By Daniel Dunaief

In the second of a two-part series, Times Beacon Record News Media will feature the work of Eric Yee, who, like his wife Felicia Allard who was featured last week, is joining the Pathology Department at Stony Brook University.

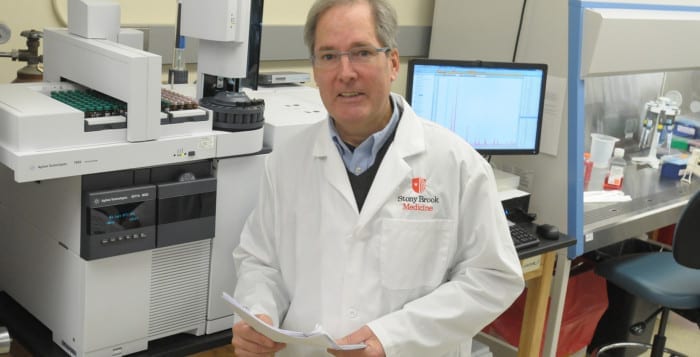

Eric Yee

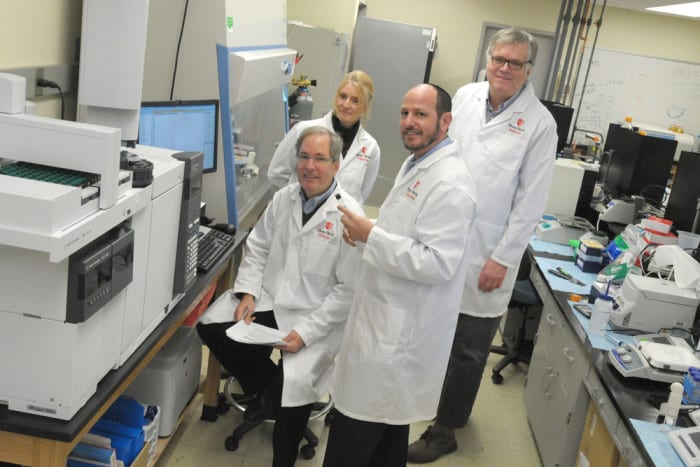

Eric Yee, who started as an Associate Professor and Director of Surgical Pathology at Stony Brook Renaissance School of Medicine on July 1, described the focus of his scientific research as translational.

He consults with and helps science researchers put together ideas for experiments, while he and his wife Felicia Allard focus on bringing that work into the clinical setting.

“We provide expertise mainly in clinical gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary pathology,” Yee explained in an email. “We also give insights and perspectives as practicing pathologists to help [with the] analysis of data and how that data in the lab or in animal models may be relevant to clinical medicine.”

Yee completed a gastrointestinal pathology fellowship, working on collaborative research projects and publishing manuscripts with investigators.

As one of the newest members of the staff at Stony Brook, he has worked on some studies looking at certain kinds of inflammatory diseases in the liver. He collaborated with senior investigator Zhenghui Gordon Jiang of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center to look at mediators of inflammation in the disease steatohepatitis. He has also worked on different cancer research projects, which is part of the appeal of Stony Brook.

Stony Brook has “important pancreatic research,” Yee said, adding that. Pathology Department Chair Ken Shroyer is a “renowned investigator whose research team has done great work that has led to important insights into pancreatic cancer biology.”

Pancreatic cancer is of particular interest to Yee in his clinical work and he hopes to explore the variety of research expertise at Stony Brook, to support ongoing efforts and to develop projects of his own.

Relocating to Stony Brook from the College of Medicine at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, where Allard and Yee both worked in the Pathology Department, took some convincing for both of the scientists.

“We were very happy in Little Rock and purchased a home in Arkansas two years prior and were just starting to set down roots,” Yee described in an email. “We made lifelong friendships and very much enjoyed the camaraderie among our peers and other departments.”

Yee and Allard had no plans to leave as they approached their third year and were hesitant to move.

In his first visit, Yee said he was impressed with the amount of research in the Stony Brook department, which, he said, has more researchers compared to other institutions of similar size.

On the other side, however, Yee said he and Allard had to reconcile the higher cost of living in New York. They also weren’t eager to make too many moves in their career, especially when they were happy in Arkansas.

Even after the first visit, Yee said he was hesitant to make a move, which would require time to settle in, build relationships, find a home, learn a new system, and find new opportunities, among other challenges..

Shroyer was “very understanding of my hesitation,” Yee explained. “He’s been one of my mentors since medical school and knew exactly where I was coming from.

Clinically, the couple also believed in the potential for career growth.

“There’s a lot of energy in the department,” Yee said. He also appreciated the opportunity to be the Director of Surgical Pathology, where he could shape the operations that support the clinical mission. He would like to optimize the department by specialization, creating a sub-specialty model.

“This is something I want to do to increase the efficiency in the department,” Yee explained. “I’m hoping as we sub-specialize that we make our clinical work flow more efficient” which will create more consistency. “Part of what I’d like to do is to help [Shroyer] create a department where it’ll allow the clinical faculty to thrive.”

Yee thinks any work efficiencies will provide researchers with more time to build on their teaching efforts, and to develop new lectures and teaching models.

Yee will measure his success through a comprehensive report that includes an analysis of the efficiency of the response to clinical needs. He hopes to create a system that will enable the success of the entire anatomic pathology division. He will also become actively engaged in the academic mission, which is measured in the number of publications as well as in staff appointments to editorial boards or major national societies.

“The more people we can get into the national arena the better it is for the institution,” Yee said. These contributions bring good public relations and expertise to the institution.

Yee and Allard will also contribute to Stony Brook through their efforts in education.

Yee believes the school has an advantage in telepathology and distance learning. He believes the Department of Bioinformatics led by Dr. Joel Saltz facilitates telepathology and distance learning.

With the uncertainty caused by COVID-19, Yee believes maintaining social distancing and finding innovative ways for communication and education will provide valuable alternatives to communicate and collaborate. Radiology has had digital methods in place to send MRIs and CAT scans for a longer period of time than pathologists, who still produce glass slides.

“There will always be some challenges and limitations that are unique to pathology,” Yee suggested.

A native of San Francisco, where he and his older brother, who now works in Boston, grew up, Yee was interested in medicine during the middle of his college career.

Yee and Allard met in medical school and, among numerous other parts of their lives they have in common, discovered they were both fans of the Star Wars films. Early on when they were dating, the pathology couple saw Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith together.

Yee enjoys tennis, table tennis, riding road bikes and hiking. He has also developed an appreciation for bird watching, which has allowed him to practice amateur photography.

The couple also shares an interest in music, as Yee grew up playing the piano, while Allard played the trumpet.

When he was in medical school, Yee published his first paper with Shroyer. He has remained in touch with the pathology chair over the years and appreciates the advice Shroyer has offered.

Yee described Shroyer as an “inspirational leader” and appreciates his energy, selflessness and passion, among other qualities.