding a second medication for mild stages of a disease that robs people of memory and cognitive function.

The monoclonal antibody drug from Eli Lilly joins Leqembi from drug makers Eisai and Biogen as ways to reduce the characteristic amyloid plaques that are often used to diagnose Alzheimer’s.

While the medications offer ways to slow but do not stop or reverse Alzheimer’s and come with potential significant side effects, doctors welcomed the treatment options for patients who are at risk of cognitive decline.

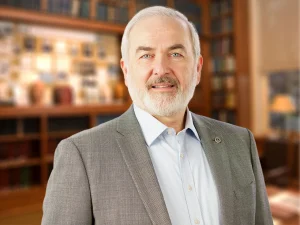

Dr. Nikhil Palekar, Medical Director of the Stony Brook Center of Excellence for Alzheimer’s Disease and Director of the Stony Brook Alzheimer’s Disease Clinical Trials Program, has been in the field for about two decades.

“Only in the last three years have I finally become quite optimistic” about new treatments, said Palekar, who is a consultant for Eisai. “We’ve had so many failures in the last few decades” with the current medications targeting the core pathologies.

That optimism comes at a time when more people in the United States and around the world are likely to deal with diseases that affect the elderly, as the number of people in the United States who are 85 and older is expected to double in the next 10 years.

The rates of Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia is about 13 percent for people between 75 and 84 and is 33 percent for people over 85 according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

The Alzheimer’s Association issued a statement welcoming the addition of Kisunla to the medical arsenal.

“This is real progress,” Joanne Pike, Alzheimer’s Association president and CEO, said in a statement. The approval “allows people more options and greater opportunity to have more time.”

To be sure, Leqembi, which was approved in June of 2023 and Kisunla aren’t a guarantee for improvement and come with some potentially significant side effects.

Some patients had a risk of developing so-called amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, which includes brain edema, or ARIA-E or hemorrhaging, or ARIA-H in the brain.

ARIA can resolve on its own, but can, in rare cases, become severe and life-threatening.

Patients taking these medications receive regular monitoring, including MRI’s before various additional treatments.

Patients are “monitored carefully” before infusions to “go over symptom checklists to make sure they don’t have neurological symptoms,” said Palekar. “If they have any symptoms, the next step is to head to the closest emergency room to get an MRI of the brain, which is the only way to know if a side effect is causing symptoms.”

Nonetheless, under medical supervision, patients who took the medication as a part of clinical trials showed a progressive reduction in amyloid plaques up to 84 percent at 18 months compared to their baseline.

The benefits for Leqembi, which is given every two weeks, and Kisunla, which is administered every four weeks, were similar in terms of slowing the effect of cognitive decline, said Dr. Marc Gordon, Chief of Neurology at Zucker Hillside Hospital in Glen Oaks.

“Neither of them is a cure for Alzheimer’s,” said Gordon. “These medications are not a home run, but at least we’re on base.”

Not eligible

Not everyone is eligible to take these monoclonal antibody treatments.

These drugs are not available for people who have progressed beyond the mild stage of the disease. Clinicians advised those who are showing potential signs of Alzheimer’s to visit their doctors before the disease progresses beyond the point where these drugs might help.

Additionally, people on blood thinners, such as Eliquis, Coumadin, and Warfarin, can not take these drugs because a micro bleed could become a larger hemorrhage.

People who have an active malignant cancer also can’t take these drugs, nor can anyone who has had a reaction to these treatments in the past. The people who might likely know of an allergic reaction to these drugs are those who participated in clinical trials.

Doctors monitor their patients carefully when they administer new drugs and have epinephrine on hand in case of an allergic reaction.

Patients with two alleles – meaning from both parents – of a variant called APOE ε4 have a higher incidence of ARIA, including symptomatic, serious and severe AIRA, compared to those with one allele or non-carriers.

If patients have this variant on both alleles, which occurs in about 15 percent of Alzheimer’s patients, Gordon and Palekar both counsel patients not to take the drug.

“We don’t think the risk is acceptable” for this patient population, Gordon said.

Ultimately, Palekar believes patients, their doctors and their families need to make informed calculations about the risks and benefits of any treatment, including for Alzheimer’s.

Beyond drugs

Palekar added that recent studies have also shown that an increase in physical exercise and activity, such as aerobic activity three times a week for 45 minutes each time, can “significantly help in patients with cognitive symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease,” he said.

After consulting with a physician to ensure that such activity is safe, patients can use a stationary bike or take walks which can benefit their bodies and their brains.

Additionally, various diets, such as the mind diet that combines the mediterranean diet and the DASH diet, which emphasize eating green leafy vegetables and berries among other things, can benefit the brain as well.

Patients also improve their cognitive health by continuing mental activity through games as well as by retaining social connections to friends, family and members of the community.

Like many other people, Palekar witnessed the ravages of Alzheimer’s first hand. As a teenager, he saw his aunt, who was smart, caring and loving, stare out the window without being able to communicate and engage in conversation as she battled the disease.

As a condition involving amyloid plaques, tau proteins, and inflammation, Alzheimer’s disease may require a combination of treatments that address the range of causes.

“There’s going to be a combined therapy,” said Gordon. “Just like when we’re treating cancer, we don’t have just one drug. It’s going to be important to figure out the sequencing and whether drugs are given sequentially or cumulatively. It has to be a multi-faceted approach.”