By Elizabeth Kahn Kaplan

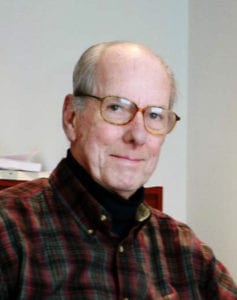

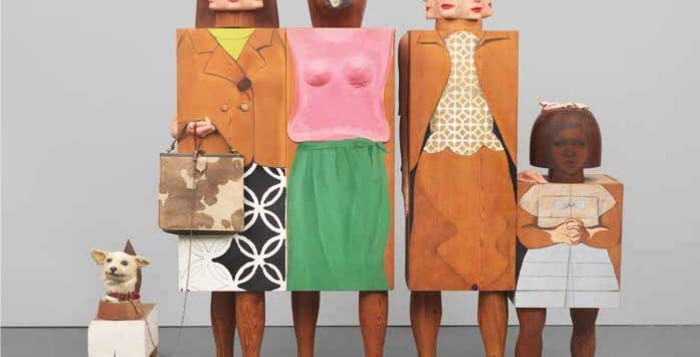

St. James resident Philip F. Palmedo has produced a beautifully written and generously illustrated book on a subject that has intrigued, delighted, and frightened children and adults from ancient days to the present: therianthropy, the mythological ability of humans to metamorphose into animals or animal-human hybrids.

“The concept of the therianthrope can catalyze the creative imagination,” writes Palmedo.

The first that we know of is the Upper Paleolithic Lion-Man carved out of woolly mammoth ivory some 40,000 years ago. While we can only conjecture why it was created, we know that more recent animal-headed deities like the jackal-headed Egyptian god Anubis played important roles some 5000 years ago in weighing the worth of a person after death.

In the Hindu pantheon, elephant-headed, four-armed Ganesha is widely revered as a bringer of good luck; in Christian art winged angels abound, by turns avenging and comforting. In the 20th century, the ancient Greek legend of the fearsome Minotaur, a man with the head and tail of a bull, served as Pablo Picasso’s “allegorical alter-ego . . . with many of his etchings, paintings, and sculptures featuring this mythical bull-man.”

Imaginative minds past and present have created talking animals, from the wicked snake in Genesis that tempted Eve in the Garden to the Cowardly Lion in The Wizard of Oz, Disney’s Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, and lovable Big Bird of Sesame Street.

Imaginative minds past and present have created talking animals, from the wicked snake in Genesis that tempted Eve in the Garden to the Cowardly Lion in The Wizard of Oz, Disney’s Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, and lovable Big Bird of Sesame Street.

Shape-shifting, the ability to change from human to animal or to an inanimate object, abounds in Greek mythology. One rather improbable example is that of the god Zeus changing into a swan to seduce Leda. In another example, as retold by the ancient Roman poet Ovid, the beautiful river nymph Daphne was “shapeshifted” by her father, morphing into a laurel tree to defeat the unwelcome advances of Apollo, the Greek god of the arts. The sadder but wiser Apollo paid tribute to her by adopting the laurel wreath as his crown.

In America, therianthropy is on display in The Wolf Man horror films, from Lon Chaney’s 1941 portrayal to Benicio del Toro’s in 2010. More recently, the widely consumed Harry Potter tales spun by prolific British writer J. K. Rowling charmed children and adults with a talking bird, Hedwig, and with Firenze, the centaur who rescued Harry from the villain Voldemort.

Centaurs, mythic creatures with the upper body of a human and the lower body and legs of a horse, are the land complement to creatures with human upper torsos ending in huge fish tails — mermen and the alluring mermaids sighted by lonely mariners whose names derive from the French word for the sea, La mer. Palmedo’s chapter, Merpeople, is richly illustrated with examples in art from 6000 BC Serbia and 4th century BC Greece to 19th and 20th century India, Japan, Great Britain, and Denmark, including the bronze sculpture The Little Mermaid that overlooks the harbor in Copenhagen. Based on Hans Christian Andersen’s tale published in 1837, that fable might bring tears to one’s eyes.

On the other hand, Norman Rockwell’s 1955 Saturday Evening Post cover, The Mermaid, can only make us chuckle with its depiction of an elderly fisherman hauling a beautiful mermaid home, her long elegant tail protruding from the large wooden fish trap on his back.

This elegant, art-illustrated book written with clarity, printed on glossy paper, will entertain and enlighten. It can be purchased from Amazon.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

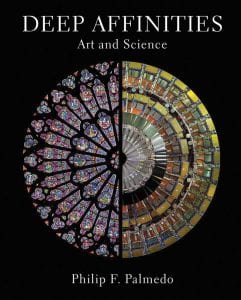

A Ph. D. in Nuclear Engineering from M.I.T., Philip F. Palmedo, former head of the Energy Policy Analysis Division at Brookhaven National Laboratory, was for many years Chairman of the Washington-based International Resources Group, which he founded. A former Trustee of Williams College in Massachusetts, where he majored in Physics and Art History as an undergraduate, Palmedo formed and was President of the Long Island Research Institute. He also serves on the MIT Council for the Arts, and is a fellow of the Williams College Museum of Art. Palmedo’s previous book was Deep Affinities: Art and Science.

Two Three Village residents, educators at the top of their profession — Jacqueline Grennon Brooks, professor emerita of Teaching, Learning and Technology, Hofstra University, and her spouse Martin Brooks, executive director of Tri-State Consortium, an association of over 40 school districts in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut — agree that the key to whether or not learning takes place is not how information is delivered but if knowledge is constructed. Whether it is a teacher or a book or a computer that provides a formal lesson, the students must connect the lesson to what they already know or have experienced for true learning to occur.

Two Three Village residents, educators at the top of their profession — Jacqueline Grennon Brooks, professor emerita of Teaching, Learning and Technology, Hofstra University, and her spouse Martin Brooks, executive director of Tri-State Consortium, an association of over 40 school districts in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut — agree that the key to whether or not learning takes place is not how information is delivered but if knowledge is constructed. Whether it is a teacher or a book or a computer that provides a formal lesson, the students must connect the lesson to what they already know or have experienced for true learning to occur.