By John L. Turner

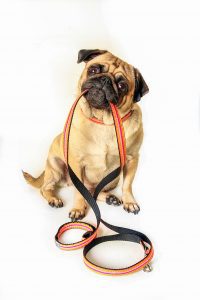

Spending time amidst the splendor of nature with family and friends at various local parks is a great way to spend a day, especially with the cooler weather of autumn. And because many parks situated throughout Long Island allow dogs, including several specifically established for dogs, you don’t have to leave your four-legged friend at home, eyeing you longingly through the screen door as you head to your car. Grab the leash and bring Fido along — you’ll both benefit from the exercise.

You already know the benefits to your health from regular exercise — weight control, cardiovascular fitness, strengthening bones and muscles, and boosting your immune system. Well, the same holds true for your dog — regular walking provides a suite of physical health benefits, an important fact considering that 50% of the dogs in America are overweight, according to a national veterinary group. Walking also provides emotional and mental health benefits to your dog — in fact, there is nothing your dog would rather do (except eating) than join their best buddy on a walk!

You already know the benefits to your health from regular exercise — weight control, cardiovascular fitness, strengthening bones and muscles, and boosting your immune system. Well, the same holds true for your dog — regular walking provides a suite of physical health benefits, an important fact considering that 50% of the dogs in America are overweight, according to a national veterinary group. Walking also provides emotional and mental health benefits to your dog — in fact, there is nothing your dog would rather do (except eating) than join their best buddy on a walk!

Dog friendly parks can be conveniently broken into two categories depending on your and your pet’s desired experience and interest: Leashed dog parks — those allowing dogs but require them to be leashed, typically larger parks open for other uses such as Blydenburgh County Park, and fenced-in dog parks — parks created exclusively for dogs where they can run and play off-leash and unrestrained within a fenced-in area with other dogs.

Given all these parks where dogs can roam and romp, there are plenty of places to explore and enjoy the outdoors with your fur-covered friend. Enjoy the time with your pet but don’t forget the leash, poop bags, water and, of course, some dog cookies.

Leashed Dog Parks

Leashed dogs are permitted in a number of state, county, and town-owned parks as well as several privately-owned parks. Here are some really special ones you and your dog are sure to enjoy.

Arthur Kunz County Park

Landing Avenue, Smithtown

631-854-4949

This is an undeveloped county park on the west side of the Nissequogue River, named in honor of a past Suffolk County Planning Director. The park offers numerous sweeping views of the Nissequogue River. Heavily forested with a few small streams that run through it to the river, it contains an abundance of tulip trees, a straight and tall tree that can grow to majestic proportions. Access is from a small parking area along the road where Landing Avenue performs a sharp turn to the right approximately 1,500 feet from its intersection with St. Johnland Road. Instead of making the sharp right, stay straight and you’ll see a small wooden sign on your left identifying the park.

Avalon Park & Preserve

200 Harbor Road, Stony Brook

631-689-0619

Privately run, this well-attended preserve straddles Shep Jones Lane. Popular features include a labyrinth and the Cartas Al Cielo (Letters to God) stainless ball sculpture by artist Alicia Framis. Ecologically it is quite diverse with numerous fields, well developed forests of beech, hickory, oak, and black birch, and frontage on Stony Brook Mill Pond, where you can see the nests of Double-crested Cormorants adorning the trees. A series of hiking trails meander through both the eastern and western sections of the preserve, rising and falling as the paths traverse the rolling terrain. Parking is either along Harbor Road near the Stony Brook Grist Mill or in the parking lots along Shep Jones Lane. Please note the park is closed on Mondays.

Blydenburgh County Park

Veterans Memorial Highway, Smithtown

631-854-3712

This large county park surrounds and includes Stump Pond (also known as Blydenburgh Lake). If you are adventurous, you can walk around the pond and in so doing will pass through some beautiful extensive forests and low lying swampy areas. The Blydenburgh National Historic District, encompassing eight structures, including a grist mill, is situated in the northwestern section of the park. It also has a fenced-in dog park. The northern entrance can be accessed from New Mill Road which intersects with Brooksite Drive. The southern access point is through an entrance road from State Route 347 across from the Hauppauge County Center.

Chandler Estate Park

233 N. Country Road, Mt. Sinai

631-854-4949

This 40-acre Suffolk County-owned preserve is situated on the southern edge of Mount Sinai Harbor. The park is laced with trails but given its small size you can’t really get lost. Pass through a metal gate and within a short distance will have the choice to at a fork in the trail. If you stay straight it will take you more quickly to the edge of the harbor. The trail to the right leads east and a smaller trail to your left will take you north toward the harbor too. This park is a small gem that is definitely worth getting to know better. Access to the park is gained through the parking lot of the Mt. Sinai Congregational Church situated near the corner of the cemetery.

Cordwood Landing County Park

Landing Avenue, Miller Place

631-854-4949

This 70-acre nature preserve located in Miller Place was formerly Camp Barstow, a Girl Scout camp. It was named to reflect the cordwood industry which was an important economic driver in the mid-to-late nineteenth century in Suffolk County. The main path leads to the more than 1000 feet of beach front. If you want a more circuitous walk through this heavily forested preserve dominated by oaks, hickories, birch and beech, there is a trail that meanders through the preserve’s eastern portion before following the top of the bluff that fronts on Long Island Sound. This section of the trail provides breathtaking views of the Sound and shoreline.

Forsythe Meadow County Park

52 Hollow Road, Stony Brook

631-854-4949

A 34-acre preserve that sits above the Stony Brook Village Center, the County’s Forsythe Meadow/Nora Bredes Preserve has a 1.2 mile circular trail that loops through the meadows and woodlands of the preserve. The diversity of habitats makes it a good place to see birds, butterflies, deer and other wildlife. A few breaks in the forest canopy provide views of Stony Brook Harbor in the winter. Access is via a stone lined road, next to the county park sign, off of Hollow Road.

Frank Melville Memorial Park

1 Old Field Road, Setauket

631-689-6146

The “Central Park” of Setauket, the privately-run 24-acre park was dedicated in 1937 to the memory of Frank Melville Jr., father of local philanthropist Ward Melville. This community treasure consists of forested land adjacent to the southern end of Conscience Bay. The scenic pond, bracketed by two stone bridges, is the central attraction of the park and countless visitors like to walk around the pond on the paved trail that circles it. A simulated grist mill is adjacent to the northern bridge and the vantage point from this bridge offers a panoramic view of the Bay. This park is easily reached either by accessing Bates Road off of Main Street near the village green in Setauket, or park in one of the designated parking spaces on Main Street adjacent to the Setauket Post Office.

Heckscher Park

2 Prime Ave., Huntington

631-351-3089

Heckscher Park, the Town of Huntington’s “Central Park”, of which it appears to represent a small-scale version, is pretty! A small lake, situated in the northwestern portion of the park, provides habitat for turtles and a variety of waterbirds including ducks, swans and geese. A number of paved trails, including one around the lake, are laid out through the park. When tired, you and your pet can rest in the large grassy sections and enjoy manicured gardens. Parking is provided along the south side of Madison Avenue.

Makamah Nature Preserve

Fort Salonga Road, Fort Salonga

631- 854-4949

Another undeveloped, yet beautiful, preserve laced with hiking trails, Makamah Nature Preserve is part of the Crab Meadow watershed and, adjoining the Town of Huntington-owned Crab Meadow Golf Course and marshland area, forms more than 500 acres of contiguous preserved open space. The property, which was acquired by Suffolk County in 1973, is heavily forested, dominated by oaks, several hickory species, black birch,with spicebush growing in the understory. IThe main loop trail that runs around the edge of the preserve (there are quite a few interior trails that can complicate your walk so it’s best to bring a trail map) provides great views of the stream valley to the east which flows into the marsh and at one vantage point offers a panoramic view of the Crab Meadow Marsh. Access to the property is from a parking lot that fronts on State Route 25A, a little bit west of its intersection with Makamah Road.

Port Jefferson Public Beach

East Broadway, Port Jefferson

631-473-4724

Located on the west side of Port Jefferson Harbor, this well-known dog park and beach is a great place for your pet to get some exercise while providing pretty views of the harbor for the enjoyment of the dog’s two-legged companions. It is a bit tricky to get to. It is located north of the main section of Harborfront Park, so drive in the main access road to the park, driving past the Village Center and Bayles Boat Shop and, finally, past the numerous parking spaces on your right. When you reach a fork bear left and go straight and you’ll see the elongated parking lot for the beach.

Setauket-Port Jefferson Station Greenway Trail

631-689-0225

This 5.1 mile long Setauket to Port Jefferson Station Greenway trail provides a scenic path connecting these two communities together. Along the way, on this slightly undulating paved path, you’ll pass by occasional open areas and fields, as well as dense forests dominated by various oak, hickory and other trees. The trail crosses over numerous roads including Gnarled Hollow Road, Old Town Road, and Sheep Pasture Road, and along your journey you can contemplate how and why they got their names. Access to the Greenway is available from both its ends. The western terminus is accessed through the parking lot situated on Limroy Lane, off of Route 25A while the eastern end at Clifton Place is gained through the elongated parking lot on the west side of State Route 112 across from its intersection with Hallock Lane.

Thomas Muratore Park at Farmingville Hills

501 Horseblock Road, Farmingville

631-854-4949

This heavily wooded undeveloped 105-acre park was purchased by the county in the 1980s as a part of the Open Space Preservation Act. The 105-acre park officially opened to the public in May of 2010 and was renamed in memory of Leg. Tom Muratore in April of this year. Approximately 1.2 miles of hiking trails, consisting of two loops, weave among the forest that is rolling in nature, containing elevations that reach as high as 270 feet above sea level. Two historic structures managed by the Farmingville Historical Society — the 1850 Greek Revival School House and the Terry House, built in 1823 — are found in the southeastern section of the park. There is parking for about a dozen vehicles.

West Hills County Park

181 Sweet Hollow Road, Huntington

631-854-4423

This is a large park situated on the highest section of the Ronkonkoma Moraine, the row of hills formed by the third of four glaciers that advanced during the Ice Age which shaped and created Long Island. In fact, Jayne’s Hill, the highest point on Long Island, topping out at the nose-bleed elevation of 401 feet (actually the height has never been precisely determined with heights as low as 383 feet and high as 414 feet being stated), is situated in the northeastern corner of the park. On top there is a boulder containing a plaque in which Walt Whitman’s well-known piece “Paumanok” is inscribed, a poem which in such a distilled way captures the essence of Long Island. The Walt Whitman Trail, a loop which connects Whitman’s birthplace with the county park and Jayne’s Hill, is about 3.6 miles long — a nice hike for a morning or afternoon. Jayne’s Hill is reached off of Reservoir Road while additional access is off of Sweet Hollow Road and High Hold Drive.

Fenced-in Parks

There are several smaller, fenced-in parks where your dog can romp off-leash, socializing and playing with other dogs. The Town of Brookhaven, for example, has established several dog parks, the two closest fenced-in parks being the Middle Island Dog Park, 1075 Middle Country Road, Middle Island and the Selden Dog Park, 100 Boyle Road, Selden. A Pooch Pass from the town is required. Likewise, the Town of Smithtown has a fenced-in dog park at Charles P. Toner Park, 148 Smithtown Blvd. in Nesconset.

Suffolk County maintains several established, fenced-in dog parks too, situated within larger county parks located in the northern half of Suffolk County. Two popular ones are the dog parks at West Hills and Blydenburgh County Parks

A resident of Setauket, author John Turner is conservation chair of the Four Harbors Audubon Society, author of “Exploring the Other Island: A Seasonal Nature Guide to Long Island,” president of Alula Birding & Natural History Tours and pens a monthly column for TBR News Media titled Nature Matters.

This article originally appeared in TBR News Media’s 2022 Harvest Times supplement.

You already know the benefits to your health from regular exercise — weight control, cardiovascular fitness, strengthening bones and muscles, and boosting your immune system. Well, the same holds true for your dog — regular walking provides a suite of physical health benefits, an important fact considering that 50% of the dogs in America are overweight, according to a national veterinary group.

You already know the benefits to your health from regular exercise — weight control, cardiovascular fitness, strengthening bones and muscles, and boosting your immune system. Well, the same holds true for your dog — regular walking provides a suite of physical health benefits, an important fact considering that 50% of the dogs in America are overweight, according to a national veterinary group.