By Patrice Domeischel

It was inevitable. Life for any bird is fraught with perils. That Flaco, the Eurasian Eagle-Owl illegally released over one year ago from the confines of his lifetime home in the Central Park Zoo would survive despite having no life experience outside his enclosure, would be nothing short of a miracle.

We had all waited, expecting the worst. Would he make it? The tentative answer appeared to be “Yes”. And it did seem that he just might have bucked the odds as instinct kicked in, and he mastered the unfamiliar, urban environment.

Birders, photographers, city residents, tourists, all wanted a glimpse of the famous escapee owl. He delighted all who viewed him as he perched at some of his regular Central Park haunts, and later in the Upper West Side neighborhoods of Manhattan. Flaco had become a symbol of freedom, surprising and eluding those who sought to bring him back to the zoo’s safe confines. To New Yorkers and out-of-towners alike, some whom had never seen any owl, Flaco was an avian celebrity.

Then our greatest fears were realized. Flaco became one of up to one-billion birds EACH year that die in the United States alone after flying into windows, his death determined to have been caused by “traumatic impact.” And although a necropsy report indicated Flaco’s good condition, his weight only slightly less than when last taken at the zoo, he may also have been exposed to infectious diseases like West Nile Virus or Avian Influenza, and/or toxins including rodenticides that would have weakened him, contributing to the strike.

Now Flaco has become another painful window-collision statistic. His passing shines a harsh light on this serious issue. Window strikes can occur at any time of year, but take place most often during spring and fall migration when billions of birds travel to and from breeding and wintering grounds. Strike incidents occur with great regularity when birds collide with the highly reflective glass used in building construction. Birds see the reflections in these panes as a continuation of the natural landscape and attempt to fly through them. Most collisions occur with the windows of one-and-two story buildings; many are residential homes.

But there may be a silver lining to this tragedy. The urgent need to protect birds from death caused by window strikes has already resulted in legislation in New York City that requires the use of bird-friendly materials in new construction. The City also has a lights-out requirement for city-owned and city-managed buildings. In Albany also, a bill is now on the table that requires the incorporation of bird-friendly designs into new or altered-state buildings in New York State. Maybe Flaco’s needless end will help to propel the bill to completion and law.

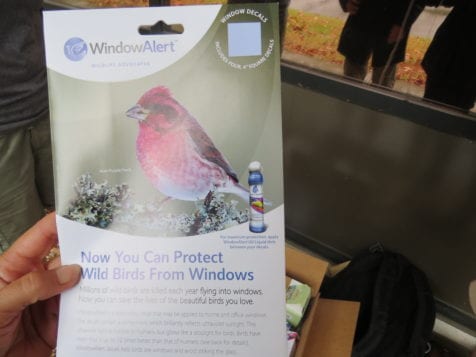

What can you do? We all have the power to make a difference. We can prevent window-strike collisions at our own homes and in the community. Simply affixing decals that reflect ultraviolet sunlight, or that create visual interference, on problem windows can dramatically cut strike numbers. Birds detect the stickers, recognize something to avoid, and fly elsewhere.

Flaco will be remembered always in the hearts of New Yorkers; we mourn his loss. But his name will live on in the meaningful and important legislation now on the table in Albany, a bill renamed the FLACO ACT: “Feathered Lives Also Count,” after this iconic and charismatic raptor.

Note: Do you know of a building prone to window strikes? Let us know at: [email protected].

Learn more at these and other websites:

Fatal Light Awareness Program (FLAP)

Author Patrice Domeischel is a board member of the Four Harbors Audubon Society.