By Daniel Dunaief

Chances are high you won’t see Dr. Brendan Boyce when you visit a doctor. You will, however, benefit from his presence at Stony Brook University Hospital and on Long Island if you have bone or soft tissue lesions and you need an expert pathologist to diagnose what might be happening in your body.

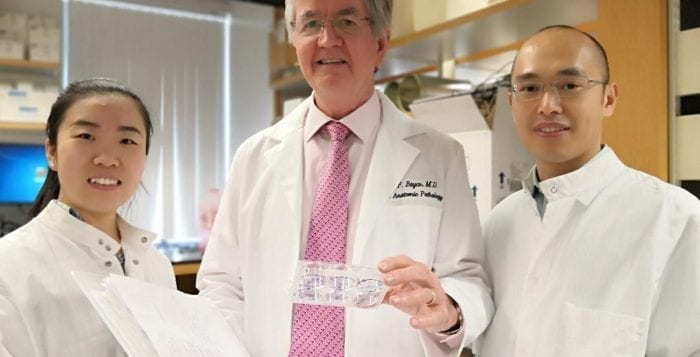

A professor at the University of Rochester for 20 years, the internationally renowned Boyce joined the Renaissance School of Medicine at SBU in November, splitting his time between Rochester and Long Island.

Dr. Ken Shroyer, the chair of the Department of Pathology, reached out to Boyce with an unusual bone tumor case last spring. After that discussion, the two considered the possibility of Boyce adding his bone and soft tissue pathology expertise to the growing department. Boyce was receptive to the idea, particularly because his daughter Jacqueline lives in Woodbury with two of his seven grandchildren.

For local patients, Boyce adds a relatively rare expertise that could shorten the time for a diagnosis and improve the ability for doctors to determine the best course of action during surgeries.

“While the patient is already undergoing a surgical procedure, the preliminary diagnosis can guide the process of the surgery,” said Shroyer. “That’s difficult to achieve if we are dependent on an outside consultant. It happens, more or less in real time, if Boyce can look at the slides as they are being prepared and while the patient is still on the operating table.”

Prior to Boyce’s arrival, Stony Brook functioned the same way most academic medical centers do around the country when it came to bone and soft tissue cancers or disorders.

“There are only a handful of soft tissue and bone surgical pathology subspecialists around the country,” Shroyer said. “There’s an insufficient number of such individuals to make it practical like this at every medical school in the country.”

Many of these cases are “rare” and most pathologists do not see enough cases to feel comfortable diagnosing them without help from an expert, Boyce explained.

Boyce “was recruited here to help this program at Stony Brook continue to grow,” Shroyer said. “He enhances the overall scope of the training we can provide to our pathology residents through his subspecialty expertise. Everything he does here is integrated with the educational mission” of the medical school.

While bone and soft tissue tumors are relatively rare compared to other common cancers, such as colorectal or breast cancer, they do occur often enough that Stony Brook has developed a practice to diagnose and treat them, which requires the support of experts in pathology. Stony Brook hired Dr. Fazel Khan a few years ago as the orthopedic surgeon to do this work.

“To establish a successful service, there needs to be a mechanism to financially support that service that’s not solely dependent on the number of cases provided,” Shroyer said.

Boyce’s recruitment was made possible by “investments from Stony Brook University Hospital and the School of Medicine, in addition to support from the Department of Orthopedics and Pathology.”

Shroyer was thrilled that Boyce brings not only his expertise but his deep and well-developed background to Stony Brook.

It was “important to me that he was not only a highly skilled surgical pathologist, but also was a physician scientist, which made him a very attractive recruit,” Shroyer said.

Indeed, while Boyce will provide pathology services to Stony Brook, he will continue to maintain a laboratory at the University of Rochester.

Boyce’s research is “focused on the molecular mechanisms that regulate the formation of osteoclasts and their activity,” Boyce said. He emphasizes the effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines and NF-Kappa B, which are transcription factors that relay cytokine signaling from the cell surface to the nucleus.

These factors drive osteoclast formation and activity in conditions affecting the skeleton, which include rheumatoid arthritis, postmenopausal and age-related osteoporosis and cancers affecting the skeleton.

Osteoclasts degrade bone, which carve out deformities or the equivalent of potholes in the bone, while osteoblasts help rebuild the bone, repaving the equivalent of the roads after the osteoclasts have cleared the path. There are over a million sites of bone remodeling in the normal human skeleton and the number of these increases in diseases.

Boyce has studied various aspects of how bone remodeling occurs and how it becomes disturbed in a variety of pathological settings by using animal models. He uses cellular and molecular biological techniques to answer these questions.

On behalf of Boyce and three other researchers, the University of Rochester Medical Center just finished licensing a compound to a company in China that he recently contacted, which will do animal studies that will test the toxicity of a treatment for myeloma.

At this point, Boyce is applying in July for another five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health for research in his Rochester lab. He hopes to renew another NIH grant next year, which he has for four years. After he renews that grant, he will continue writing up papers and studies with residents and collaborating on basic science at Stony Brook as well.

Boyce and his wife Ann, have three children and seven grandchildren. Originally from Scotland, Boyce has participated in Glasgow University Alumni activities in the United States, including in New York City, where he walked in this year’s Tartan Parade with his daughters and their children.

As for his work at Stony Brook, Boyce is enjoying the opportunity to contribute to the community.

“The setting and faculty are very nice and congenial and I’ve been made to feel welcome,” he said.