By Leah S. Dunaief

It’s difficult to live in the suburbs without a car. In fact, it’s almost impossible to raise a family here without four wheels. Many people own more than one to accommodate the various members of the household. And the costs of maintaining a car are escalating, threatening to take away from disposable income and the suburban quality of life.

Here are some statistics from a recent article in The New York Times that quotes the AAA.

The average annual cost in the first five years of ownership is now $12,182. Last year it was $10,728. This jump is a result of higher purchase prices, maintenance costs and greater finance charges. Just to put this in its proper perspective: “That’s 16 percent of the median household income before taxes.” And about 92 percent of households own at least one; 22 percent have at least three.

Here are some more facts. All those personal cars number some 223 million and together add up to trillions of dollars a year in spending. (I can’t even check this because my calculator doesn’t go up that high.) How much, by comparison, was spent on public transportation in 2019 for capital and operating expenses? The answer, while still up in the mind-blowing category, is only 79 billion. Just drop the zeros and you get the point.

Car expenses can be on a par with housing, child care and food for some families. The average payment for a used car is $533, according to TransUnion, while the average for a new one is $741 a month. Multiply that by the number of cars parked in one driveway for a household.

Some examples of car expenses: monthly payments, which have gone up in the last year, either to buy or lease, gas, registration, insurance, regular maintenance, perhaps tolls, parking, car washes and maybe even an un-budgeted accident. While insurance covers most of that, still there is deductible, perhaps loaner costs, not to mention the toll of stress and aggravation, which we are not even measuring with a price tag.

Now to the other side of the equation. Some people love their cars. They love driving them, washing them, caring for them, even naming them. They love shopping for them. They love proudly comparing theirs to other comparable vehicles in animated discussions with likeminded owners. Their car is a pleasure they don’t mind spending on because they get more from it than just passage from one point to another. For some, a car is like having another child.

Since I grew up in New York City, where public transportation is, for the most part, excellent, my parents never had a car. I remember when my dad made a careful list of the expenses connected with owning a car and decided we could take taxis all over town for much less. Of course, we never took taxis either. And neither of my parents had a driver’s license. My mother, who loved a bargain, was particularly delighted that one could take the subway for miles, from one borough to the next, even to Coney Island and Rockaway Beach from midtown Manhattan for only one 15-cent token. Having to travel in a car for her would have been a deprivation.

The other issue about cars, of course, is pollution. As we are thinking green, we are aware that automotive emissions are responsible for some 50 to 90 percent of air pollution in urban areas. Wherever they are, motor vehicles are a major contributor to air pollution.Those emissions affect global warming, smog and various health problems. They include particulate matter, carbon monoxide and nitrogen dioxide. All of those are toxic to living organisms and can cause damage to the brain, lungs, heart, bloodstream and respiratory systems—among other body parts.

All of that notwithstanding, it is said we have a love affair with our cars.

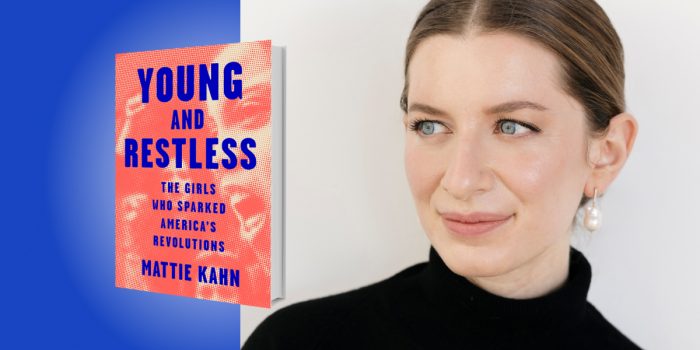

The book tells stories of many more such young women—girls really—protesting in different circumstances. “There’s Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, who led 17,000 people up New York City’s Fifth Avenue on horseback in the 1912 march for women’s suffrage.” Anna Elizabeth Dickenson was an abolitionist orator in her teens and became the first woman to address the House of Representatives. Heather Tobis (Booth) at 19, “founded the legendary abortion referral service Jane out of her dorm room. Clyde Marie Perry, 17, and Emma Jean Wilson, 14, integrated their Granada, Mississippi schools in 1966 and then successfully sued to stop expulsions of pregnant students like themselves.”

The book tells stories of many more such young women—girls really—protesting in different circumstances. “There’s Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, who led 17,000 people up New York City’s Fifth Avenue on horseback in the 1912 march for women’s suffrage.” Anna Elizabeth Dickenson was an abolitionist orator in her teens and became the first woman to address the House of Representatives. Heather Tobis (Booth) at 19, “founded the legendary abortion referral service Jane out of her dorm room. Clyde Marie Perry, 17, and Emma Jean Wilson, 14, integrated their Granada, Mississippi schools in 1966 and then successfully sued to stop expulsions of pregnant students like themselves.”