By David Dunaief, M.D.

Many people worry about getting enough protein, when they really should be concerned about getting enough fiber. Most of us — except perhaps professional athletes or long-distance runners — get enough protein in our diets. Protein has not prevented or helped treat diseases in the way that studies illustrate with fiber.

As I mentioned in my previous article, Americans are woefully deficient in fiber, getting between eight and 15 grams per day, when they should be ingesting more than 40 grams daily.

In order to increase our daily intake, several myths need to be dispelled. First, fiber does more than improve bowel movements. Also, fiber doesn’t have to be unpleasant.

The attitude has long been that to get enough fiber, one needs to eat a cardboard box. With certain sugary cereals, you may be better off eating the box, but on the whole, this is not true. Though fiber comes in supplement form, most of your daily intake should be from diet. It is actually relatively painless to get enough fiber; you just have to become aware of which foods are fiber rich.

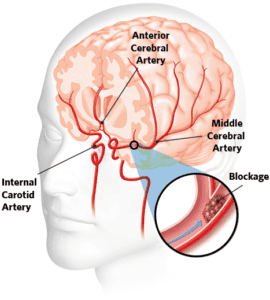

Fiber has very powerful effects on our overall health. A very large prospective cohort study showed that fiber may increase longevity by decreasing mortality from cardiovascular disease, respiratory diseases and other infectious diseases (1). Over a nine-year period, those who ate the most fiber, in the highest quintile group, were 22 percent less likely to die than those in lowest group. Patients who consumed the most fiber also saw a significant decrease in mortality from cardiovascular disease, respiratory diseases and infectious diseases. The authors of the study believe that it may be the anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant effects of whole grains that are responsible for the positive results.

Fiber has very powerful effects on our overall health. A very large prospective cohort study showed that fiber may increase longevity by decreasing mortality from cardiovascular disease, respiratory diseases and other infectious diseases (1). Over a nine-year period, those who ate the most fiber, in the highest quintile group, were 22 percent less likely to die than those in lowest group. Patients who consumed the most fiber also saw a significant decrease in mortality from cardiovascular disease, respiratory diseases and infectious diseases. The authors of the study believe that it may be the anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant effects of whole grains that are responsible for the positive results.

Along the same lines of the respiratory findings, we see benefit with prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with fiber in a relatively large epidemiologic analysis of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study (2). The specific source of fiber was important. Fruit had the most significant effect on preventing COPD, with a 28 percent reduction in risk. Cereal fiber also had a substantial effect but not as great.

Does the type of fiber make a difference? One of the complexities is that there are a number of different classifications of fiber, from soluble to viscous to fermentable. Within each of the types, there are subtypes of fiber. Not all fiber sources are equal. Some are more effective in preventing or treating certain diseases. Take, for instance, a February 2004 irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) study (3).

It was a meta-analysis (a review of multiple studies) study using 17 randomized controlled trials with results showing that soluble psyllium improved symptoms in patients significantly more than insoluble bran.

Fiber also has powerful effects on breast cancer treatment. In a study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, soluble fiber had a significant impact on breast cancer risk reduction in estrogen negative women (4). Most beneficial studies for breast cancer have shown results in estrogen receptor positive women. This is one of the few studies that has illustrated significant results in estrogen receptor negative women.

The list of chronic diseases and disorders that fiber prevents and/or treats also includes cardiovascular disease, Type 2 diabetes, colorectal cancer, diverticulosis and weight gain. This is hardly an exhaustive list. I am trying to impress upon you the importance of increasing fiber in your diet.

Foods that are high in fiber are part of a plant-rich diet. They are whole grains, fruits, vegetables, beans, legumes, nuts and seeds. Overall, beans, as a group, have the highest amount of fiber. Animal products don’t have fiber. Even more interesting is that fiber is one of the only foods that has no calories, yet helps you feel full. These days, it’s easy to increase your fiber by choosing bean-based pastas. Personally, I prefer those based on lentils. Read the labels, though; you want those that are solely made from lentils without rice added.

If you have a chronic disease, the best fiber sources are most likely disease dependent. However, if you are trying to prevent chronic diseases in general, I would recommend getting fiber from a wide array of sources. Make sure to eat meals that contain substantial amounts of fiber, which has several advantages, such as avoiding processed foods, reducing the risk of chronic disease, satiety and increased energy levels. Certainly, while protein is important, each time you sit down at a meal, rather than asking how much protein is in it, you now know to ask how much fiber is in it.

References:

(1) Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(12):1061-1068. (2) Amer J Epidemiology 2008;167(5):570-578. (3) Aliment Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2004;19(3):245-251. (4) Amer J Clinical Nutrition 2009;90(3):664–671.

Dr. Dunaief is a speaker, author and local lifestyle medicine physician focusing on the integration of medicine, nutrition, fitness and stress management. For further information, visit www.medicalcompassmd.com or consult your personal physician.

YIELD: Makes 10 servings

YIELD: Makes 10 servings