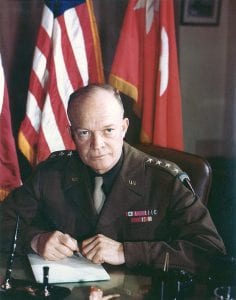

The Story of Eisenhower Prior to D-Day, 1944

By Rich Acritelli

“The question is just how long can you keep this operation on the end of a limb and let it hang there.”

These were the words of General Dwight D. Eisenhower in the hours before the June 6 D-Day amphibious and air drop landings. While Eisenhower was surrounded in this meeting by noted leaders like General Omar N. Bradley and Field Marshall Bernard L. Montgomery, the immense strain of making this momentous decision was on the shoulders of this native of Abilene, Kansas. Through the poor weather conditions that almost derailed the landings, Eisenhower was concerned that if this massive forces waited any longer, it was possible that the Germans would have learned of the true landings were to be at Normandy and not Calais, France. Judging the factors that were against his naval, air and land forces, Eisenhower simply stated, “Ok, we’ll go.”

As Eisenhower feared the heavy losses that were expected to penetrate the “Atlantic Wall,” he was confident of the Allied plans to achieve victory against the Germans. While German leader Adolf Hitler made numerous military miscalculations, one of his worst was the full belief that Americans that lived under capitalism and democracy which could not defeat the German soldiers that were indoctrinated within Nazism. Eisenhower was representative of the average soldier from the heartland, small towns and cities of this nation that wanted to fulfill their duty, save the world from tyranny, and return home to their families.

As a young man, Eisenhower grew up in a poor, rural, and religious family. While he was a talented baseball and football player, the young man did not stand out amongst his peers as being the best. There was the belief that he had lied about his age to show that he was younger to be originally accepted into the Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, but he was turned down by this school. But Eisenhower gained a congressional appointment for an army education and he was ordered by the War Department to head to West Point in June 1911. Due to the two years of work at a creamery, Eisenhower was a bit older and experienced and the hazing that he took as a freshman was not challenging for the 21-year-old during his first semester. This Class of 1915 was one of the most highly promoted groups to graduate from West Point with over sixty officers attaining the rank of general during World War II.

Eisenhower had two main interests that stayed with him for most of his life. He was an avid card player that supplemented his low army pay with winning numerous hands against his fellow officers and like that of Ulysses S. Grant, he was highly addicted to nicotine. There are many parallels between the lives of Eisenhower and Grant, as both officers were from the mid-west, they were not from wealthy families, and as Eisenhower was a strong football player, Grant was one of the finest horseback riders in the army. Both men graduated in the middle of their classes at West Point, though much of this was due to a lack of interest that they demonstrated with some of their studies. The other key attribute was that they were extremely likable men that were easy to approach, they used common sense to make difficult decisions and they were not swayed under highly stressed war time situations.

Athletic promise and some mischievous was seen when Eisenhower played minor league baseball under an assumed name during the summer months when he returned home to Kansas. Eisenhower did not admit to playing professional baseball until he was President some decades later. During his years at the academy, Eisenhower was a talented football player that suffered a career ending knee injury. He was fortunate that the doctor wrote a medical report that stated he was physically able to complete the rigors of his army responsibilities. In September 1944, during the Operation Market Garden air drops into the Netherlands, Eisenhower was unable to leave his plane during a meeting with Montgomery because he still had severe pain from this chronic knee ailment.

For the two years leading to Woodrow Wilson’s declaration of war in 1917 against Germany, Eisenhower served in the infantry and was a football coach at a prep school near his San Antonio army base. During this early period that Eisenhower showcased his coaching knowledge, many of the American soldiers kept a watchful eye on the border after it was attacked by Mexican bandit Pancho Villa. There were also pressing issues that the United States would be pushed into the Great War that raged in Europe. Unlike other older World War II officers, Eisenhower had no combat experience during World War I. He distinguished himself running a tank training center in Camp Colt Pennsylvania that was outside of Gettysburg. For his efforts, Eisenhower was promoted to the rank of colonel, but the fighting ended as he was preparing to ship out. Eisenhower was an extremely capable officer, but he believed for the next twenty years that he would never have the chance to prove his abilities under enemy fire.

After WWI ended, the National Defense Act of 1920 drastically cut back the army promotions that were seen during the war and Eisenhower was demoted to a permanent rank of major. At this time, Eisenhower convoyed across the nation from Maryland to California and he observed the poorly connected roads that led from cities to the rural areas. Later as President this knowledge pushed him to build more infrastructure projects during the 1950’s. Living at Fort Meade, he also met George S. Patton, where both men and their families became good friends. Eisenhower enjoyed listening to war time exploits of Patton and both men had endless discussions on military tactics.

It has been stated that these officers were not friendly during and after World War II, but this was far from true. These two men were completely different from each other, Patton was extremely wealthy, and he lived a vastly different life than Eisenhower. Patton furnished his house with furniture from France, had sports cars, servants and the best polo horses. Eisenhower had to rely on the poor military pay and he took furniture from the nearest dump that he refurnished.

There were many other connections that surely aided the professional development of Eisenhower. During World War I, General Fox Connor was a key planner that pushed American troops into the first battles against the Germans on the Western Front. He was a trusted leader that listened to the early military doctrine that these younger officers sought within the next major war. Eisenhower credited Patton with meeting Connor whom he considered to be a teacher and father figure that cultivated his earliest approach to leadership. Connor was a well-rounded officer that understood the need to work well with allies and to establish the most efficient military organization. These traits were all exhibited by Eisenhower’s command style during World War II and Connor advised his protégé to gain a position that enabled him to work with the brilliance of George C. Marshall. Although both men knew of each other and had brief encounters, they would not have any major connection for some twenty years until the start of World War II in 1939.

Whereas Eisenhower did not serve in France during World War I, he had the unique opportunity to visit the battle sites with General John J. Pershing. The Battle Monuments Commission was established in 1923 to identify the different places that Americans fought from 1917-1918. While this was at first seen by Eisenhower as a limited position, he was in the presence of Pershing and he was able to show his considerable talents with his writing. Like that of the other senior officers, Pershing was extremely pleased with the ability of Eisenhower to accurately present the American contributions to this war. Several years later when Pershing wrote his own memoirs, he asked Eisenhower to review the portions of this book that pertained to the battle sites that he commanded. In an interesting twist of fate, Eisenhower would again see these locations as the senior Allied commander during World War II.

In 1926, Eisenhower entered the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Missouri. Armed with the knowledge of the terrain around Gettysburg, he was able to decisively speak about the tactics of this Civil War battle that made him shine amongst his fellow students. Graduating first in his class, he was given some help by his friend Patton who provided his notes to Eisenhower from his own time at this school. By the end of the 1920’s, Eisenhower completed the prestigious education through the War College. This school was established to train our future army leaders and Eisenhower was evaluated as being one of the most superior officers within his class. When he graduated his paper on mobilization was sent to the War Department, and some ten years later, his ideas were used during the tumultuous mobilization, training, and planning years of 1939-1941.

In 1930, General Douglas MacArthur became the youngest Army Chief of Staff to hold this position. While promotions were slow for Eisenhower, he was widely liked, and he continued to work with the best minds in the army. As he respected the experience of MacArthur, Eisenhower did not like the the man’s ego and often clashed with some of his rash ideas. In 1932, World War I veterans widely suffered from the Great Depression and they descended on the capital to wage a massive protest. They sought an early payment of bonds that were promised to them for their service during the war. Army veterans organized themselves into groups, lobbied politicians, and slept on the lawn of the Capital Building.

After there were hostile actions between the police and veterans, Hoover ordered MacArthur to use limited force to push these people out of Washington D.C. Although MacArthur led many of these men, he was convinced that there were communist radicals intermixed within the protesters ranks and that they had to be driven out of the capital by excessive force. Eisenhower was appalled MacArthur’s action who he believed severely misinterpreted his orders from Hoover. As he later traveled with MacArthur to live in the Philippines to run their military, by 1939, he requested a transfer back to the states. He was burnt out for handling the numerous responsibilities of working for MacArthur and he wanted a fresh start away from this demanding officer. At this time, his son John asked him about entering West Point, Eisenhower stated that the army was good to him, but he would shortly be retiring as a colonel.

With World War II starting in Europe, General George C. Marshall was appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt the position of Army Chief of Staff. It was known that Marshall kept an eye on promising officers that he was bound to place in key leadership positions. While he barely knew Eisenhower, Marshall was giving a glowing recommendation by General Mark Clark on his effectiveness. At one point, Eisenhower believed that Patton was destined for the highest rank and responsibility. While Marshall respected Patton, Eisenhower was one of the few officers that understood the big military picture, he respected his planning during the 1941 military maneuvers, and his ability to solve complex problems with little help from others.

From 1941-1944, Eisenhower in quick time went from an untried senior officer in battle, to organizing the greatest coalition ever assembled to defeat Hitler’s forces in Europe. As Eisenhower pondered attacking Normandy in the hours before the June 6, 1944 D-Day landings, his many decades of service, experiences, and relationships helped him make this momentous decision. Always armed with the will to succeed for this nation and the world against this totalitarian power, Eisenhower’s presence some seventy six years ago made the tremendous decision to bring the beginning of the end to Hitler’s terrible rule on the European mainland.

Rich Acritelli is a social studies teacher at Rocky Point High School and an adjunct professor of American history at Suffolk County Community College.