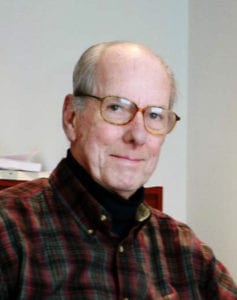

Reviewed by Elizabeth Kahn Kaplan

“Roland Palmedo: A Life of Adventure and Enterprise” looks behind the extraordinary achievements of a 20th-century pioneer in the development of skiing in this country.

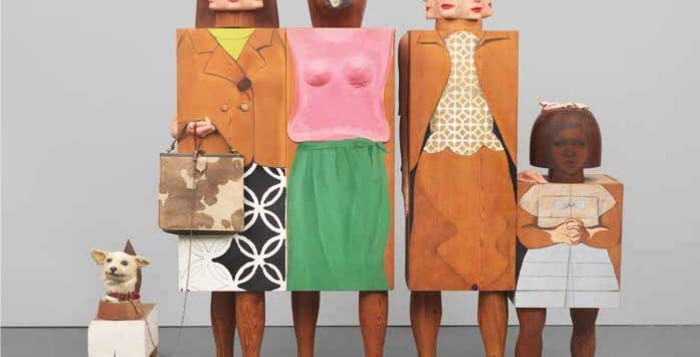

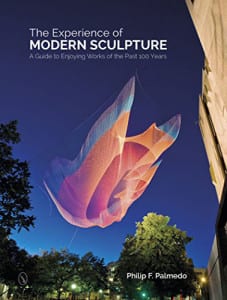

Several previous books by the author, St. James resident Philip F. Palmedo, delved into the relationship between sculptors’ lives and their work. Turning now to a subject closer to his heart, in this biography Philip explores and illuminates the traits that propelled his father to be “an exemplar of an uncommon adventurous life that has become all too rare.”

Written 40 years after Roland’s death, Philip provides more than details about his father’s adventures and accomplishments.

He reveals his father’s deeply held values and the philosophy that propelled him to create lasting institutions of benefit to many.

Born April 5, 1895, in Brooklyn, Roland was encouraged by his mother to explore Europe after high school. Visiting cousins in the German Alpines, he experienced a life in forests and mountains for the first time. Love of nature underpinned much of what he did afterward and formed a fundamental part of his character. He fell in love with skiing. Upon his return, he chose Williams College in the Berkshires, which had a ski team. He founded the Outing Club to share his love of sports with fellow student enthusiasts. This was a pattern he would follow; organizing clubs as the best way for an amateur to engage in his sport with others.

Roland was an advocate of amateurism, with separate races for amateurs and professionals in domestic and international competitions. He believed that the structure of amateur sport should give maximum encouragement to participation. College students, business people, doctors and other professionals ought to be able to enter state and national championships. A participant sport offers a great public benefit, rather than an entertainment for spectators. All the sports he loved — skiing, bicycling, kayak racing, mountain climbing — he looked upon as character building.

In the 1920s New England had no plowed roads and few accommodations in winter. Roland led friends from New York City on skiing expeditions to snowy trails and logging roads in the Berkshires and Vermont. Recreational skiing was little known.

Arguing that it could best be encouraged in clubs, he formed the Amateur Ski Club of New York in 1931. Its members supported Roland in organizing and sponsoring the first U.S. Women’s Ski Team at the 1936 Winter Olympics. The club was behind him in developing two ski areas in Vermont — Stowe during the 1930s, on Mount Mansfield, Vermont’s highest mountain; and Mad River Glen in the late 1940s. Roland initiated the Mount Mansfield Ski Lift Company at Stowe to build and operate a single-chair lift that served skiers for half a century after its opening in 1940.

Stowe became the number one ski resort in the East. When the crowds and hotels and night clubs followed, Roland sought virgin terrain in the Mad River Valley of the Green Mountains. With others he created Mad River Glen. He led a trail design team designing interesting, narrow trails that guided a skier to “experience nature’s particularities.” The nature-respecting trails were the reason for Mad River’s reputation as an expert’s mountain; bumper stickers declared, “Ski It If You Can.” Roland was determined to retain the love and joy of the sport. At his insistence, Mad River Glen was designed to keep all but serious skiers away: “No hotels; just a few homey inns; no nightlife, except of the most home-spun country sort.” It is still a favorite of amateur skiers attracted by the untouched nature of the area.

Without his financial expertise, neither Stowe nor Mad River Glen would have come to be. Similarly, he used his business organizational skills at Lehman Brothers in the 1920s to create aviation companies. Roland served on several aviation company boards, including Pan Am. He remained with Lehman Brothers until the 1960s.

The U.S. Naval Air Force was in its infancy when Roland became a member of the first air squadron, in 1917. He flew air patrols with the RAF. Returning to civilian life, he continued flying out of the now-defunct Long Island Aviation Country Club in Hicksville. He compared flying with skiing, for in both you interacted directly with and controlled the forces of nature. He flew open-cockpit planes, including a Stearman biplane, from Manchester, Vermont, to New York in 1939. Four months after Pearl Harbor, he re-enlisted in the U.S. Naval Airforce. Lt. Commander Roland Palmedo served on the aircraft carrier Yorktown near the coast of Japan.

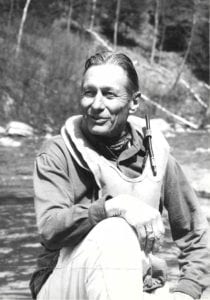

Many sons and daughters of men with distinguished careers and all-consuming personal passions have felt the loss of a warm companion and a strong guiding hand. Not so with Roland Palmedo. He taught his sons to ski and play tennis and provided adventures from white-water kayaking trips to expeditions to Europe and to Chile.

Philip appreciated Roland as a patient and loving grandfather. Roland’s granddaughter, Philip’s niece Bethlin “Scout” Proft, lives in the mountainside house that Roland rebuilt in the 1930s as “the first ski chalet in Vermont.” She created and runs a working farm there, in East Dorset. Scout quotes her granddad when she says, “Leave the world a better place.”

Roland died just before his 82 birthday on March 15, 1977. Philip regrets that he did not ask his father what it was like to fly rickety biplanes, to explore Mount Mansfield before there were lifts and to create aviation companies in the 1920s.

Perhaps those of us still lucky to have a father with whom we can celebrate this coming Father’s Day may wish to ask a few important, revealing questions. Both of you will profit.

“Roland Palmedo: A Life of Adventure and Entreprise,” Peter E. Randall Publisher, is available online at Amazon.com or from its distributor at www.enfielddistribution.com. For more information on the author, visit his website at www.philippalmedo.com.