By Daniel Dunaief

Before treatments for any kind of health problem or disease receive approval, they go through a lengthy, multi-step process. This system should keep any drugs that might cause damage, have side effects or be less effective than hoped from reaching consumers.

In the world of cancer care, where patients and their families eagerly await solutions that extend the quality and quantity of life, these clinical trials don’t always include the range of patients who might receive treatments.

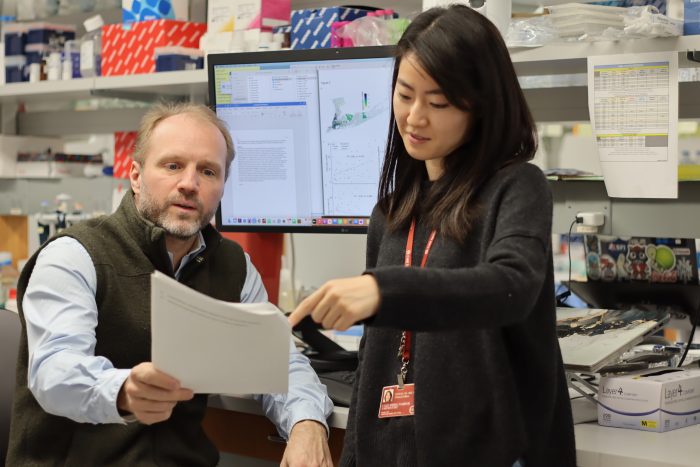

That’s according to a recent big-picture analysis in the lab of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Professor Tobias Janowitz. Led by clinical fellow Hassal Lee, these researchers compared where clinical trials occurred with the population near those centers.

Indeed, 94 percent of United States cancer trials involve 78 major trial centers, which were, on average, in socioeconomically more affluent areas with higher proportions of self-identified white populations compared with the national average.

“We should test drugs on a similar population on which we will be using the drugs,” said Lee. In addition to benefiting under represented groups of patients who might react differently to treatments, broadening the population engaged in clinical trials could offer key insights into cancer. Patient groups that respond more or less favorably to treatment could offer clues about the molecular biological pathways that facilitate or inhibit cancer.

Janowitz suggested that including a wider range of patients in trials could also help establish trust and a rapport among people who might otherwise feel had been excluded.

The research, which Lee, Janowitz and collaborators published recently as a brief in the journal JAMA Oncology, involved using census data to determine the socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds of patient populations within one, two and three hour driving distances to clinical trials.

The scientists suggested researchers and drug companies could broaden the patient population in clinical trials by working with cancer centers to enlist trial participants in potential life-extending treatments through satellite hospitals.

Project origins

This analysis grew out of a study Janowitz conducted during the pandemic to test the effectiveness of the gerd-reducing over-the-counter drug famotidine on symptoms of Covid-19.

Janowitz generally studies the whole body’s reaction to disease, with a focus on cancer associated cachexia, where patients lose considerable weight and muscle mass. During the pandemic, however, Janowitz, who has an MD and PhD, used his scientific skills to understand a life-threatening disease. He designed a remote clinical trial study in which participants took famotidine and monitored their symptoms.

While the results suggested that the antacid shortened the severity and duration of symptoms for some people, it also offered a window into the way a remote study increased the diversity of participants. About 1/3 of the patients in that population were African American, while about 1/4 were Hispanic.

Lee joined Janowitz’s lab in early 2022, towards the end of the famotidine study.

“The diverse patient population in the remote trial made us wonder if commuting and access by travel were important factors that could be quantified and investigated more closely,” Janowitz explained.

Lee and Janowitz zoomed out to check the general picture for cancer clinical trials.

To be sure, the analysis has limitations. For starters, the threshold values for travel time and diversity are proof of concept examples, the scientists explained in their paper. Satellite sites and weighted enrollment also were not included in their analysis. The cost other than time investment for potential clinical trial participants could present a barrier that the researchers didn’t quantify or simulate.

Nonetheless, the analysis suggests clinical trials for cancer care currently occur in locations that aren’t representative of the broader population.

The work “leveraged freely available data and it was [Lee’s] effort and dedication, supported by excellent collaborators that we had, that made the study possible,” Janowitz explained.

Since the paper was published, Cancer Center directors and epidemiologists have reached out to the CSHL scientists.

Searching for clinical research

After Lee, who was born in Seoul, South Korea and moved to London when she was five, completed her MD and PhD at the University of Cambridge, she wanted to apply the skills she’d learned to a real-world research questions.

She found what she was looking for in Janowitz’s lab, where she not only considered the bigger picture question of clinical trial participation, but also learned about coding, which is particularly helpful when analyzing large amounts of data.

Lee was particularly grateful for the help she received from Alexander Bates, who, while conducting his own research in a neighboring lab in the department of Neurobiology at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, offered coding coaching.

Lee described Bates as a “program whiz kid.”

A musician who enjoys playing classical and jazz on the piano, Lee regularly listened to music while she was in the lab. Those hours added up, with Spotify sending her an email indicating she was one of the top listeners in the United Kingdom. The music service invited her to an interview at their office to answer questions about the app, which she declined because she had moved to the United States by then.

The top medical student at Cambridge for three years, Lee said she enhanced her study habits when she felt unsure of herself as a college student.

She credits having great mentors and supportive friends for her dedication to work.

Lee found pharmacology one of the more challenging subjects in medical school, in part because of the need to remember a large number of drugs and how they work.

She organized her study habits, dividing the total number of drugs she needed to learn by the number of days, which helped her focus on studying a more manageable number each day.

Lee will be a resident at Mt. Sinai Hospital later this year and is eager to continue her American and New York journey.

As for the work she did with Janowitz, she hopes it “really helps people think about maintaining diversity in clinical trials using data that’s already available.”