The initiative, secured by Senator Schumer, will receive $10 million in federal funds

Stony Brook University will lead a new, innovative network of regional biomedical research institutions to accelerate translational research that will impact and advance clinical care for many physical and mental health conditions. Called the Long Island Network for Clinical and Translational Science (LINCATS), it will be headquartered at Stony Brook University. The initiative will be in collaboration with Brookhaven National Lab (BNL), Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, and the Northport VA Medical Center. Central to LINCATS establishment is $10 million in federal funding secured by Senator Chuck Schumer and supported by Senator Gillibrand, part of Congress’ omnibus funding bill of which Long Island will receive some $50 million.

The overall mission of LINCATS is to accelerate the public health impact of research, especially for underserved communities across Long Island, by offering access to innovative and transformative research programs and educational services. To improve the health of Long Island’s three million-plus population, the bioscience collaborative will engage in work ranging from basic research and clinical trials, to addressing vulnerable populations and disparities, and incorporating innovative research and practices such as the use of bioinformatics, artificial intelligence, telehealth, genotyping, proteomics, and engineering-driven medicine.

“I am incredibly grateful to Senator Schumer for securing such crucial funding for the establishment of the Long Island Network for Clinical and Translational Science (LINCATS) at Stony Brook University,” said Stony Brook University President Maurie McInnis. “Through LINCATS, the entire Long Island community and the greater New York region will have access to a comprehensive health research network that is capable of a rapid response to emergent healthcare risks, including a future global pandemic. New York and the nation are fortunate to have such a visionary leader as Senator Schumer, who champions the cutting-edge science research and health innovation that will provide important and much-needed economic boosts to development on Long Island.”

The initial funding will help to scale-up operations of this research and healthcare service network, creating an ecosystem that will fast-track the application of new scientific discoveries in clinical medical care, helping to provide new treatments to more patients throughout Long Island.

“With renowned institutions like BNL, Cold Spring Harbor Lab, and Stony Brook University, Long Island is a hub for world-class scientific research and groundbreaking discoveries,” said Senator Chuck Schumer. “To bolster continued success and innovation, I worked to ensure that, as part of Congress’s historic bipartisan budget agreement, $10 Million will head to Stony Brook to help create the Long Island Network for Clinical and Translation Science. This federal funding will help scale-up operations of this research and healthcare service network, creating an ecosystem that will fast-track the application of new scientific discoveries in clinical medical care. Not only will LINCATS put Long Island on the map as a center of clinical healthcare research, it will help provide innovative new treatments to benefit more patients throughout the region.“

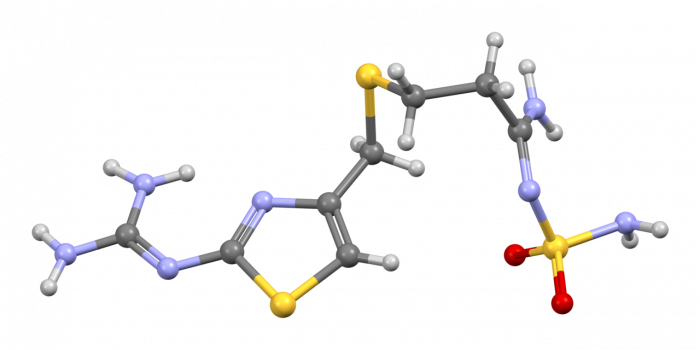

One specific aspect of the collaborative work will be researching and addressing diseases and environmental factors that are prevalent on Long Island, such as Lyme disease, emerging pathogens and environmental risks due to the impact of climate change on coastal resiliency, as well as the unique challenges related to opiate addiction.

“LINCATS is Stony Brook’s response to the National Institutes of Health’s call to action to create research hubs designed to expand and elevate the bench-to-bedside ecosystem within communities nationwide,” said Richard J. Reeder, PhD, Vice President for Research at Stony Brook University. “We are fully committed to supporting this prominent team of biomedical researchers and practitioners who are set to lead and deliver groundbreaking discoveries.”

LINCATS will also serve as a catalyst to create hundreds of new jobs in the bioscience sector, and potentially thousands of jobs when the infrastructure is fully operational. The network will provide a workforce of both scientists and clinicians from multiple institutions working in partnership with all communities across Long Island to address all health care challenges.

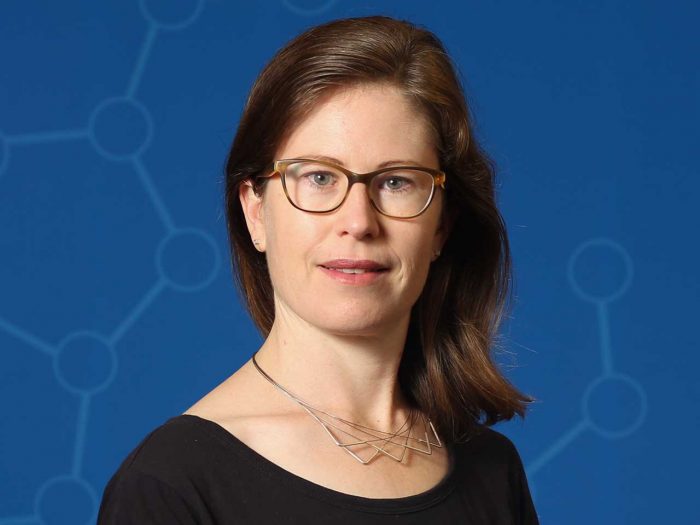

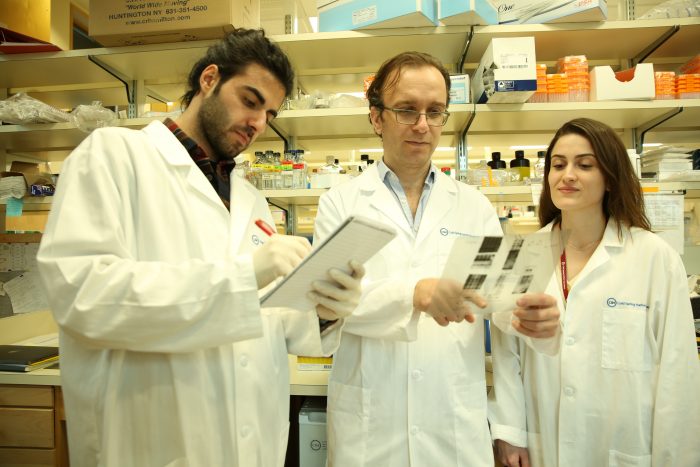

Anissa Abi-Dargham, MD, SUNY Distinguished Professor, Vice Chair for Research and the Lourie Endowed Chair in Psychiatry, will serve as the Principal Investigator and Director of LINCATS. The LINCATS leadership team at Stony Brook includes 17 members, virtually all of whom are prominent faculty scientists and medical scientists in multiple fields at the University, such as Pharmacological Sciences, Infectious Diseases, Biotechnology, and Public Health.

“I am extremely thankful for Senator Schumer’s support of LINCATS. The funds will allow us to deepen our investments in the infrastructure, training, and community engagement pillars necessary to fulfill the mission of LINCATS,” says Dr. Abi-Dargham. “I am also grateful for the team of scientists, educators and community members who worked with me to develop the large collaborative project, and for the assistance of the Office of Proposal Development under the direction of Nina Maung.”

When the program is officially in place, funds will also be used for core personnel, supplies and equipment, support for multidisciplinary research, and the construction of an inpatient research unit at Stony Brook Hospital for the purpose of translational and clinical biomedical research.