By Daniel Dunaief

Don’t say “no” to Florence Aghomo.

A graduate student at Stony Brook University who was born and raised in Cameroon, Aghomo’s ability to get past no, don’t, and shouldn’t led to a continent-hoping life complete with a recent compelling discovery in the rainforest of Madagascar.

Working on her PhD research in the laboratory of Distinguished Professor Patricia Wright, Aghomo went north in Ranomafana National Park when almost every other researcher has gone south in the national park. She was searching for a type of lemur called the Milne-Edwards’s Sifaka when she came upon a large hole on a steep surface.

She suggested to her guide that it was a cave. Her guide insisted she was wrong. When she spoke with Wright, her advisor also was unconvinced.

Aghomo, however, was sure that what she saw was similar to the caves she studied in the class of Adjunct Lecturer Dominic Stratford, who has a dual position at Wits University in South Africa.

In November, several months after Aghomo’s initial discovery, a team of scientists trekked into the remote part of the rainforest in the north.

“It’s very, very difficult terrain,” Wright said.

The group found 13 caves, one of which, to their amazement, contained fossilized bones.

“This is impossible,” Wright recalled thinking. “Bones don’t fossilize in the rainforest. Everyone knows that.”

But, as the evidence suggested, they can and they do.

The researchers initially thought the unexpected bones were a pig.

“I’m saying, ‘No, it’s not a wild pig,’” said Wright. “That is a hippopotamus. They couldn’t believe it.”

Indeed, while three species of pygmy hippopotami have been discovered in parts of the island nation off the southeast coast of the African continent, none have been discovered in the rainforest.

Once the group at Centre ValBio, the research station in Ranomofana National Park run by Wright, confirmed the discovery, Wright immediately took two actions.

First, she wrote to Stratford.

“This is what we found and it is your fault for teaching Florence how to look for a cave,” Wright said. “It’s your responsibility to come over and help us. I’m not a paleontologist and you are.”

Stratford described the first few weeks after the discovery as frantic, as he had to grade papers, apply for a visa and make complicated travel plans – all before any possible rain washed away this remarkable discovery.

Stratford was thrilled with the finding.

“It was great to know that something you teach at Stony Brook University in the middle of the Northeast has helped somebody make a discovery on the other side of the planet in a rainforest,” said Stratford. The discovery “couldn’t be further away from where we are right now, sitting here in the snow.”

She Wright also wrote to the Leakey Foundation to secure emergency funds to bring experts to the area quickly before the rainy season threatened to wash away this remarkable find.

“This was a really great opportunity to use these emergency funds and is exactly the kinds of things we want to do,” said Carol Ward, co-chair of the Scientific Executive Committee for Paleoanthropology at the Leakey Foundation. “To find a cave system in this rainforest that’s preserving these fossils is really special.”

Acidic rainforest soils make the discovery of fossils in these areas rare.

Seeing the bones

Once Aghomo was able to see the fossilized bones, Wright appreciated the variety of information they these fossils might contain.

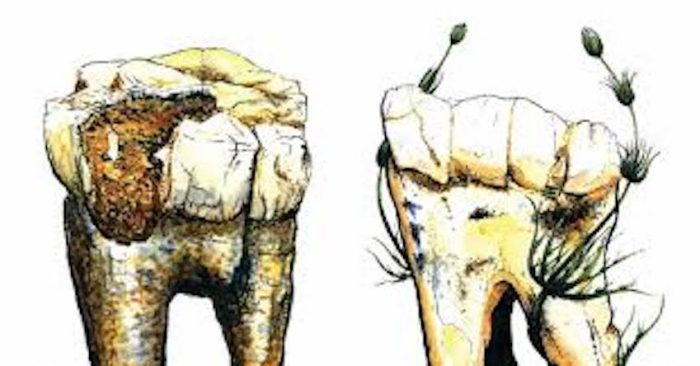

The bones had a mandible with molars that “look like flowers,” Wright said. “They had a really nice wear pattern.”

Based on the amount of wear on the teeth, Wright estimates that the individual hippo might have been a young adult when it died.

The collection of bones also included a tusk and several leg bones.

Stratford, who helped carefully excavate the bones with researchers from the University of Antananrivo (Tana), believes this pygmy hippo likely died in the cave. He is hopeful that they might find other parts of the same hippo’s skeleton that got washed into different parts of the cave.

Relatively speaking, this hippo has a smaller cranium and longer legs than similar species on the island nation. Wright suspects that the hippo is a different species from the three that have been categorized in Madagascar.

The bones are sitting in a refrigerator at CVB and Wright hopes to bring them to Stony Brook by some time around May, when Stratford and others might be able to examine them.

Researchers are hoping to answer several questions about the animal, including the age of the fossil as well as the food in its diet based on whatever they can extract from the teeth.

Searching other caves

Researchers, meanwhile, have discovered a tusk from another hippo in another nearby cave.

Wright is excited about the possibility of finding other fossilized bones in caves created by granite boulders that tumbled down a steep slope. Some of the caves have water running at the bottom of them, which can be meters down from their entrance. Scientists used ropes to descend into the caves.

Wright, who has won a range of awards from her research on these quirky lemurs and was the subject of the Morgan Freeman-narrated film “Island of Lemurs: Madagascar,” believes some of these caves may reveal a whole new set of fossil lemurs.

Wright hopes to return to Madagascar next summer to do the rest of the excavation with paleontologists.

As for Aghomo, the eagerness to blaze her own trail that led her to find these caves in an isolated area is part of a lifelong pattern in which persistence and a willingness to follow difficult paths has paid off.

When she was younger, Aghomo wanted to work in the forest. Her father, Jean-Marie Fodjou, however, suggested such difficult physical work might not be especially challenging for a woman.

Her father didn’t think she would be comfortable walking distances in difficult terrain, crossing rivers, and carrying heavy loads.

Aghomo, however, recognized that it’s “something I want to do.”

The path to Stony Brook wasn’t immediate either. The first year she applied to the graduate program, she sent her application to the wrong department.

In her second year, she was accepted in the Interdepartmental Doctoral Program in Anthropological Sciences but found it difficult to get a visa. Finally, in her third year, she was accepted and received her visa.

This past December, Aghomo won the Young Women in Conservation Biology Award from the Society for Conservation Biology, which recognizes the work of young women in Africa who advance conservation biology.

Recently, Aghomo was back home with her father, who is “so proud of me.”

While she didn’t listen to his advice about staying out of the rainforest, he is pleased that he urged her to pursue her interests to the best of her ability.

“He told me, ‘Do it as well as you can,’” said Aghomo.

Despite the challenge of trekking to parts of a Madagascar rainforest that others don’t generally visit, of following her own path into the forest and of persisting in her efforts to start a PhD program at Stony Brook, Aghomo remains committed to following her own path.

She is hopeful that the discovery of fossils in a few caves in Madagascar leads to additional searches in other rainforests.

After this finding, perhaps paleoanthropologists will “think of searching in Central African countries for fossils.”

As for Ward, she believes the fossilized bones from an extinct species might provide information about human interactions with the world and climate and environmental change that “we might learn from today. There might be lessons about what’s happening now that [we can get] buy looking at what happened in the past.”