Typhoid fever broke out in Port Jefferson in 1919, 1921 and 1924, sickening scores of villagers, claiming the lives of others and revealing shortcomings in the public health system.

Although uncommon in the United States today, typhoid fever is contracted by eating food or drinking beverages that have been handled by someone who is shedding Salmonella Typhi or if sewage contaminated with the bacteria gets into the water used for washing food or drinking.

The symptoms of typhoid include sustained fever, weakness, stomach pain, headache, diarrhea or constipation, cough and loss of appetite.

The communicable disease struck Port Jefferson during September and October 1919, resulting in 29 cases and one death. The State Health Department concluded that the outbreak was probably due to the “infection of the milk supply by a typhoid carrier.” Officials who investigated the epidemic found other unsanitary conditions in Port Jefferson.

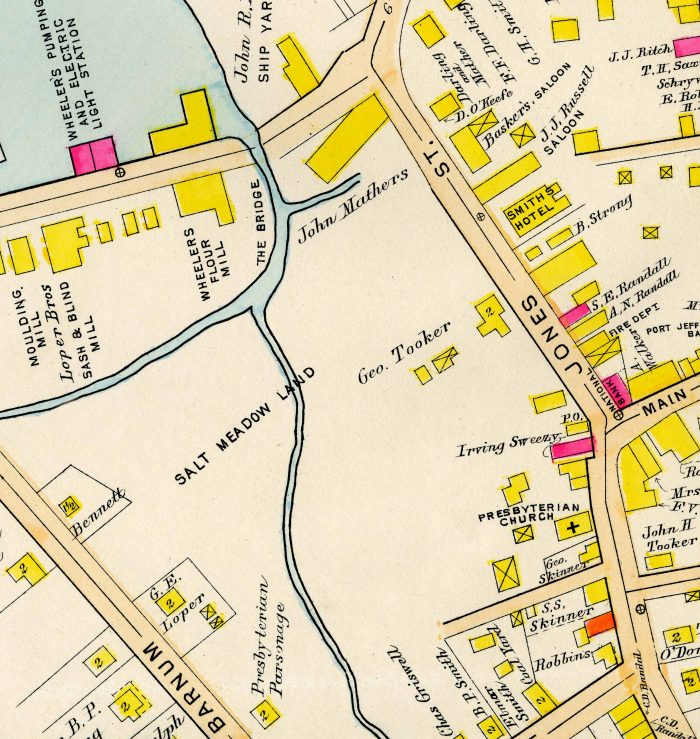

Sewage was disposed in the village’s downtown by surface drains which emptied on the salt meadows located west of Jones Street, now Main Street. The marshes flooded during high tide, carried human waste over a wide area and polluted soil and water.

The salt meadow land, referred to as the “swamp section” in local parlance, was used as a public dump, known for its horrible stench and avoided by villagers during low tide when the unsightly filth hidden by high water was exposed.

As early as 1894, members of the Ladies Village Improvement Society had urged Brookhaven Town to build modern sewers in Port Jefferson, but a new system was still not in place during the 1919 typhoid outbreak.

The dread disease returned to the village in fall 1921, left 14 dangerously ill and took the life of prominent Port Jefferson businessman Gilbert E. Loper. Once again, a dairy employee was suspected of being a typhoid carrier.

Charles L. Bergen, former chief of the Port Jefferson Fire Department, fell victim to typhoid in August 1924 when the disease struck the village and sickened 31 others. Health officials surmised that the typhoid outbreak was likely “milk-borne,” adding that the offending milk was unpasteurized and that local dairies were not regularly inspected.

The epidemic also showed that Port Jefferson was unprepared to handle the surge of typhoid victims. St. Charles Hospital then specialized in the care of disabled children and Mather Hospital was yet to open.

The Catholic sisters from the Daughters of Wisdom had graciously proposed to establish an annex on the grounds of St. Charles Hospital for typhoid sufferers alone. Out of an abundance of caution, their kind offer was not accepted because there was a dairy nearby the planned site.

When a critically ill patient from Port Jefferson was transported to a private hospital in Patchogue for medical treatment, some of the latter’s merchants decried the move, contending it might frighten away summer vacationers during the height of the tourist season.

Jacob Dreyer, editor of the Port Jefferson Times, attacked the Patchogue Argus, alleging that its slanted coverage of the typhoid outbreak was no more than an attempt to boost Patchogue at the expense of its stricken sister village.

The Port Jefferson Business Men’s Association was also concerned about the impact of the outbreak on the local economy, arguing that the metropolitan newspapers had exaggerated conditions in the village and that the negative publicity had dampened sales in Port Jefferson.

The city papers countered that both the Port Jefferson Echo and Port Jefferson Times had suppressed news of the epidemic and sugarcoated the harsh reality of the outbreak.

As no new typhoid cases were reported in Port Jefferson and life returned to normal in the village, there were calls for a county hospital, model health laws and full-time health officers.

The epidemic also stoked long-simmering tensions between Patchogue and Port Jefferson and revived calls for Port Jefferson’s incorporation and the village’s right to govern independent of Brookhaven Town.

More important, the outbreak led to improvements in Port Jefferson’s sewerage system, frequent inspections of local dairies, the filling in of the village’s lowlands and other prevention measures, effectively ending the scourge of typhoid fever in Port Jefferson.

Kenneth Brady has served as the Port Jefferson Village Historian and president of the Port Jefferson Conservancy, as well as on the boards of the Suffolk County Historical Society, Greater Port Jefferson Arts Council and Port Jefferson Historical Society. He is a longtime resident of Port Jefferson.