They have a sense of urgency that motivates those around them to push for better results. In fighting against diseases that kill millions of people every year, they are doing what they’ve done from the time they left their home country of Lebanon until they arrived at Stony Brook three years ago: They are supporting their colleagues, recruiting top talent from around the world and encouraging their staff to train and encourage the next generation of researchers.

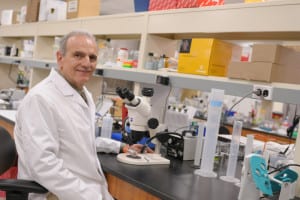

Yusuf Hannun, the director of the Cancer Center at Stony Brook, and Lina Obeid, the dean for research, continue to build a deep and talented team, adding researchers focused on curing diseases while also developing the next generation of Stony Brook scientists. The Port Times Record recognizes Hannun and Obeid as People of the Year for their day-to-day leadership, their discoveries in their labs, and their focus on the future of science at Stony Brook.

“In terms of what they are building at Stony Brook, their vision is to grow that Cancer Center into a NCI-designated Cancer Center,” said Gerard Blobe, a professor and research director at the Division of Medical Oncology at Duke University Medical Center who earned his Ph.D. in Hannun’s lab more than 20 years ago. They want to make it a “force in clinical care and research and training. They have a mission up there and I have no doubt that they’ll accomplish it.”

Blobe said the National Cancer Institute designation is just the “icing on the cake” that enables the center to seek funding for some projects. What’s more important, he said, is “what they will accomplish by getting that prize,” in building and developing Stony Brook’s research abilities.

Scientists in the same field as Hannun were quick to praise his achievements and innovation.

Discoveries by Hannun about sphingolipids, which are molecules that are involved in a range of roles, including cell division, differentiation and cell death, provided key insights.

Hannun “pushed the field into the modern age,” said Tony Futerman, the Joseph Meyerhoff professorial chair of biochemistry at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel. “He’s been innovative for 30 years in the field.”

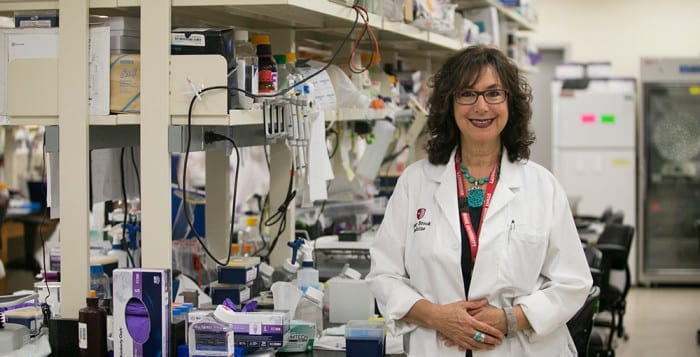

In her lab, Obeid, who is the dean for research and a professor at the Stony Brook School of Medicine, is exploring the role of enzymes that control molecules involved in cell growth and others that play a role in cell death or differentiation.

Futerman said Hannun and Obeid have been instrumental in the careers of many other scientists, developing talented and dedicated researchers who have also made significant contributions.

“They are excellent mentors of younger people,” he said. “There’s a whole school of former post docs who went on to get independent positions. This speaks to their mentorship. … They push young people into leadership positions.”

Those who have worked for Obeid and Hannun in the past suggested that they offered the kind of guidance, discipline and approach that was applicable in and outside the lab.

“Part of [Hannun’s] success is he’s very good at planning,” said Supriya Jayadev, who was a graduate student in Hannun’s lab at Duke and is now the executive director of Clallam Mosaic in Port Angeles, Washington. “He plans out an experiment such that it works the first time.”

Corinne Linardic, Hannun’s first graduate student, said, “I remember him saying, ‘It’s important not to look where the light is, but to try to look into the dark and turn the light on. … I thought that was very brave.”

Linardic, who is now an associate professor of pediatrics at Duke University School of Medicine, also said she felt fortunate to work with Obeid.

“It was extraordinary to have a female mentor as well,” Linardic said.

While they have come a long way from the beginning of their careers and their family, Hannun and Obeid have kept a consistent focus on the potential clinical benefits of their research.

“They get the translational aspects,” Futerman said. “When [Hannun] moved to Stony Brook to head the Cancer Center, that was one of the aims for his move, to be in a position where he can apply basic science to translational research.”

Futerman said Hannun and Obeid deserve recognition in the Long Island and scientific communities.

“They are considered leaders,” Futerman said. “They contribute a lot to the academic community.”