By Daniel Dunaief

Up and coming scientists are often stuck in the same position as promising professionals in other fields. To get the funding for research they’d like to do, they need to show results, but to get results, they need funding. Joseph Heller, author of “Catch 22,” would certainly relate.

A New York-based philanthropy called the Pershing Square Sohn Cancer Research Alliance is seeking to fill that gap, providing seven New York scientists with $600,000 each over the course of three years.

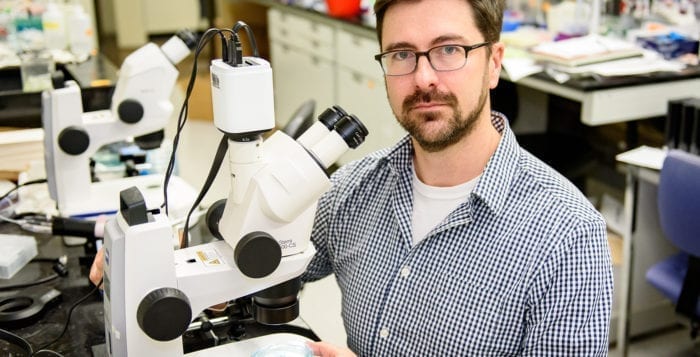

In the fifth annual competition, Benjamin Martin, an associate professor in the Department of Biochemistry & Cell Biology at Stony Brook University, won an award for his study of zebrafish models of metastatic cancer. Martin is the first Stony Brook researcher to win the prize.

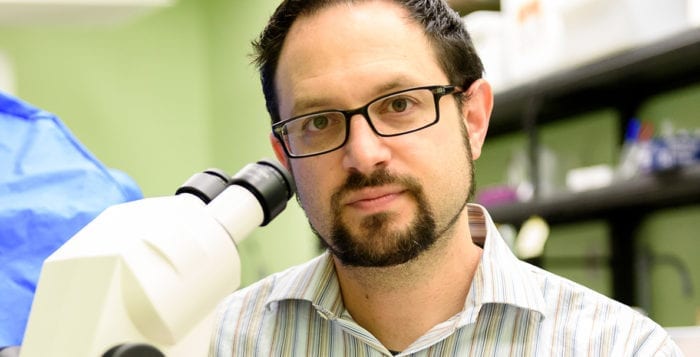

Working with Assistant Professor David Matus, whose lab is across the hall and whose research team conducts weekly group meetings with Martin’s lab, Martin is able to see in real time the way grafted human tumor cells spread through blood vessels to other organs in the transparent zebrafish.

“It’s been very challenging to understand what process cancer cells are using to metastasize and leave the blood vessels,” said Olivia Tournay Flatto, the president of the Pershing Square Foundation. “With this technology, he can see what’s happening. It’s a really powerful tool.”

The work Martin presented was “really appealing to the whole board, and everybody felt this kind of project” had the potential to bring data and insights about a process researchers hope one day to slow down or stop, said Flatto.

This year, about 60 early-stage investigators applied for an award given specifically to researchers in the New York City area. When he learned that he won, Martin said, “There was some dancing going on in the living room.” He suggested that the award is a “validation” of his research work.

The process of a cancer cell leaving a blood vessel is “basically a black box” in terms of the mechanism, Martin said. It’s one of the least understood aspects of metastasis, he added.

Indeed, a developmental biologist by training, Martin is hoping to discover basics about this cancer-spreading process, such as an understanding of how long it takes for cancer cells to leave blood vessels. The process can take hours, although it’s unclear whether what he’s seen is typical or abnormal.

Martin would like to identify how the cancer cells adhere to the blood vessel walls and how and why they leave once they’ve reached their target.

Metastatic cancer is likely using the same mechanism the immune system uses to travel to the sites of infection, although researchers still need to confirm several aspects of this model.

Moving in involves interactions with white blood cells, including macrophages. With white blood cells, an area of infection or inflammation becomes activated, which triggers a reaction of adhesion molecules called selectins.

By watching a similar transport process in cancer, Martin and Matus can “see things people haven’t seen before” and can explore way to inhibit the process, Martin suggested.

He is hoping to find ways to stop this process, forcing cancer cells to remain in the blood vessels. While he doesn’t know the outcome of a cancer cell’s prolonged stay in the vessel, he predicts it might end up dying after a while. This approach could be combined with other therapies to force the cancer cells to die, while preventing them from spreading.

Through this grant, Martin will also study how drugs or mutations in selectins generate a loss of function in these proteins, which affects the ability of cancers to leave the blood vessel.

Martin plans to use the funds he will receive to hire more postdoctoral researchers and graduate students. He will also purchase additional imaging equipment to enhance the ability to gather information.

Martin appreciates that this kind of research, while promising, doesn’t often receive funding through traditional federal agencies. This type of work is often done on a mouse, which is, like humans, a mammal. The enormous advantage to the zebrafish, however, is that it allows researchers to observe the movement of these cancer cells, which they couldn’t do in the hair-covered rodent, which has opaque tissues.

“There’s a risk that these experiments may not work out as we planned,” Martin said. He is hopeful that the experiments will succeed, but even if they don’t, the researchers will “learn a great deal just from seeing behaviors that have not been observed before.”

Indeed, this is exactly the kind of project the Pershing Square Sohn Cancer Research Alliance seeks to fund. They want scientists to “put forward the riskiest projects,” Flatto said. “We are ready to take a chance” on them.

One of the benefits of securing the funding is that the alliance offers researchers a chance to connect with venture capitalists and commercial efforts. These projects could take 20 years or more to go from the initial concept to a product doctors or scientists could use with human patients.

“We are not necessarily focused on them starting a company,” Flatto said. “We think some of those projects will be able to be translated into something for the patient,” which could be through a diagnosis, prevention or treatment. “This platform is helpful for young investigators to be well positioned to find the right partners,” he added.

Aaron Neiman, the chairman of the Department of Biochemistry & Cell Biology at SBU, suggested that this award was beneficial to his department and the university.

“It definitely helps with the visibility of the department,” Neiman said. The approach Matus and Martin are taking is a “paradigm shift” because it involves tackling cells that aren’t dividing, while many other cancer fighting research focuses on halting cancer cells that are dividing.

Neiman praised the work Martin and Matus are doing, suggesting that “they can see things that they couldn’t see before, and that’s going to create new questions and new ideas,” and that their work creates the opportunity to “find something no one knew about before.”