By Daniel Dunaief

Many plants are in an arms race akin to the developers of skyscrapers eager to get the most light for their prized penthouse apartments. Only, instead of trying to collect rent from well-heeled humans, these plants are trying to get the most sun, from which they create energy through photosynthesis.

Plants are so eager to get to the coveted sunlight that the part growing towards the light sends a distress signal to the roots when they are in the shade. While that might help an individual plant in the short term, it can create such shallow and ineffective roots that the plant becomes vulnerable to unfavorable weather. They also can’t get as many nutrients and water from the ground.

This is problematic for farmers, who want plants that grow in the sun, but that don’t sacrifice the development of their roots in the shade. Ullas Pedmale, Assistant Professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, is working to lend a hand.

Pedmale, who recently published research in the journal Plant Physiology, is studying the signals the shoots, or the parts of the plants either in the sunlight or the shade, send to the roots.

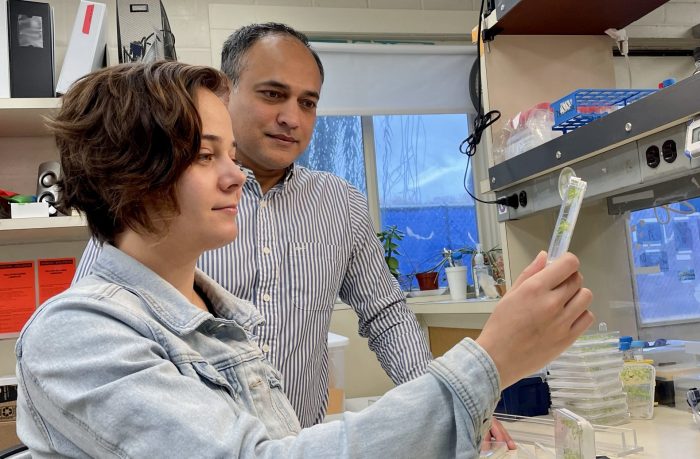

Pedmale and postdoctoral researcher Daniele Rosado, who is the first author on the recent paper, explored the genes that turned on in the roots of the model plant Arabidopsis and tomato plants when these plants were in the shade.

When plants are in the shade, they “prioritize shoot growth and try to outcompete the neighboring plants,” said Rosado. “That’s when root development is compromised.”

Among the genes that are active when plants are in the shade is a family of genes called WRKYs, which affect gene expression and cause stunted growth in the roots.

WRKY genes respond to stress. Keeping WRKY genes on all the time, even when a plant is in the sun, caused stunted growth of the roots. WRKY proteins turn on or off other genes.

This can be problematic for farmers, who tend to try to increase yield by putting more plants in an area. At that point, the plants shade each other, which is “bad for the root system. If we can find a way to get the roots to grow normally, we can potentially increase yield,” Rosado said.

This could also remove more carbon dioxide from the air and store it in the developing roots, helping to mitigate the effect of global warming. “Our study can give a roadmap on how to make longer, deeper roots,” Pedmale said.

At this point, researchers still don’t know how the plant transfers information about the amount of sunlight it receives in the green chloroplasts where photosynthesis occurs to the WRKY genes, which are in the nucleus.

Researchers have been studying the shade response in the shoots of plants for over five decades. They have not, however, focused as much attention on the effect of less sunlight on the roots.

“We want to tackle this problem,” Pedmale said.

WRKY genes are a generalized stress signal, which is not just involved when a plant isn’t getting enough light. They are also turned on during pathogen attacks, stress and amid developmental signals.

Indeed, plants in the shade that have turned on these signals are especially vulnerable to attacks. Caterpillars, for example, can eat most of a shaded plant because the plant is so focused on growing its shoot that its defenses are down.

When that same plant is in the sunlight, it is more effective at defending itself against caterpillars.

At this point, Pedmale doesn’t know whether these genes and signals occur across a broad species of plants beyond tomatoes and Arabidopsis. He and others are hoping to look for these genes in grasses and grains.

Pedmale is also searching for other signals between the shoot and the root. “Plants are masters of adaptation,” he said. “They might have redundant systems” that signal for roots to slow their growth while the shoots tap into the available energy to grow.

Plants may also have natural molecules that serve as brakes for the WRKY signal, preventing the shoot from taking all the available energy and rendering the plant structurally fragile.

A scientist at CSHL for five years, Pedmale came to the lab because of the talent of his colleagues, the reputation and opportunity at CSHL and the location.

Born and raised in Bangalore, India, Pedmale enjoys reading fiction and autobiographies and wood working when he’s not in the lab. He recently made a book shelf, which provides him with a chance to “switch off” from science, which, he said, is a 24-hour job. He has taken wood pieces from his workshop and brought them to PhD classes at CSHL, where he can show them plant biology and genetics at work.

Pedmale and his wife Priya Sridevi, who also works at CSHL, have a mini golden doodle named Henry.

A native of São Paulo, Brazil, Rosado is married to plant biologist Paula Elbl, who is the co-founder of a start up called GALY, which is trying to produce cotton in a lab instead of in a field.

Rosado is the first in her family to attend a public university. She has been working in Pedmale’s lab for two years and plans to continue her research on Long Island for at least another year.

Rosado knew Pedmale had worked as a post doctoral researcher in the lab of celebrated plant biologist Joanne Chory at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies. She met Pedmale at a plant conference, where she expressed an interest in his research.

Longer term, Rosado hopes her research has a broader impact.

“If I’m lucky, I’ll be able to see the fruits of my work being applied to make a difference and help feed people,” she said.

As for his work, Pedmale is eager to understand and use the signals from one part of a plant to another, given that the plant lacks a nervous system. “Once we can understand their language,” he said, “we can manipulate it to increase yield.”