By Daniel Dunaief

Health care providers can use all the help they can get amid an ongoing opioid epidemic that claims the lives of 130 Americans each day.

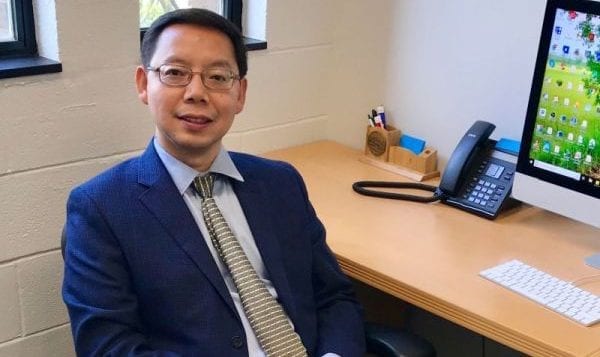

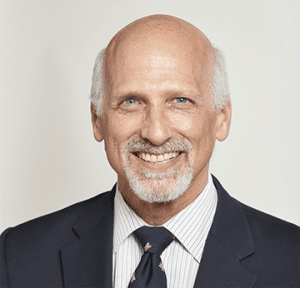

In a cross-disciplinary effort that combines the computer science skills of Fusheng Wang and the clinical knowledge and experience of doctors including Dr. Richard Rosenthal, Stony Brook University is developing an artificial intelligence model that the collaborators hope will predict risk related to opioid use disorder and opioid overdose.

Wang, a Professor in the Department of Biomedical Informatics and Computer Science at Stony Brook and Rosenthal, a Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health in the Renaissance School of Medicine, received a $1.05 million, three-year contract from the independent funding organization Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI).

“We have patients, clinical stakeholders, clinician scientists and community-based people within the system of care that have an interest at the table in the development cycle of this AI mechanism from day one,” Rosenthal said. The PCORI required that the scientists identify these stakeholders as a part of the research strategy.

The Stony Brook researchers are combining data from Cerner, a major electronic health record vendor under an institutional data usage agreement, with an awareness of the need to create a program that doctors can use and patients can understand.

Traditional public health studies rely on analyzing incidents that occurred. This approach, however, can be applied to population health management through early interventions, Wang explained.

With artificial intelligence, computer scientists typically plug enormous amounts of data into a model that searches through individual or combined factors and comes up with a prediction through a deep learning process.

The factors, which may be in the hundreds or even more, that contributed to the conclusion about a risk level aren’t always clear, which makes them difficult for doctors to explain and for patients to understand. Many of the factors may not be clinically intuitive.

Deep learning models can provide certain types of information about the prediction, such as a ranking of top factors. These factors, however, may not necessarily be clinically relevant, Wang explained.

To balance the need for data-driven analysis with the desire to create a product that people feel confident using, the scientists plan to become a part of the process.

“We are all going to educate each other,” said Rosenthal. “Patients will tell you what it means to be a patient, to be at the receiving end of some doctors telling them something they don’t know” while each group will share their lived experience.

Each participant will be a student and a teacher. Rosenthal believes this stakeholder in the loop approach will create a tool that is clinically relevant.

“There’s an opportunity to produce a highly accurate predictive mechanism that is highly acceptable based on transparency,” he said.

To be sure, people involved in this process could deemphasize a factor that doesn’t make sense to them, but that might otherwise increase the predictive accuracy of the developing model.

“This might come at the expense of the performance metric,” Rosenthal said.

Still, he doesn’t think any human correction or rebalancing of various factors will reduce the value of the program. At the same time, he believes the process will likely increase the chances that doctors and patients will react to its prognosis.

A program with a personal touch

Wang created the model the scientists are using and enhancing. He reached out to several physicians, including Director of the Primary Care Track in Internal Medicine Rachel Wong and later, Rosenthal, for his addiction research expertise.

Rosenthal started collaborating on grant proposals focused on big data and the opioid epidemic and attending Wang’s graduate student workgroup in 2018.

Wang recognized the value of the clinician’s experience when communicating about these tools.

“Studies show that patients have lots of skepticism about AI,” he explained. Designing a tool that will generate enough information and evidence that a patient can easily use is critical.

The kind of predictions and risk profiles these models forecast could help doctors as they seek the best way to prevent the development of an addiction that could destroy the quality and quantity of their patients’ lives.

“If we can identify early risk before the patient begins to get addicted, that will be extremely helpful,” Wang added.

If opioid use disorder has already started for a patient, the tool also could predict whether a patient has a high chance of ending treatment, which could create worse outcomes.

Refinements to the model will likely include local factors that residents might experience in one area that would be different for populations living in other regions.

Depending on what they learn, this could allow “us to frame our machine learning questions in a more context-dependent population, population-dependent domain,” Rosenthal said.

Opioid-related health problems in the northeast, in places like Long Island, is often tied to the use of cocaine. In the Southwest, the threat from opioids comes from mixing it with stimulants such as methamphetamines, Rosenthal added.

“Localization increases the accuracy and precision” in these models, he said.

Eventually, the model could include a risk dashboard that indicates what kind of preventive measures someone might need to take to protect themselves.

The scientists envision doctors and patients examining the dashboard together. A doctor can explain, using the model and the variable that it includes, how he or she is concerned about a patient, without declaring that the person will have a problem.

“Given these factors, that puts you at greater risk,” said Rosenthal. “We are not saying you’re going to have a problem” but that the potential for an opioid-related health crisis has increased.

Unless someone already has a certain diagnosis, doctors can only discuss probabilities and give sensible recommendations, Rosenthal explained.

They hope the tool they are developing will offer guidance through an understandable process.

“At the end of the day, the machine is never going to make the decision,” said Rosenthal. With the help of the patient, the clinician can and should develop a plan that protects the health of the patient.

“We’re aiming to improve the quality of care for patients,” he said.