By Daniel Dunaief

Even over 23 years after first responders raced to the smoldering site of the World Trade Center terrorist attacks, many emergency crews continue to battle the effects of their exposure.

With a combination of toxic aerosolized particles infusing the air, first responders who didn’t wear personal protective equipment and who had the highest degree of exposure have suffered from a range of symptoms and conditions.

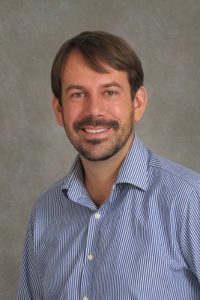

In a recent study of 35 World Trade Center first responders in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, lead author Sean Clouston, who is a Professor in the Department of Family, Population and Preventive Medicine in the Renaissance School of Medicine, found evidence of amyloid plaques, which are often linked to Alzheimer’s Disease.

The paper links exposure to a neurodegenerative protein.

Research with World Trade Center first responders not only benefits those who worked tirelessly to try to find survivors and to restore the area after the attack, but also could help other people who inhale aerosolized toxins.

Indeed, such research could help those who are spending hours battling the ongoing wildfires in Los Angeles, which have been consuming forests and trees, homes and commercial buildings, at a furious and uncontrolled pace.

People have a feeling that fresh air is safe, but what scientists have learned from their studies of the World Trade Center first responders is that “just being six feet away from a pile of rubble that’s smoldering, even if you can’t see that it’s dangerous, doesn’t mean it isn’t,” said Clouston. “There is at least some risk” to human health from fires that spew smoke from burned computers and refrigerators, among others.

Given the variety of materials burned in the fires, Minos Kritikos, Senior Research Scientist and a member of the group in the collaborative labs of Clouston and Professor Benjamin Luft, suspects that a heterogeneity of particles were in the air.

People in Los Angeles who are inhaling these particles can have them “linger in their circulation for years,” said Kritikos. “It’s not just a neurological issue” as the body tries to deal with carrying around this “noxious” particulate matter. Since most neurons don’t regenerate, any toxicity induced neuronal death is irreversible, making damage to the brain permanent.

Even in non-emergency situations, people in polluted cities face increased health risks.

“There is a recognition that air pollution is a major preventable cause of Alzheimer’s Disease and related dementias, as noted by the latest Lancet Commission,” Clouston explained.

Two likely entry points

People who breathe in air containing toxic chemicals have two likely pathways through which the particulates enter the body. They can come in through the nose and, potentially, travel directly into the brain, or they can enter the lungs, circulate through the body and enter the head through the blood-brain barrier. The olfactory route is more direct, said Kritikos.

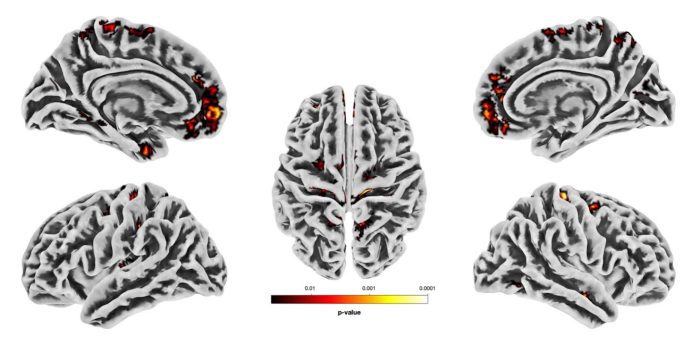

The amyloid plaques in these first responders was found primarily in the area near the nose, which supports the idea that maybe inhaling the dust was the problem, Clouston said.

Once these chemicals enter the brain, Clouston and his team believe the body engages defenses that are designed much more for viruses than for toxic compounds. The immune system can encapsulate these chemicals in amyloid plaques.

Amyloid plaques, in moderation and under conditions that protect the brain against pathogens, are a part of a protective and helpful immune response. Too much of a good thing, however, can overwhelm the brain.

“When there’s too much plaque, it can physically disturb neuronal functions and connections,” said Kritikos. “By being a big presence, they can also molecularly and chemically react with its environment.”

A large presence of amyloid can be toxically necrotic to surrounding neural tissue, Kritikos added.

What the scientists believe they are tracking is the footprint of an adaptive response that may not help the brain, Clouston added.

Clouston cautioned that the plaques and cognitive decline could both be caused by something else that scientists haven’t yet seen.

The findings

The research, which used positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans to search for evidence of amyloid plaques, found evidence that doesn’t look like old age Alzheimer’s, explained Clouston. Usually these levels of plaques are not located in one spot, but occur throughout the brain during Alzheimer’s.

The immune response may be causing some of these plaques.

The amount of amyloid plaque doesn’t look like Alzheimer’s Disease and does not appear abnormal in the traditional way of testing, but with careful analysis of the olfactory system, the researchers can find elevated levels.

“I was surprised by how little amyloid was necessary to show this association,” said Clouston.

Researchers at Mt. Sinai have examined the effect of exposure to these same particulates in mice.

“The answer is very much similar to what we see in humans,” said Clouston. “That supports this work.”

To be sure, Clouston and Kritikos are hoping to build on this research. They are particularly interested in following up with participants to measure the rate of change in these plaques from the observed amyloid signals they measured at baseline.

“Doing so would enable us to calculate the rate of amyloid buildup allowing us to assess our responders more precisely, opening doors to possible therapeutic interventions such as the recently approved anti-amyloid therapies,” Kritikos explained.

Additionally, they hope to expand on the study beyond the 35 people who participated.

It is unclear whether tamping down the immune system could make patients better or worse. By reducing amyloid plaques, scientists might enable the harmful dust to cause damage in other areas of the brain. Alternatively, however, a lower level immune response with fewer plaques might, in the longer term, be better for the brain.

This study “does open the door for some of those questions,” Clouston said. Kritikos and Clouston plan to study the presence of tau proteins and any signs of neurodegeneration in the brains of these first responders.

“More research needs to be done,” Clouston said, which specifically targets different ways of measuring exposure, such as through a biomarker. He’s hoping such a biomarker might be found that tracks levels of exposure.

Future research could also address whether post traumatic stress disorder affects the immune response.

“It’s certainly possible that PTSD is playing a role, but we’re not sure what that might be,” said Clouston.

The researchers are continuing this research as they study the effects of exposure on tau proteins and neurodegeneration.

“We are hopeful that this will be an important turning point for us,” Clouston explained

From the Medditerranean to the Atlantic

Born and raised in Cyprus, Kritikos comes from a large family who are passionate about spending time with each other while eating good food.

He earned his doctorate from the University of Bristol in England.

Kritikos met his wife Jennifer LoPresti Kritikos, who is originally from Shirley, New York, at a coffee shop in Aberdeen, Scotland, where he was doing postdoctoral research.

LoPresti, who works at Stony Brook as the Department Head Administrator for Biomedical Engineering, and Kritikos live in Manorville and have an eight year-old daughter Gia and one-year old son Theseus.

As for his work, Kritikos is grateful for the opportunity to contribute to research with Clouston and Luft, who is the Director of the Stony Brook WTC Health and Wellness Program.

“I’m happy to be in a position whereby our large WTC team (the size of a small village) is constantly pushing forward with our understanding for how these exposures have affected” the brain health of WTC first responders, Kritikos explained. He would like to continue to uncover mechanisms that underly these phenomena, not just for WTC responders but also for similarly exposed populations.

He’s heard numerous stories from a day in which the comfortable, clear air provided an incongruous backdrop for the mass murders. He has heard about people who were blown out of the buiding amid a combustible blast and about how difficult it is to put out a cesium fire.

He’s heard numerous stories from a day in which the comfortable, clear air provided an incongruous backdrop for the mass murders. He has heard about people who were blown out of the buiding amid a combustible blast and about how difficult it is to put out a cesium fire.